Checkmate, Mongolian style

Updated: 2013-07-02 06:19

By Wang Kaihao and Yang Fang in Abag Banner, Inner Mongolia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

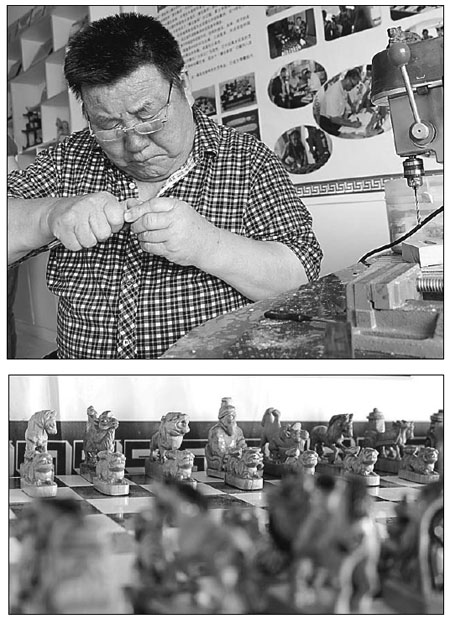

Top: Norbu, 60, works on a Mongolian chess piece called shatar, an intangible cultural heritage of the Inner Mongolian autonomous region. Above: A shatar set made by Norbu. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

It is like chess, but this Mongolian cousin of the Western board game is different.

Norbu wears presbyopic glasses and stares at a tiny piece of wood. Beads of sweat ooze from his forehead when he focuses on carving the wood.

The 60-year-old ethnic Mongolian says he has been emotionally attached to the small pieces of wood since childhood.

"I was not allowed to touch the chess pieces when I was a child. The adults were afraid I would break these treasures," he recalls. "The shatar sets were antiques passed down through the generations because not many people knew how to make new ones."

But Norbu's eagerness to play shatar motivated him to try to make his own set, and he proved good at it. With a knife and a drill, what started off as hobby became an adventure of promoting the age-old tradition.

Shatar has ambiguous roots in the 13th century and is generally believed to derive from shatranj, a Persian game, which is also the embryo of modern chess. Shatar still keeps some of the original rules of shatranj. What distinguishes shatar from other chess variants are its chess pieces and slightly different rules.

Queens in shatar are shaped like lions or tigers. Bishops are replaced by camels. Pawns are carved into hounds while rooks look like carts.

"These are reflections of lives on grasslands," Norbu explains. "But there is no uniform shape for each piece. I can thus create a diverse variety of chessmen."

He says each handmade piece is unique because of the details, adding that he does not draw a blueprint before carving. Instead, he lets his imagination fly.

"Being a carver, I have to have brilliant eyesight. Details are of extreme importance. If I don't seek perfection, the shatar pieces will look rough, like those easily found in the market."

He sources his wood from old furniture because the price of some luxurious timber like red sandalwood is too expensive.

A set of handmade shatar will take more than two weeks to finish. He is overjoyed to find many collectors who are willing to spend more than 20,000 yuan ($3,200) per set.

Norbu has attended numerous exhibitions around the country. Certificates of honor from the 1980s fill two big plastic bags. His handmade shatar were listed as Inner Mongolia's intangible cultural heritage in 2010 and he is now applying for the national-level.

Norbu does not speak English, and his Mandarin is poor. But he says language is no barrier to spreading the tradition of shatar. He cited his experience representing Inner Mongolia at exhibitions during the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008 and the Shanghai Expo in 2010.

"When foreigners saw the shatar set at my booth, they sat down and played chess with me without saying a word. I am glad the small pieces are able to draw international attention. To promote the tradition, I gave them pieces as gifts," says Norbu.

Although he believes in creativity of the chess pieces, he is a stickler for authenticity and traditional styles. For example, he says it is a bad idea to add a round base to the pieces because that will make them look too similar to modern chess.

Like other inheritors of handcrafts skills, his major concern is to get more young people involved in reviving the Mongolian tradition. He has recruited two apprentices but is disappointed that few youngsters have patience for the craft.

His dream is to open a school to stop handmade shatar from disappearing. He has written to the local government to request funding.

Norbu also finds time to coach children to play shatar and teach an elective course in Inner Mongolia Normal University in the autonomous region's capital Hohhot to promote the game. He believes that to preserve the tradition, he needs to promote it among the young.

"But, I'm not interested in large-scale production," he says, adding that he feels comfortable using simple tools and working in his small studio. Although he is active on WeChat, a mobile text and voice messaging communication service, and Tencent QQ, a popular free instant messaging computer program, he admits to being behind the times when it comes to modern technology.

"I won't be able to handle the huge demand if I sell them online. The quality will inevitably decrease if shatar is produced in large amounts. Promotion of heritage is more important than making money," he adds.

Contact the writers through

wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 07/02/2013 page10)

Egypt army gives Mursi 48 hours to share power

Egypt army gives Mursi 48 hours to share power

No quick end in sight for Beijing smog

No quick end in sight for Beijing smog

New filial law sparks debate

New filial law sparks debate

Bakelants claims Tour de France second stage

Bakelants claims Tour de France second stage

2013 BET Awards in Los Angeles

2013 BET Awards in Los Angeles

Gay pride parade around the world

Gay pride parade around the world

Four dead in Egypt clashes, scores wounded

Four dead in Egypt clashes, scores wounded

New NSA spying allegations rile European allies

New NSA spying allegations rile European allies

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Kerry hails China's denuclearization bid

19 firefighters killed in Arizona fire

Book reveals islands' true history

Tokyo warned not to resort to 'empty talk'

Snowden applies for Russian asylum

No quick end in sight for Beijing smog

New home prices defy curbs

Mandela 'still critical but stable'

US Weekly

|

|