Setting Mao in stone

Updated: 2013-07-16 07:14

By Li Yang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

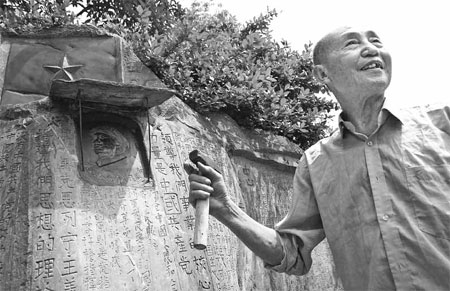

Jiang Jiwei shows his works featuring Chairman Mao's quotations at Yulu Hill, in 2008, in Zhutang village of Quanzhou county, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Photos by Huo Yan / China Daily |

|

Liu Xiaoying, Jiang Jiwei's wife, introduces her husband's works at the foot of Yulu Hill in Zhutang village. |

|

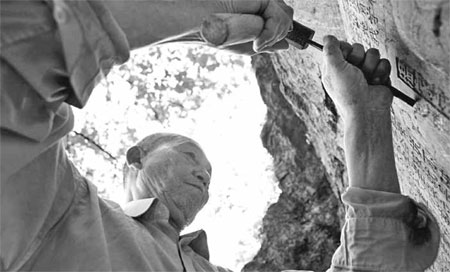

Jiang Jiwei carved daily before passing away in 2009. |

Overcoming severe hardships, a local eccentric created stone monuments that continue to inspire visitors. Li Yang reports in Guilin, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

Jiang Jiwei was a farmer before he was 35 years old, the "enemy of the people" during the first four years of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and a rock carver afterwards till his death in 2009 at 78 in Zhutang village, Quanzhou county of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

"He had always been Chairman Mao's student all his life," says his illiterate widow, 82-year-old Liu Xiaoying.

The hill behind their shabby house is called Yulu Hill, or a hill of Chairman Mao's quotations, because half of the southern slope of the small hill is carved with the words of Mao and the other Chinese leaders' quotations and their portraits.

Jiang started carving on the hill in 1970 and continued until he did not have the strength to lift a chisel in 2008. He left behind 70 portraits - embossment and statues - of famous communists in China and about 220,000 characters of 1,200 pieces of quotations of the people.

"It is said he feigned madness and acted like an idiot to protect himself from the radical revolutionaries' persecution," says Jiang Caizheng, 83, a fellow villager who knows Jiang Jiwei well. "He was simply immersed in the hard work of carving and did not care about anybody else."

Born in a farmer's family, Jiang Jiwei was educated for three years in a family school. He was a clever farmer and a skillful self-taught carpenter with some knowledge of Chinese traditional medicine.

He was warmhearted and always ready to help other villagers, according to his wife. "I married him because of his kindness and brightness, despite his poor family," says Liu Xiaoying, who was acclaimed as the most beautiful woman in the village decades ago.

Wang Zichuang, a local reporter from Guilin who interviewed Jiang many times, says, Jiang believed in communism and applied to join local pro-Communist guerrilla forces during the civil war (1946-49). He was refused because he did not have a gun.

An anonymous female villager and neighbor of Jiang says he was wrongly classified as "rich farmer" in the "cultural revolution" just because he lent a kilogram of grain to his poor neighbors in the early 1960s.

Jiang refused to accept the title, which meant he would become an "enemy of the people". But the Red Guards intimidated him: If he did not follow orders, his title would be upgraded to "landlord", a criminal title that could lead to a death sentence at that time.

"Ten landlords were executed by shooting and he was forced to see the execution at a close distance and ordered to carry and bury the bodies," Jiang Caizheng says. "The killing scared him out of his wits and he became another person ever since. He did not talk about anything else, except Chairman Mao's quotations, from then on."

His wife was molested by a village head, the last straw that broke his nerve. He tried to kill himself many times with carpentry tools in 1970. One day, he gave up the suicide plan and quietly became a vegetarian and a Christian, Jiang Caizheng adds.

A Christian cross made by himself was hung in the wall of his "cell", which could only hold two single beds. On the muddy ground were piles of his old chisels and hammers; he refused to use modern electronic tools to carve the rock.

He carved portraits of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Karl Marx and Zhou Enlai, and memorialized Mao's quotations. He could recite almost all quotations of Mao accurately, with emotion.

"Nobody taught him how to carve and he could only carve five Chinese characters per day at first. He seemed to forget the world when he took up the chisel," Liu Xiaoying says. "Our two sons and one daughter put one bowl of rice noodles with pickled peppers and a glass of liquor in front of his door each day. That's all he had every day from 1970 to his last few days."

Jiang Caihui, Jiang Jiwei's younger son, says: "My father was very stubborn and never went to see a doctor when he felt ill. He thought he could survive all diseases and have a long life by reciting Mao's quotations and paying loyal tribute to Mao."

Jiang Jiwei carved some cups out of the rock in front of the revolutionary heroes' relief portraits. Each morning after getting up, he rushed to fill the cups with water and bowed in front of each statue three times before starting his day's work, as though the great ones would be angry with him if he did not go through the ritual quickly.

Jiang Jiwei welcomed young people to see his works and he hoped they could learn from Mao's thoughts. He demanded that all visitors write their names and feelings in his notebook.

In an interview with local newspapers, Jiang Jiwei confessed: "The people I carved are great for their bravery, brightness, loyalty, honesty and integrity. Although I was abused before, I love Chairman Mao from the bottom of my heart."

He only left the village twice after 1970. Once was to buy spectacles in 1990. He marveled at the big changes of times when he reached the county. The other time was to buy a shirt in 2001, when he was invited to give a TV interview.

Jiang Yanjiao, a former town head accompanying him then, says: "He always murmured to me that the Party's cadres are not as atrocious as before."

He felt his hard work paid off when he saw people become emotional when they came to see his carvings, Jiang Yanjiao adds. "He always told me Mao is a great man and his quotations are also useful for today's people."

Jiang Jiwei was buried on the hill after he was found dead in his bed, accompanied by Mao's statue.

One visitor wrote in Jiang Jiwei's notebook: "The world mocks his insanity. He derides the world's stupidity in return."

Contact the writer at liyang@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 07/16/2013 page10)

Obama urges restraint amid protests

Obama urges restraint amid protests

Putin wants Snowden to go, but asylum not ruled out

Putin wants Snowden to go, but asylum not ruled out

Apple to probe death of Chinese using charging iPhone

Apple to probe death of Chinese using charging iPhone

Investment falters as industrial activity flags

Investment falters as industrial activity flags

Rape victim's mother wins appeal

Rape victim's mother wins appeal

Reproduction of 'Sunflowers' displayed in HK

Reproduction of 'Sunflowers' displayed in HK

Land Rover enthusiasts tour the world

Land Rover enthusiasts tour the world

US star sprinter fails drug test

US star sprinter fails drug test

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Spain apologizes to Bolivia for plane delay

International cotton contract in the works

Smithfield shareholder still presses for break up

China calls for new talks on Iran nuclear issue

Global warming may largely raises sea level

Putin wants Snowden to go, asylum not ruled out

US: China can balance own growth

Top foreign study destinations for Chinese

US Weekly

|

|