Small angle, wide view

Updated: 2014-02-18 07:17

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Writer Wang Anyi finds the drama of life in its fine details as she examines social changes, she tells Mei Jia.

In a quiet corner in the heart of downtown Shanghai, a handsome young man with a stutter reaches a tacit friendship with an elderly button-shop owner, who finds it difficult to speak long sentences after a stroke and has opened the shop to sustain himself and kill time.

Both struggle to get others to understand them, but they come to know each others' hearts through simple words.

|

Shanghai-based author Wang Anyi has many of her novels, including her latest book, set in the city which has nurtured her writing throughout her career. Provided to China Daily |

"It's rather impossible," the old man would say. For sentences longer than that, he would stammer. So he has developed economy in his daily speech.

"So it is yah," the young man with a handsome face would reply, in the local Shanghai accent.

They get along peacefully until one day a pretty woman, from the country's northeast, gets between them. She talks fast - lies, mostly - and the vulgar lady sells cheap clothes with trickery, renting a small corner in the old man's house.

The young man has a crush on her, though she is married.

Focusing on the everyday people living in the margin of the metropolis, writer Wang Anyi pays tribute to the country and its huge social transformation, cutting only a slice from the hustle of city life.

Critics believe Wang has found a unique way to depict the small eddies of human emotion caused by the changes in Chinese society as cities get more commercialized.

"Wang seems to find the key to record urban Chinese experiences: Using a small angle to reveal the bigger picture," says fellow writer Zhao Yu. "It's so far the best novella I have read in the past few years."

"The old man and the different arrangements of his house for his children is an epitome of Shanghai's recent development. While the young man represents the ordinary people at the city's bottom, the woman represents the migrant workers," Zhao adds.

The novella, along with six other short stories, is included in Wang's latest book Zhong Sheng Xuan Hua (The Noisy Life), after she finished her longer work Scent of Heaven.

Penguin is set to publish an English edition of Scent of Heaven later this year, believing Wang's writing "tends to focus on local details and the private rather than public sphere".

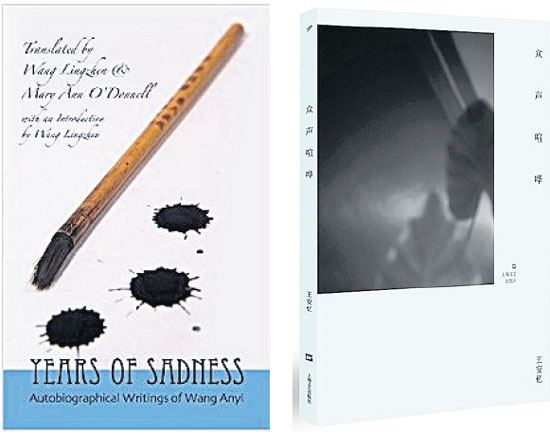

Nominated for the 2011 Man Booker International Prize and winner of the country's prestigious Mao Dun Literature Prize, Wang was hailed as "the most prolific and critically acclaimed woman writer in contemporary China" when Cornell published her Years of Sadness: Autobiographical Writings of Wang Anyi.

Carmen Callil, when judging the Man Booker prize, said Wang "is such a great writer it was easy to see her worth despite some rather bad American translations".

Wang is known for her novel The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, which some said connected her with "nostalgic" writers. But she denies that, saying "I'm a strict realistic writer and I write about the society at the moment".

She also denies being a "feminist writer", though she writes a lot about women, saying it's too easy to put such labels on writers.

The most prominent tag on her is "Shanghai", the setting of many of her works. Born in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, in 1954, Wang moved to Shanghai the next year with her mother Ru Zhijuan, also a well-known writer. Since then, the city has nurtured her writing talent - she has been publishing since the late 1970s, and she still lives and works in the city.

"My relationship with Shanghai is actually full of tension. I don't like the place, but I can't avoid it. I know it so well that I don't have another option," Wang says.

Wang, who enjoys writing because of the power of imagination, creates characters with compelling traits and values that - because of social changes, she says - can most easily be found among the marginalized groups.

"Because their problems, like the speaking obstacles of the young and old men in the novella, make it possible for them to avoid the overwhelming influences from the so-called mainstream thinking and attitude," Wang says.

Wang says she never wastes time in unnecessary characters in her works.

"Everyone has a mission," she says, adding her writing starts with setting tones for the characters.

Literary critic Chen Sihe says Wang's novella depicts humane concern in a time of transformation. She can be encouraging about change, "while keeping a vigilant and sober mind on the possible pain it brought about", Chen says.

"In a time like this, I welcome changes, and I have changed, too," Wang says. "But I want to remind people about the value of the unchanged, like the power of literature, and the faith in literature."

Wang says she's lucky to have gained a foothold before the society became too commercialized.

"So that I can publish the six short stories along with the novella. A debut writer would get rejected if they presented those stories," Wang says.

The six short stories, as she insists on calling them, are actually philosophical thinking without a human character. They are experimental and have prompted debate.

"I impersonate objects in the stories. They have plots, suspension and answers for suspension," she says.

It's not her first experiment with words.

"Attempting to be different, I wrote things that I find difficult to read, too, in the 1980s," she says.

Wang was rebellious because her writer mother hoped she would not take on "those pains of being a writer", Wang once said.

"And she seldom praised my writing," she added.

In the 1980s, Wang went to the US-based Iowa International Writing Center for a creative-writing workshop with her mother.

"As I return to the essential of writing, the storytelling, I have realized I also get a lot of inspiration from my mother's writing," Wang says.

Currently dividing her life among writing, reading and teaching, Wang is a professor of creative writing at Fudan University. Her workshop is popular among the students.

She believes young writers often follow blindly the "popular social implications" they get from easy reads.

"They don't know what to write about," she adds.

Though she feels regret when a student fails to get excited upon reading one beautiful sentence, like she does, Wang holds that the current ecosystem of Chinese literature is in good shape.

"We don't lag behind the 1980s, the golden era of literature, too much. Writers are still writing as well, seriously and diligently," she says.

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Some of Wang's works have been translated into English, such as Years of Sadness published by Cornell. Her latest book Zhong Sheng Xuan Hua (right) arouses great interest in China. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 02/18/2014 page22)

Gorgeous Liu Tao poses for COSMO magazine

Gorgeous Liu Tao poses for COSMO magazine

Post-baby Duchess

Post-baby Duchess

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Envoy begins four-day visit to DPRK

Hainan boosts tourism to Xisha

Policeman gets death sentence for shooting

Woman claims legislator is her child's father

Beijing calls on Tokyo to return plutonium to US

Xi calls on leaders to carry out new reforms

Trade inquiry creates friction

Bigger Chinese role in the Arctic

US Weekly

|

|