Lurking threat

Updated: 2013-07-24 07:21

By Liu Zhihua (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Vaccinations and regular health checks are effective ways to prevent hepatitis B infection. Photos Provided to China Daily |

It can take years for a hepatitis B infection to turn into cirrhosis of the liver and even cancer, and the lack of early symptoms means people are far too complacent, experts tell Liu Zhihua.

In September 2011, Liu Junjie had just enrolled in Hefei University of Technology for a master's degree in computer science.

A few days later, the happy and confident 23-year-old was sent to a hospital because of sudden and fierce abdominal pain, and was diagnosed of end-stage liver cancer.

Doctors said his liver cancer developed from a hepatitis B infection.

Liu's infection was detected in 2006, but due to his family's financial restraints and ignorance of the disease, he seldom took anti-virus medication and did not have regular checkups before 2011.

Liu died early this year, and his case is far from unique.

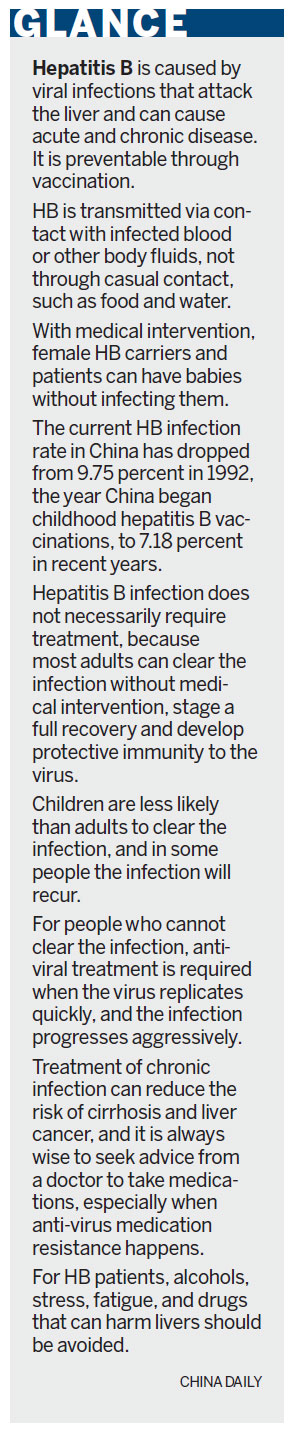

Hepatitis B, an infectious inflammatory illness of the liver caused by the HB virus, is endemic in China.

According to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the country has about 93 million people infected with the virus, and about 70 percent of them are chronic carriers.

The incidence rate of HB infection in China has dropped dramatically in recent decades, thanks to the national program of HB vaccination among children and adults.

But as World Hepatitis Day approaches on July 28, experts warn that HB patients are still not well-informed about the disease, and many overlook its serious threat.

"The greatest health risk of HB is to cause long-term liver diseases, including cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, and liver cancer," says Xiu Dianrong, a liver-disease specialist and surgeon at Peking University's No 3 Hospital.

"But many people are not aware of this, and do not intervene to prevent the disease from progressing." One problem: Early-stage liver cancer usually has no symptoms.

Pain comes too late

Nearly half of liver-cancer patients in the world are in China, and about 80 percent of them are associated with HB, Xiu notes. It usually takes five to 10 years for an HB patient to develop cirrhosis, and another five to 10 years for liver cancer.

When people go to hospitals for pains in the stomach and abdomen, it is usually too late, Xiu says.

According to a recent national survey among HB patients conducted by Wu Jieping Medical Foundation, an organization affiliated with the commission, of the 2,043 hospital respondents in 20 provinces, and 848 online, about 53 percent of HB patients don't know anti-virus drugs can stop the virus from replicating, thus minimizing liver damage, and 20 percent of them haven't taken any anti-virus drugs.

With timely anti-virus and liver protection treatment, most HB chronic cases will not develop cirrhosis and liver cancer, and some even can reverse the liver damage, says Duan Zhongping, a liver-disease specialist and vice-president with Beijing You'an Hospital.

But many don't seek help, either because they don't feel the urgency or they cannot afford the drugs. The treatment of HB requires long-term medication intake, and prices of those medications vary. Most medications are not covered by public medical insurance, especially the expensive drugs.

Low-income patients, especially in rural areas, often choose low-cost and less-efficient treatment, and some do not take medication at all, according to Zhuang Hui, a hematologist with Peking University Medical Science Center and an academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering.

Fear of stigma

Sometimes, HB patients are so afraid of the social stigma that they choose not to see doctors regularly, and often miss the most opportune time for treatment, Duan says.

A Beijing disease-prevention specialist with a top medical university in China surnamed Cai, 48, knows the importance of prompt intervention to save the liver from HB virus.

Her 74-year-old father was diagnosed with liver cancer last week. Even so, Cai feels lucky that the cancer was detected early, and the situation is quite positive.

She credits this to the family's awareness of the damage HB can do.

Since her father was found with HB infection in 1985, the family has paid great attention to health checkups and liver protection.

Her father has a checkup, an ultrasound scan and other tests every year, and he then takes medications based on the checkup results.

When it is necessary, he will take liver protection and anti-virus medications. But when the liver seems in good status, he consumes no medication for fear of burdening the liver.

Physical tiredness and psychological stress will accelerate the liver damage caused by HB, but Cai says her father is careful to avoid those conditions.

Cai's grandmother probably died from HB, and five brothers and one sister of his father also died from liver disease, but the old man is at peace with his condition, and is very optimistic, Cai adds.

In 2010, doctors found milder liver cirrhosis in Cai's father, which was impressive since he has been infected with HB for about three decades.

Last week, during a regular checkup, doctors found a small malignant tumor on the edge of his liver.

"The size and position of the tumor is very suitable for surgical removal, and it was found early," Cai says.

"That's quite a comfort."

While HB is not that devastating as long as patients take good measures promptly, Cai says ultimately the solution lies in prevention rather than treatment.

Regretting that he missed the best window for treatment, Liu Junjie, the young man who died of liver cancer, devoted his last days to charity events for HB prevention and treatment, while going through torturous chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

"I am in a terrible tragedy, and I hope others will avoid such tragedy," Liu wrote in his twitter-like Sina Weibo.

Contact the writer at liuzhihua@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 07/24/2013 page9)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US diplomat says China ties a priority

Nation falling short on IT security

Weiner not dropping out of NYC mayoral race

Death toll from H1N1 in Argentina reaches 38

DPRK halt on rocket facility confirmed

Celebrations erupt after word of regal delivery

Office to close due to protest in Manila

Multinationals' dependence on China grows

US Weekly

|

|