Business

Health warning over joint cooperation

By Karen Yip (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-29 08:12

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

|

|

Public and private hospitals face challenges working together

BEIJING - The inside joke at Huashan Hospital Pudong is that it takes two months to acquire toilet paper, when the need arises.

This is what a team consisting of international and local doctors, nurses, marketing executives and managers from United Family Hospital (UFH) discovered when they were put to work in the establishment's international wing.

To say it is upsetting the Chinese people is an understatement. Certain well-informed government officials and certain individuals on the board of directors of the 103-year-old public hospital were beyond frustration.

To add insult to injury, the hospital, which is equipped with expensive, sophisticated medical equipment and facilities, is not fully utilized to its capacity. It also suffers from poor quality treatment and service, says insiders.

Not only does it speak volumes on how a Chinese public hospital functions, but it also indicates it will not be smooth sailing especially for foreign-owned hospitals that attempt to work together with Chinese public hospitals.

In addition, questions over profitability and the social responsibility of public hospitals often invite heated debates - be it objective or one-sided arguments - from all quarters.

As part of a pilot project to encourage reform at public hospitals, the Shanghai local government invited foreign-owned UFH - which owns a group of private, premium hospitals across China - to partner with Huashan Hospital and Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Ltd, a listed company that invests in pharmacy, clinical diagnostic, and therapeutic products.

The partnership, sealed in April 2010, was a strategy to transform Huashan Hospital into adopting an international approach, an initiative under the country's healthcare reform efforts where public hospitals make up one of the most important components of the reform.

"It has been difficult for everyone when there's a rigid process in an entrenched 100-year-old public hospital. Our folks learned a lot from them," Roberta Lipson, UFH's chairwoman, said during an interview with China Daily, after reflecting on the seven-month working relationship with Huashan Hospital.

"When you have different corporate cultures and mentality working side-by-side, it's going to create friction. However, we see opportunities in the public-private hospital model," she said.

These are mergers and acquisitions, partnerships, and joint ventures between private, foreign-owned hospitals and Chinese public hospitals.

When asked what are her plans for the partnership, she said: "We (UFH) plan to continue to expand our services to include inpatient and surgeries."

It's only been a couple of months into the Huashan Hospital-UFH-Fosun Pharma partnership but progress is starting to show. For example, Huashan Hospital has started to offer pediatric services, similar to those offered by UFH.

"People are beginning to understand and are taking time to buy into the changes," Lipson from UFH said.

"If you can muddle through the frustration, then it's a win-win for public and private hospitals."

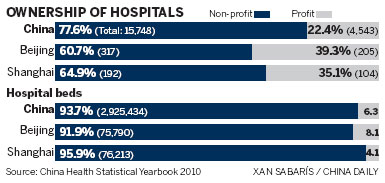

As part of the reform effort, the government is supportive of investment structures between private and public hospitals. A 10-year-old law allows foreigners to own up to a 70 percent equity stake in Chinese public hospitals.

However, Professor Li Ling, deputy director of the China Center for Economics Research at Peking University, has different views.

"You cannot divide dividends to shareholders. There is no such thing in the public hospitals. How can we be answerable to 1.3 billion people who need healthcare?" she asked China Daily when contacted.

On a daily basis, China's largest public hospitals handle 10,000 outpatients, she said. It is impossible for Chinese doctors to spend 15 to 30 minutes consulting a patient unlike the private hospitals where service is of the utmost importance.

"Internationally, it's all about service at the hospitals. In China, it's about disease prevention. With thousands of people cramming into the public hospitals on a daily basis, a Chinese doctor has only five to 10 minutes with a patient," said He Jingbin, director of government relations (China) at International SOS, a leading healthcare and security assistance group.

"There is no time to feel the patient. It's a social issue, not a medical competence issue," he said.

Li, who serves as a senior adviser for China's Ministry of Health, is also a consultant for healthcare reform at the World Bank. She drafted the Peking University health reform proposal, which was among the 10 proposals from universities and industry players solicited by the government.

When asked to comment on the opportunities offered by the government to encourage private participation in the public hospitals, she said: "It's not in a right direction. In the long-run, public hospitals will play a major role while the private hospitals will play a complementary role."

It is estimated that there are 700 million rural residents who don't have proper access to healthcare, said David E. Wood, managing director - Healthcare, at PricewaterhouseCoopers, Beijing.

"There's a saying in China that when a rural resident has to seek medical attention for an illness, his or her income for one year will be wiped out, even if that person has public insurance coverage."

In a statement on Sept 28, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) said it would release a set of guidelines for the healthcare sector at the end of October.

Private capital is expected to find its way into hospitals. Private medical institutions can apply to be part of the nation's medical insurance system, and their employees will be provided training and welfare just as in government-controlled institutions, the NDRC said.

Major issues of reform at Chinese public hospitals include establishing corporate governance structures, improving operations and service quality improvement and encouraging private capital investment in healthcare.

However, it is an uphill task for the public-private model to be accepted by those involved, especially when warring factions exist in the hospitals and at government-level.

"Certain individuals who wanted to maintain 'face' or power have tried to prolong the decision-making process or they spread rumors to create doubt," said a marketing manager who requested anonymity. He's currently involved in a public-private hospital.

"Sometimes it boils down to petty things such as replacing our logo from the reception area with their own. Only this time, they made a bigger one and put it at the entrance!"

While it is difficult to tell at the moment whether the public-private model is a success, there is a glimmer of hope. Take, for example, the joint venture between International SOS and the Red Cross Society of China.

Thanks to the understanding International SOS has of local conditions coupled with years of international experience, it has yielded positive results for International SOS clinics in Beijing, Tianjin, Nanjing and Shenzen.

International SOS and the Beijing chapter of the Red Cross Society of China have recently agreed to extend their joint venture - first sealed in 1994 - for another 15 years until 2025.

"We're happy with the joint ventures (in Beijing, Tianjin, Nanjing and Shenzhen). Both teams can sit down and discuss openly the issues at work. It's like fitting the puzzle together," He Jingbin of International SOS told China Daily.

The joint venture works in a unique way: While International SOS is in charge of business development, the local chapters of the Red Cross Society of China work on smoothing government relations and handling the hiring and management of local staff.

"We found that such segregation of work helps to reduce conflict. Our Chinese counterparts respect and trust us. We also complement each other - we bring corporate clients into the partnership," He said.

That was not the case with the $4.13 million SK Hospital in Beijing. SK - the Korean conglomerate with interests in telecommunications, energy, chemicals, construction and shipping - ventured into China's healthcare sector with the establishment of SK Hospital in 2003.

By the sixth year, the Koreans decided it was time to leave - without fulfilling their initial plans to open 20 hospitals in major Chinese cities, a forecast based on the tremendous opportunities in the private hospital sector.

In January 2009, the hospital was sold at a discount to EverCare Medical Institute, a Chinese-owned joint venture company that owns a chain of hospitals specializing in cosmetic surgery across China.

What went wrong?

"The management team, the experts, and the equipment were sent from SK and South Korea. The problem was that the management team didn't have any medical or healthcare experience. When there were problems, the team didn't know what to do," said Park Se-hyun, a former employee of SK Hospital, who is now on part-time employment as a medical consultant for the international department at EverCare Beijing Aikang Hospital, a reflection of the change in ownership and new direction.

"The new owners seem to know what they are doing," Park said. "Business is brisk. Most of the customers arrive in big, expensive cars and end up ringing the cash register with a four- to five-figure expense receipt for a visit."

China Daily