Weaving clouds of color

Updated: 2013-07-22 08:21

By Li Yao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

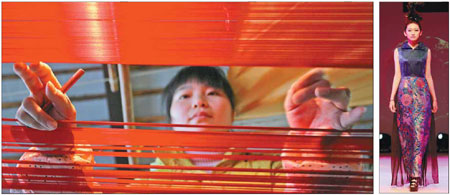

The age-old craftsmanship of brocade weaving still thrives, thanks to the dedicated artisans with the Nanjing Brocade Research Institute. Traditional brocade takes on a modern look at a Nanjing fashion show. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

Cai Xiangyang, once a law graduate, is an apprentice to a master artisan in Nanjing Brocade Research Institute. Provided to China Daily |

|

Operating each loom requires two people with great patience and skill. Li Yao / China Daily |

Highly skilled workers employ traditional techniques to create brocades once worn by emperors. Li Yao reports.

Nanjing was the ancient capital of six dynasties in China, and in August, it will come under the limelight again as the host city of the 2nd Asian Youth Games. Its rich history and cultural heritage are sure to impress first-time visitors.

There are many traditional crafts still preserved in this historic destination.

Weavers in the city today are still making Nanjing cloud-patterned brocade, considered the most extravagant silk fabric that was produced exclusively for emperors and imperial court officials.

It was called yunjin or cloud-patterned brocade because its woven motifs were as beautiful and diverse as clouds in the sky.

The techniques of weaving this brocade have a history of more than 1,500 years. They were, however, almost on the brink of extinction until 1979 when the Nanjing Brocade Research Institute tried to replicate a dragon robe that had been unearthed from one of the Ming Tombs in Beijing.

The robe was in tatters and its brilliant colors were fading from exposure to air. Researchers concluded that it had been made in 1619 during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). This was the period when the cloud-patterned brocade production was at its peak and private workshops were allowed to develop because of rising demands from the imperial court.

It took specialists five years to resuscitate the ancient skills and recreate the brilliant luster and colors of this historic robe.

The design features dragons and symbols of longevity such as cranes, and it was embroidered with gold thread and peacock feathers.

One major hurdle was finding the appropriate loom.

Zhou Shuangxi, the youngest member of the restoration team, explains that they found two looms at one household and had them resembled, but they were very worn out and the wooden parts had become moldy.

A yunjin loom is a large and complicated piece of machinery. It measures 5.6 meters long, 1.4 meters wide and 4 meters high, and is made up of 1,924 small components. It is manually operated by two weavers and involves a distinctive technique to make the jacquard patterns.

This is a weaving process that dates back to the 1700s, named after its French inventor, Joseph Marie Jacquard. Jacquard weaving cannot be done on modern machines.

Zhou, now 58, has since seen more masterpieces replicated from excavated brocade items. He was named the chief intangible cultural heritage craftsman after yunjin was inscribed by UNESCO on its representative list in September 2009.

UNESCO's record of intangible heritage crafts was created to demonstrate the diversity of such heritage and to raise awareness of their importance. Other skills from China on the list include calligraphy and shadow puppetry.

A broad range of skills and knowledge are required from the weavers, as Zhou explains.

"I need to know everything about brocade making," he says. "From assembling the loom, dyeing silk threads with natural dyes, designing the patterns and drawing the blueprint, loading the loom with thread and lining up the warps, to the final weaving."

Zhou says great patience and meticulous care is required.

The weaver handles the shuttle and pedals on the loom's footboards, and keeps in mind how to arrange the colors. Creating the brocade is a slow and intricate process requiring considerable attention to detail.

An experienced craftsman can weave about five centimeters in one day at most. If the weaver has finished one piece of brocade and move to a new pattern, the loom has to be reloaded and readjusted.

Zhou's fascination with brocade making was not love at first sight.

As a high school graduate he was assigned to the weaving workshop, and was concerned that he would be looked down on for doing a woman's job. Job-hopping was unheard of at that time, and carried little appeal because the salaries of different jobs were almost all the same.

"The old weavers were all men; illiterate and poor. They learned the weaving formulas by heart," Zhou says.

He acknowledges that work conditions for the weavers have improved greatly.

"In the old days, weavers endured hot summers and freezing winters. There was no air conditioning. They could neither use electric fans in summer nor build a fire to keep warm in winter, for fear that the threads would get knotted up or get burnt," Zhou says.

His confidence was boosted during exhibitions abroad, where the audience showed deep interest and respect for the skills of the weavers. Zhou left one loom each in Belgium and Norway, at the request of locals who offered to keep the apparatus and arrange further exhibitions.

Zhou's main responsibility now is to train more young people although he says reliable and committed apprentices are in short supply.

He understands that young people today face more distractions and pressure to climb the social ladder and make money, rather than throw their college degree away and start all over again to learn the basics of weaving.

"College degrees are almost irrelevant in learning the weaving techniques," he says. "Many young graduates came to me with high expectations and soon found the job was boring, and no match for their degrees. I have seen many leave after a few months or a year, to look for better-paying jobs."

Cai Xiangyang, 33, is Zhou's favorite trainee and the only apprentice that Zhou recognizes.

Cai had a bachelor's degree in law when he joined the Nanjing Brocade Research Institute in 2004. He later completed a master's degree in intangible cultural heritage protection.

Cai's persistence and diligence have won the trust of the institute officials.

"I can sit at a loom for 10 hours a day, and I keep practicing through Saturdays and Sundays. The job calls for scrupulous attention and the ability to resist distractions and loneliness," he says.

Cai has followed Zhou's steps and hopes to succeed Zhou as the inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage one day.

"For Master Zhou's generation, their job has focused on preserving the traditions and repeating the conventional patterns, such as dragon, phoenix and peony flowers," Cai says. "The ambition of the younger generation is to master the ancient skills and experiment with new ideas, to make these formerly exclusive dresses accessible to the public."

Today, the brocade is used in home textile products, wedding gowns, scarves, and cushions, folding screens and framed artworks.

Cai says the brocade museum will give guided tours to young athletes taking part in the Asian Youth Games in August. They will be invited to have a try at making silk thread from a cocoon, dyeing the threads and operating the loom.

Hu Delong, 49, has 30 years' experience weaving cloud-patterned brocade. At the institute, weavers are paid by finished pieces and many weavers are husband and wife, or sisters and brothers, pairing up as a team. It takes three to five years to finish training.

Hu, his wife, and his sisters-in-law, are all weavers.

He says he earns at most 6,000 yuan ($972) a month, and sometimes only 3,000 yuan a month. He works at the exhibition hall at the institute, demonstrating the weaving techniques to visitors and answering their questions.

Hu does not intend to introduce his only daughter to the business, because young people often struggle to cope with the boredom and demanding workload of the job. Hu himself has developed a true passion for the handicraft and plans to work until he is 60.

He takes pride in the fact that his masterpieces are recognized by television presenters during Spring Festival galas, exhibited in international sporting events, and purchased as souvenirs.

"There can be endless variations in using different colored thread to make a given pattern. It demands ingenious intuition rather than merely memorizing the weaving procedures," Hu concludes.

Contact the writer at liyao@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 07/22/2013 page9)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live Report: 47 dead, 296 injured in earthquake

Hard landing of China economy no topic at G20

US Navy drops bombs on Australia's reef

Woman jailed in Dubai after reporting rape

Guangdong to probe airport bomber's allegations

Police meets GSK representative after scandal

US protests demand 'justice for Trayvon'

Chinese admiral to visit the US

US Weekly

|

|