Branding on brink of change

Updated: 2013-07-24 07:20

By Mike Bastin (China Daily)

|

||||||||

David Aaker, considered by many to be the 'grandfather' of brand building and branding as a separate and strategic management discipline, very recently produced a detailed discussion on the state of Chinese brands for the Harvard Business Review.

While few would dare to dispute Aaker's preeminence in the field of brand management nor his immense contribution to the literature, it is his apparent lack of knowledge of China and in particular the changing nature of Chinese business and consumer culture that renders his analysis questionable.

Essentially, Aaker contends that Western, especially US (surprise, surprise!) companies' record of successful brand building is born out of the rich pool of talented personnel available and a motivational force to 'go global'. Specifically, Aaker maintains that:

"Approaches to brand management [inside Western/US companies] have been created, tested, and refined by decades of smart people from varied perspectives and contexts."

The clear implication is Chinese companies still do not possess such smart people from a variety of backgrounds. Used to be true but less and less so. Younger generations of current and aspiring Chinese business and management professionals, especially those who grew up in a very different post-Open Door and post-one-child policy, possess an outlook and a skill set far removed from the traditional, Confucian set of values so deeply ingrained in the mindset of their forefathers.

A long-time resident of mainland China and researcher and consultant to numerous Chinese organizations, my findings that have surprised again and again are exactly these modern skills and open-mindedness of younger Chinese generations.

Growing influence

The issue, therefore, is the time it may take for the influence within Chinese companies, and Chinese society in general, for this increasingly independent, even unconventional, and crucially better-educated group of youngsters to reach critical level.

Aaker goes on to claim that "it is likely that brand building will hold back China's global prospects for some additional decades to come" but proffers no cogent argument behind this apparent capricious comment. For a more reliable source and someone whose research is grounded, indelibly deep inside the heart of Chinese society, Tsinghua's distinguished Professor Hu Angang provides us with a far more credible analysis of the pace of change across mainland China. Hu supports this bold assertion with the quantity theory of money as a suitable analogy. For example, it is often far easier and quicker for individuals and organizations to make the second million once the first was reached.

In the same way, Chinese industry's acceptance, adoption and successful implementation of a brand-building culture will follow an exponential path soon after China's army of modern and motivated youngsters close in on the stewardship of more Chinese enterprises.

Finally, Aaker does discuss some sort of way forward and out of this current brand management malaise. He turns to the acquisition of established foreign brands by Chinese companies as a way of "buying in' the required knowledge and experience". Aaker fails to establish the fact that any way forward for branding and brand management in today's constantly unpredictable and evolving global economy, has to be predicated on the equally changing and volatile nature of consumer brand behavior. Blind acquisition, therefore, of foreign brands and any consequent, yet equally myopic, management know-how transfer is highly unlikely to propel Chinese brands to global success.

Aaker's argument appears to follow the "logic" underpinning the spelling of American English, the unsurprisingly much-maligned derivative of THE English language, where the simplicity and short-sightedness of phoneticism replaces subtlety, invention and refinement.

It is also subtlety, invention and refinement that characterizes the inexorable and inevitable rise of this post-80s Chinese generation (the ba-ling-hou). This, and this alone, will bring about much-needed corporate culture modernization inside Chinese companies; which in turn will spawn the emergence of global Chinese brands, sooner rather than later.

The author is a researcher at Nottingham University's School of Contemporary Chinese Studies and Visiting Professor at China's University of International Business and Economics.

(China Daily USA 07/24/2013 page15)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US diplomat says China ties a priority

Nation falling short on IT security

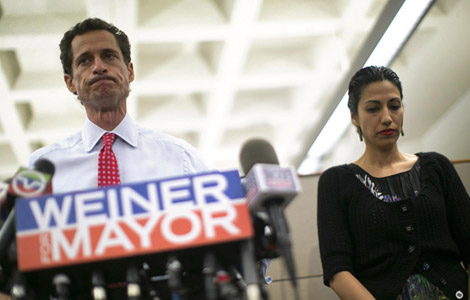

Weiner not dropping out of NYC mayoral race

Death toll from H1N1 in Argentina reaches 38

DPRK halt on rocket facility confirmed

Celebrations erupt after word of regal delivery

Office to close due to protest in Manila

Multinationals' dependence on China grows

US Weekly

|

|