The dirt on tomb raiders

Updated: 2013-10-18 08:11

By Zhao Xu (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

Archeologists in race to save historic resources from plunder, Zhao Xu reports in Beijing.

For Qu Linxia, an archeologist who specializes in the excavation of ancient tombs, the time between the discovery of a centuries-old burial site and completion of its excavation is an emotional roller coaster.

"Sometimes my heart begins to sink even before we start digging," she said, referring to the sight of disturbed earth and discarded cigarette butts that almost unquestionably point to visits by tomb raiders.

But what Qu described as her "almost foolish optimism" keeps her hopes alive as she and her colleagues at the Shaanxi Provincial Archeological Institute carefully approach the core of each tomb.

"Usually, what we discovered was what we most feared: the lid of the coffin would be pushed aside, shards of pottery were scattered all around, embossed bricks that had prevented seepage for eons were broken or missing" said the 53-year-old, who as a youngster often accompanied her archeologist father to tomb sites, before taking on his mantle at the age of 16.

"On one occasion, we were greeted by nothing but a half-drunk bottle of mineral water."

The sight of the bottle, left behind as the raiders beat a hasty retreat, effectively ended a physically and mentally consuming process for Qu by extinguishing the faint glimmer of hope she had kept alive until then.

Army of grave robbers

The past two decades have seen more than 200,000 ancient graves plundered, many of which housed the remains of successive generations of emperors, kings and feudal lords. Nationwide, the army of tomb raiders is estimated at 100,000.

Arriving at a site hot on the heels of the archeological team, the raiders enter themselves in a race against their "official counterparts", one with which Wang Genfu, former director of the archeological team of the Nanjing Museum, is all too familiar.

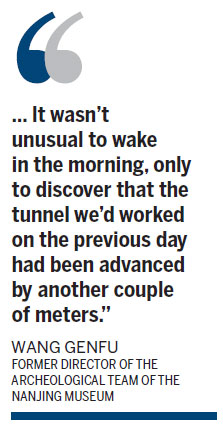

"There were extreme cases when we dug from one side of a site while tomb raiders dug from the other. It wasn't unusual to wake in the morning only to discover that the tunnel we'd worked on the previous day had been advanced by another couple of meters," said Wang.

"We considered ourselves extremely lucky if our 'nighttime helpers' had failed to reach the tomb chambers."

It would be wrong to think of tomb raiders as a band of ill-educated, money-minded outlaws who use primitive methods to try and make the most of an archeological discovery.

Equipped with metal-detectors, oxygen-generators and a reasonable amount of professional knowledge, modern-day tomb raiders are entirely capable of striking out on their own. Their efficiency and the level of destruction they wreak on the sites enrages and saddens the archeologists.

No easy answers

There are no easy answers to the problem, according to Wang, who said if anyone is to be held responsible, it would have to be various levels of government, especially those at provincial, county and village levels.

The indifference of those in direct charge of tomb security, and their sometimes thinly veiled cooperation with criminals, disturbs the 52-year-old.

Wang, who has lowered himself into several thousand ancient tombs during his three-decade career, recalled a teacher-cum-tomb protector he knew in his native Jiangsu province in the 1980s. "He was the only holder of this official position in his county; he familiarized himself with every known tomb site in the area and kept a close eye on them the way a mother would her toddler," said Wang.

"Although he retired nearly two decades ago, the county museum is still home to the many earthenware utensils and gold accessories he managed to save just moments before their planned disappearance, sometimes risking his own life in the process."

Even though the cultural relics bureaus are employing more "tomb protectors", Wang complained that the positions are often handed out as sinecures as a result of nepotism.

However, the archeologists and historians admitted - with some reluctance - that a dark secret exists within the archeological world.

"You may not believe it, but on, admittedly infrequent, occasions, archeological teams have actually let the tomb raiders do their work while they waited in the wings," said Ni Fangliu, a writer-historian whose 2008 book The History of Chinese Tomb Raiding is considered a seminal work, both for its rigorous scholarship and its highly engaging style of writing.

The cardinal rule

The policy that still serves as the cardinal rule for Chinese archeologists was first shaped more than half a century ago and may be partly to blame for the present situation, according to Ni, who said, "The roots of this very strange scenario lie in the past as much as the present."

In 1956, the biggest archeological project of the era, the excavation of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) Dingling Mausoleum, eventually got underway after long debate.

