Shine a light

Updated: 2013-08-14 07:40

By Erik Nilsson and Zheng Jinran (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

A young villager finishes palace lanterns at Tuntou village in Hebei province. The village is one of the wealthiest in the region because of the lantern-making industry. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

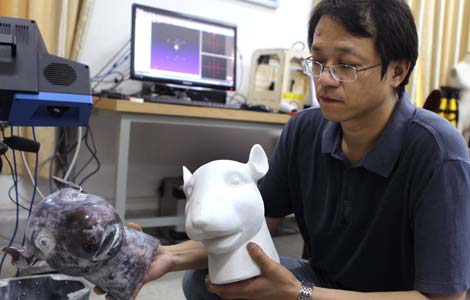

Zhang Fengjun, intangible cultural heritage inheritor of palace lantern-making, shows off a lantern made in his factory. |

|

Customers come to Tuntou village to buy lanterns as Lunar New Year decorations. |

Tuntou village has enjoyed a robust economy thanks to a thriving industry producing palace lanterns, but the intellectual property rights belong to only one person. Can the sole custodian of the intangible cultural heritage ensure the traditions are kept alive? Erik Nilsson and Zheng Jinran in Shijiazhuang report.

Tuntou village's palace lantern industry has produced a shining local economy that casts light on the role of intellectual property in passing on tradition.

Zhang Fengjun, 54, is Hebei province's only provincially designated intangible cultural heritage inheritor of palace lantern-making. Zhang owns nine patents related to the lanterns that were developed in the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25-220).

The fact that Zhang is the sole custodian of the lanterns raises the question: Does IPR illuminate or dim intangible cultural heritage's prospects?

Palace lanterns fueled the local economy during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), when an official discovered a local craftsman's lantern he suspected would delight the emperor.

It did. And an industry was born.

The local lantern-making tradition nearly flickered out in the following centuries but has enjoyed a revival in recent decades, making the settlement southern Gaocheng county's wealthiest.

"I've been successful in introducing this heritage to the market and industrializing it," Zhang says.

Zhang has also helped the commercialization of the industry. Many of the 300 types of lanterns his company produces are festooned with the logos of such behemoths as Bank of China, Tsingtao Brewery and China Mobile. Others are adorned with more traditional imagery - fish, representing longevity, and dragons and phoenixes symbolizing marital bliss.

He learned the craft from his father and founded Gaocheng Palace Lanterns Design and Development Co, Ltd, in 1984. It has grown to become the world's largest palace lantern producer with assets exceeding 19 million yuan ($3 million).

Lanterns have made remote Tuntou wealthy enough to get traffic jams, says village Party secretary Su Zhenguo, who also owns a lantern factory.

About 80 percent of residents have cars, and roughly 30 percent drive two. Typically, one is a family vehicle and another is a company van.

The average income among the nearly 6,000 villagers is about 15,000 yuan a year - far more than what an average Chinese farmer earns.

Youth can earn up to 150 yuan a day. Retired women can get about 70 yuan.

Currently, 110 employees make lanterns in his 16,000-square-meter factory.

An average employee's wage is about two-thirds of the bosses', Su says.

That includes thousands of migrant workers from nearby villages. "Villagers don't have to migrate from here," Su says.

"Instead, villagers migrate to here."

More than 10,000 people from some 1,000 families work in the sector. They produce more than 90 percent of the world's palace lanterns.

The research and development that forms the basis of Zhang's intellectual property rights are local. There are no outside designers, Su says.

Village-wide, the industry sells a billion yuan worth of lanterns a year, Su says. Twelve-meter-high lanterns sell for up to 80,000 yuan, while 3-cm-high models cost 8 yuan a pair.

Villager Li Yuping, who owns a small lantern-making company, says: "Chinese people want to decorate more as they become wealthier."

The local government offers preferential treatment, such as bank loans, to those who enter the sector.

Some might argue the IPRs contributed to Tuntou's prosperity - but Zhang is not among them. "Only one small factory has paid for the rights," he says.

