On the Road premiers in New York

Updated: 2013-10-09 10:34

By Liu Lian (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Inspired by a barroom quote from a Beat Generation classic - and about 1,000 other things - a new kind of dance work takes the stage in New York, Liu Lian reports.

What happens when Lijiang meets Jack Kerouac? On the Road, a mesmerizing 70-minute dance work by choreographer Cheng Tsung-lung, was inspired by a trip he took in 2010 with two dancer friends to Lijiang, an ancient town in Yunnan province.

The work's US premier was performed by three male dancers from Taiwan's Cloud Gate 2 Dance Theater on Wednesday at the Joyce Theater in New York.

At a bar in Lijiang, Cheng came across a quote in Chinese on the wall said to be from Jack Kerouac's Beat Generation classic On the Road, "everyone is a passenger in life's journey. No matter where you are, how you plod the path and what ideal you are after, you walk endlessly across landscapes until death catches up. Be realistic and stay true to your ideals while on the road." Cheng's trip to Lijiang, a remote spot in rural China, did fit in Kerouac's story that one has to travel afar in order to find oneself.

"Lijiang made me more aware of the existence of my two friends," said Cheng, referring to Chiang Pao-su and Luo Shi-wei, two of the three dancers on Wednesday night. "The two of them represent the two sides of me. Pao-su is close to me in reality, grass roots and adaptable, whereas Shi-wei represents the seemingly unattainable self, the wannabe - poised and gentle ... I sort of distanced myself from the two while we were on the road and was fascinated by my observations of how they interacted with the outside world, as well as with each other," he said.

The work took 6 months to piece together in 2010. Initially it was conceived with only the two dancers Chiang and Luo in mind, said Cheng, "and then it clicked to me one day that I was missing from the scene. Where am I? The seeing and the seen are constantly reversing. I am not only a spectator but a participant of the journey of self-discovery."

Chang Chien-hao, the third dancer, was invited to fill in the missing "self" halfway through the development of the work. "I was ill at ease when I first joined the dance as half of the moves had been set by then," said Chang. "The trip felt distant as I was never part of it."

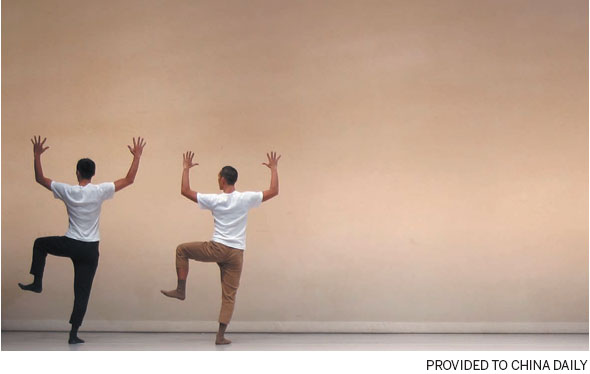

With a white wall as a backdrop, the staging felt strikingly neat yet barren in the glare of the white lighting. The trio, wearing no shoes and dressed in the same white T-shirts stained with black ink, were distinguishable only by the colors of their pants and socks.

One stood facing the wall in stillness, while the other two moved slowly in unison, one on top of the other, arms or sometimes legs crossed, reminiscent of a thousand-hand Bodhisattva. The pace of their steps soon gained speed, the interaction became more varied, suggesting internal struggles of the self.

The style was almost kaleidoscopic, a mix of Western and Eastern dance idioms. One could spot ballet, modern dance, hip-hop, and Peking opera styles, among others. The music also encompassed a variety of styles, including Taiwanese aboriginal music, Naxi ethnic songs, Islamic music, Tom Waits and the Japanese satsuma-biwa.

The moves were flowing and fluid, with brief pauses in between as the trio held their poses before transitioning to the next as if in slow motion, tantalizing the audience.

"As a choreographer, I tend not to define every single movement; rather, I dig tunnels and allow dancers to flow with their own interpretations," said Cheng. He worked with each dancer individually during the creative process, and in the end all the three dancers left their own impressions.

"People often ask how we can remember the more than 2,000 moves," said Chang, "it's not the brain at work but the body. Gradually the moves found their habitats insides our bodies and they flowed naturally when called forth. That's when I finally felt at home."

Midway through the performance, the music stopped. Luo placed a radio on the front of the stage, clicked it on and music resumed. The dancers withdrew to the sides of the stage and took out towels to wipe off sweat. The audience was not sure what was going on. Was the break intentional? Some burst into laughter. The distance between on- and off- stage seemed to suddenly dissolve. Wasn't the audience also acting its part in the eyes of the dancers? After all, aren't we all on the road?

Contact the writer at lianliu@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 10/09/2013 page10)

Last photos of Hungarian wingsuit diver

Last photos of Hungarian wingsuit diver

In photos: Typhoon Fitow aftermath

In photos: Typhoon Fitow aftermath

Japan-US military drill raises tension

Japan-US military drill raises tension

Higgs and Englert win physics Nobel prize

Higgs and Englert win physics Nobel prize In Bali, they relax in local fashions

In Bali, they relax in local fashions

Post office for Liaoning carrier opens

Post office for Liaoning carrier opens

A smog-filled Beijing targets polluting cars

A smog-filled Beijing targets polluting cars

Animal welfare to be added in training

Animal welfare to be added in training

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Trending News across China on Oct 9

Xiaomi's Barra ready to take on Beijing

A day of cultural exchange at Pace University

ZTE, Houston Rockets shooting for global markets

Global firms facing HR challenges in Asia

Back to 1942, entered for the 86th Oscars

Obama says he'll negotiate once 'threats' end

Unprotected sex brings sharp rise in HIV/AIDS

US Weekly

|

|