During the following two years, countless treasures were unearthed at the site, but an invaluable discovery became a permanent loss.

The archeological teams lacked adequate conservation skills and gorgeously brocaded silk fabrics, preserved in pristine condition by the lack of oxygen in the tomb, quickly lost their luster and some simply disintegrated.

At that point, Zhou Enlai, China's premier at the time, stepped in. He made it clear that there would be no more "active archeological excavation" on Chinese soil, only "rescue missions".

In practice, it meant that the archeologists would not be allowed to excavate ancient burial sites unless their survival was in danger, either by large construction projects or by being plundered by unwelcome visitors.

The only sites exempt from the ruling were those whose excavation was deemed absolutely essential for studies in the related areas.

Over the past decade, as free-diving tomb raiders punched a couple of million holes in the ground in search of graves, the policy has been widely questioned.

The main criticism is that it deprives archeologists of the chance to make their own "pre-emptive strikes".

No project, no funding

Not only does the policy deny archeologists the chance of uncovering priceless objects and knowledge, but also has profound implications for funding.

"With each excavation project at hand, archeological teams apply for government funding, which they then rely on to pay for their daily operations," said Ni.

"No project equals no funding, and lower incomes for the members of the teams, which explains why they will allow tomb raiders to go in first - to make the site accessible to themselves," he said.

However, despite its shortcomings, few experts believe the policy should be abandoned.

Yue Nan, a writer-historian who has written an account of the excavation of the Dingling Mausoleum, said: "We cannot afford to forget the lessons of the past. That principle should be upheld in the foreseeable future, and not only because we are still at a relative rudimentary stage as far as the conservation of delicate antiques is concerned.

"Forgive me, but archeological excavation shares at least one thing with tomb raiding: Both have removed millions of antiques from their original historical and anthropological contexts, thus rendering them trivial if not completely meaningless."

Wang shares Yue's view. "My sense of accomplishment comes from the integrity of the tombs. Whatever is dug up testifies to the greatness of our ancestors," he said, adding that while protection is paramount, archeological research is crucial to the preservation of memories that would otherwise be totally erased.

"Even a desecrated site speaks to me," he said.

Back in the 1950s, when some of China's leading academicians petitioned for permission to dig the Imperial Mausoleum of Emperor Qing Shi Huang, who unified China for the first time in 221 BC, Premier Zhou told them, "Let's leave something for those who come after us."

Keepers of the flame

Yang Xiaochen belongs to that group. For the past decade, the 29-year-old Beijinger, a member of the "Tombs Association", has regularly spent his weekends wandering around the suburbs of Beijing in search of ancient tombstones.

"A lot of the tombstones I first discovered as a teenager have now disappeared, presumably having been stolen to be sold at antiques markets," said Yang, who these days pays increasingly frequent visits to the sites.

"Sometimes, I return a month later to find the inscribed steles have gone, there's just a vague, wet mark left on the ground," he said.

"This may sound fatalistic, but to me graves are like grandparents; you cross your fingers and hope they'll live forever, all the while knowing that they'll be gone, maybe in the not-too-distant future. But at least I have the photos."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

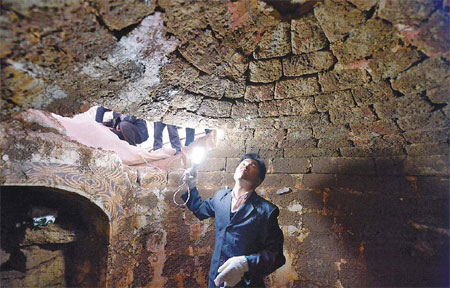

An archeologist studies murals in a tomb from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), which was found in Xingzi, Jiangxi province, during construction work. Zhou Mi / Xinhua |

|

This tomb dating from the Northern Song Dynasty (AD 960-1127) was discovered near a residential community in Xiangyang, Hubei province, earlier this year. An Fubin / Xinhua |

(China Daily USA 10/18/2013 page6)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US not budging on its arms restrictions on China

China's GDP rises 7.8% in Q3

China warns of emerging markets' slowing demand

Roche boosted by strong drug sales in US, China

IBM's China-driven slump sparks executive shakeup

Can cranberries catch on in China?

Asia-Pacific pays executives world's highest salaries

US debt deal a temporary fix

US Weekly

|

|