"So, it can't be said my IPRs have made the village richer."

But he believes patents preserve heritage.

"Otherwise, the quality of the lanterns would vary. And competition could become malicious. That would hurt heritage. IPRs have made my company rich enough to develop new innovations on tradition."

He says the fee to use his patented designs is low but refuses to disclose the amount.

Patenting intangible heritage walks a fine line, China Art Institute researcher and doctoral supervisor Yuan Li says.

"Intangible cultural heritage is regional, which means it belongs to many people in a specific area," he says.

"Patents are exclusive. That runs against tradition and intangible cultural heritage's essence."

Other countries have been tackling this question for more than two decades with no clear solution, he points out.

The Indian government has gone to the mat over yoga patents awarded to US companies. It says "yoga theft" runs counter to the soul of the spiritual practice that's a part of shared traditional knowledge. India's government won the nullification of the multinational Metaproteomics' patent on ancient turmeric-based medicines Indian families use as folk remedies.

Two months ago, Good Morning to You Productions Corp sued Time Warner Inc's Warner/Chappell Music to demand a refund of the $1,500 licensing fee it paid the copyright holder of Happy Birthday to You - listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most recognized English-language song - arguing the traditional tune should be in the public domain.

Yuan says it's a blurry line between traditional craftsmanship and heritage forms' extrinsic features inherited by many people - which should never be patented - and innovative designs based on tradition. But patent offices lack mechanisms to measure the distinctions, he says.

An image database and recognition system would be an effective solution. India created one with 1,500 yoga poses to send to patent offices.

China Folk Culture Association deputy director Liu Delong believes patents could protect some crafts.

"However, some patents are too general," he says.

There have been lawsuits surrounding the name "Shandong brocade", for instance. The heritage form has no specific style, pattern or material.

Palace lanterns' IPRs haven't generated legal disputes.

Whatever their impact, business is booming. And the tradition is being continued.

Tuntou's industry is also bringing the Chinese intangible heritage form into international consciousness.

Zhang's company produced the lanterns that shone upon the Beijing Olympics and Shanghai World Expo.

They're exported to Australia, Russia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

And they dangle in Beijing's Zhongnanhai and the Great Hall of the People.

The village also produces customized moving lanterns - some are simple robots - of various shapes. Dragons twist, fish swim and birds fly in Gaocheng Palace Lanterns' display room. Fifty-six pairs of lanterns are shaped like couples from the country's ethnic groups.

Laser printers etch lanterns in the rooms surrounding a courtyard of vegetables in one section of the compound.

Su, the village head who runs another company, says Tuntou's palace lantern industry has illuminated opportunities for locals and offers a bright future.

"I used to make car parts," he says.

"Business was bad. So I started this. And business is brilliant."

Contact the writers through erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn.

Zhang Zixuan contributed to the story.

(China Daily USA 08/14/2013 page10)

Huawei unveil Ascend P6 smartphone in Vienna

Huawei unveil Ascend P6 smartphone in Vienna

That's one cool game of mahjong

That's one cool game of mahjong

Isinbaeva leads harvest day for host Russia

Isinbaeva leads harvest day for host Russia

Perseid meteor shower puts on show in night sky

Perseid meteor shower puts on show in night sky

Bird flu, slowdown hit sales at fast-food chains

Bird flu, slowdown hit sales at fast-food chains

PetroChina poised to dominate Iraqi oil

PetroChina poised to dominate Iraqi oil

Marriage attitudes slowly change

Marriage attitudes slowly change

On frontline of fight against crime

On frontline of fight against crime

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Brazil demands clarifications on NSA surveillance

2nd-generation ID cards to include fingerprints

Chinese students boost boarding business in US

TCM chain probed after illegal house exposed

Friends of accused Boston bomber due in court

Economic hub on Bohai Bay

PM to visit China for milk scare

Donors of organs easing transplant shortages

US Weekly

|

|