Worth 1,000 words

Updated: 2011-09-14 08:02

By Liu Xin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Elderly readers are attracted to xiaorenshu for a taste of nostalgia at a book reading festival in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, in April. [Wang Luxian / for China Daily] |

Picture books that were once all the rage have now become collectors' items, but new efforts are being made to make them mainstream once again. Liu Xin from China Features reports.

Reading palm-sized picture books, or, xiaorenshu, was a national pastime in China for decades in the 20th century, but only hardcore collectors and people hankering after a taste of nostalgia bother to read them anymore. Yet, those who do choose to peruse the shelves at an antique market outside of Beijing's Baoguosi Temple will be well rewarded for their efforts, although purchases there can be quite expensive.

It is not unusual for collectors to shell out as much as 400 yuan (about $62) for a single xiaorenshu; the same books used to go for just 2 jiao (10 jiao equals 1 yuan) more than 30 years ago. The most expensive volumes fetch more than 10,000 yuan apiece.

Lin Rongqiang, a 46-year- old businessman from Beijing, has more than 13,000 xiaorenshu in his private collection.

"In my childhood, I had few hobbies other than reading xiaorenshu," Lin recalls.

Lin's most recent purchase was a 700 yuan xiaorenshu that he bought to complete a series in his collection. When he began collecting in 1999, xiaorenshu could be purchased for just 1 yuan apiece. Speculators have since driven up prices.

"It's a shame that people resell them at a profit," Lin says. "These books used to be read by almost everyone. They are a vestige of Chinese history and culture."

Xiaorenshu consist of highly detailed panels accompanied by a text of about 90 Chinese characters. The books often depict the adventures and travails of historical figures, such as those shown in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and the Journey to the West series.

Jiang Weipu, an 85-year-old editor from Beijing, is currently working on a book about the decades that he has spent in the xiaorenshu publishing industry.

Born in Shandong province, Jiang was a war correspondent in his 20s. In 1953, he came to Beijing to work for the People's Fine Arts Publishing House, where he served as an editor until his retirement.

Jiang says xiaorenshu played a significant role in mobilizing the masses, and in shaping public attitudes and opinions, particularly during the 1950s and the 60s.

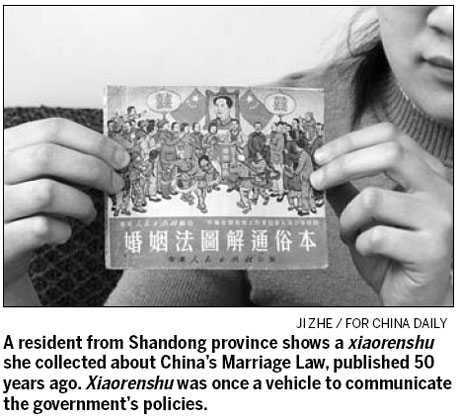

Between 1925 and 1945, xiaorenshu dealing with the theme of land reform, as well as China's battle against the invading Japanese, were published in areas that had been liberated by the Communist Party of China (CPC). "Xiaorenshu was then a vehicle to communicate the government's policies," Jiang says.

Xiaorenshu continued to enjoy a "golden age" of sorts, thanks to late Chairman Mao Zedong who employed it to encourage people to support the CPC's practices and policies. For this very reason, more than 260 million xiaorenshu were published between 1951 and 1956, Jiang says.

Shi Hang, a playwright born in 1971, recalls the good old days when he enjoyed reading xiaorenshu. "Undoubtedly, xiaorenshu widened my horizons when I had limited sources to learn about the world during my childhood in my hometown in northeast Jilin province," Shi says.

"And foreign stories in xiaorenshu led me to exotic countries. It felt great."

However, the industry soon took a plunge with the arrival of the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976). Few xiaorenshu were published between 1966 and 1969.

Fortunately, the books saw a revival under then premier Zhou Enlai, who believed that xiaorenshu should be published in greater numbers to encourage younger generations to be more culturally literate.

As a result, more than 860 million xiaorenshu were published in 1982, setting a record for the number of xiaorenshu published in a single year. Many of the books even came with English versions for overseas markets.

The xiaorenshu industry took an unpredicted turn around the mid-1980s, when Japanese picture books started becoming popular in China as a result of the country's reform and opening-up.

Youngsters gravitated toward the flashy art and innovative plotlines of the Japanese picture books, giving the Chinese xiaorenshu industry a blow from which it has never quite recovered.

When asked whether children still have any interest in reading Chinese xiaorenshu, Lin, the Beijing businessman, says, "Few people read them now. Even for us, they are just collectors' items."

For his part, Jiang, the editor, tried to use Japanese picture books as an impetus to encourage innovation and renewal in the Chinese xiaorenshu industry. As a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in 1994, he took 30 volumes of Japanese picture books to other members to stress their readability.

"Japanese picture books had attractive plots, which could have been used in our own xiaorenshu," Jiang says.

One factor that has led to the decline of Chinese xiaorenshu is the lack of qualified illustrators. The detailed panels and unusual visual angles present in picture books require illustrators to possess a wide variety of skills. China's last school dedicated to cultivating talented illustrators closed in the early 90s. These days, there are fewer than 100 qualified picture book artists in China.

"Young painters prefer to master a single skill, as it is easier for them to make a living by specializing in one area," Jiang says. "None of them bother learning the variety of skills necessary to become a qualified picture book illustrator."

Another contributing factor is the way the books are published. According to Jiang, publishing houses were required to stick to specific series and topics during the golden age of China's picture books industry.

"Only the Shanghai People's Fine Arts Publishing House was allowed to publish Romance of the Three Kingdoms, while the Hebei Fine Arts Publishing House published Journey to the West," Jiang says.

These requirements are long gone, and publishing houses are now free to publish xiaorenshu of their choice. However, this has led most of them to publish outdated or redundant versions, as this is cheaper than hiring writers and illustrators to turn out new works of art. "Their quality cannot be guaranteed at all," Jiang complains.

The 60-volume Romance of the Three Kingdoms series currently sells for 999 yuan.

Modern forms of entertainment have also served to weaken the influence and spread of Chinese picture books.

Jiang says he has been thinking long and hard about how to resurrect Chinese picture books that can fit into modern society. Around the end of last year, he submitted a report to the Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee, proposing the republishing of classic works to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the CPC's founding.

Jiang has asked the publishers to distribute these xiaorenshu in rural areas. "When parents move to big cities as migrant workers, their children can have something to read," Jiang says.

He also writes articles for industry periodicals, encouraging editors, illustrators and other xiaorenshu industry professionals to remain steadfast in their efforts. "I only hope that xiaorenshu can resume its social role, besides collection," he says.