Ancestor hunter

Updated: 2014-10-14 07:29

By Liu Zhihua(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

A Dutch citizen eager to trace back his family history now helps many overseas Chinese do the same, Liu Zhihua reports.

Huihan Lie, a 36-year-old Dutch citizen, never expected he would someday make a profession out of helping fellow overseas Chinese find their roots through jiapu or "ancestry book", when he first visited China in 2004.

Jiapu, also called zupu in Chinese, are records that are kept by clans of their lineage and histories. Lie didn't know much about jiapu until he came to China.

|

Members of the Hus clan gather at a village in Jilin city, Jilin province, to renew their jiapu in 2012. Sun Xin / For China Daily |

|

Lu Hongman, a resident of Gushi county, Henan province, displays his family's jiapu with a history of 300 years. Xiang Mingchao / For China Daily |

|

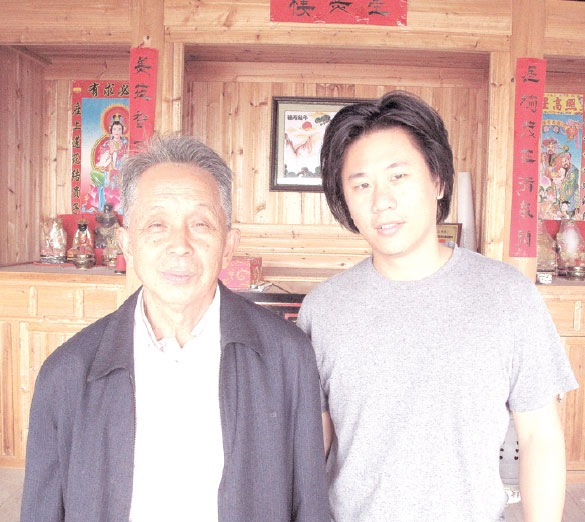

Huihan Lie (right) with a distant kin in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. Provided to China Daily |

He was born in Amsterdam, Netherlands, to a family that emigrated from Indonesia, with Chinese origins on both his parental sides. But no one in the family spoke Chinese.

In 2003, Lie decided to learn the language after he obtained a master's degree in international law at University of Amsterdam.

"We look Chinese but we speak Dutch, and that made me wonder about my family history," Lie says, adding that he had peppered his father and grandfather with questions about his family history since he was a teenager and was always interested in China.

After studying Mandarin at Beijing Language and Culture University for two months, Lie decided to stay longer and says he worked at international enterprises.

A few years later, he decided to pursue his interest in history and genealogy, to help others find their roots.

"Many overseas Chinese don't speak Chinese and cannot make good use of jiapu or other important files," Lie says.

In 2012, he founded My China Roots, which specializes in jiapu and Chinese ancestry.

With two colleagues, he starts each job by asking clients, mostly through Skype and e-mail, to gather what they already know and have - old pictures, passports and other documents.

Armed with those resources, Lie's small team acts like detectives to figure out where a client's original village is located.

Overseas Chinese affairs offices or associations at the country or city level, which are government-supported organizations, often help Lie's team, because they are able to tell where a clan of Wangs or Xies has probably lived for hundreds of years.

Then the researchers will visit the village, talk to locals and examine jiapu to make sure it is actually the ancestral village.

"Nothing is more important than jiapu in the whole roots-seeking process," Lie declares.

Unlike in Europe and the United States, where governments and churches keep most records of births, marriages and deaths, in China, families have used jiapu as their own documentation of family history.

Such an ancestry book often stretches across centuries and sometimes can go back thousands of years.

It is also more than a family-tree record. The top 100 Chinese family names account for most of the Chinese population, and jiapu are critical in tracking the growth of a clan's members with the records of their political, military and academic achievements.

There are often biographies of prominent people, and jiapu also records important events that have happened to the clan, such as where and when the clan moved from one place to another, and why.

But because of the language gap and loss of information during translation, or because of the difference between a formal name that has been written down in jiapu and a nickname that is used in daily life, it is sometimes very hard to identify a client's roots, Lie says.

Besides, many jiapu have been destroyed or lost during China's transformation from an agrarian to an industrial society, and during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

Lie always copies jiapu whenever possible, hoping to help preserve the jiapu legacy.

In 2008, Lie started digging into where his own ancestors were from, and soon traced his mother's roots to a village near Zhangzhou, Fujian province, which the family left seven generations ago.

That was also the first time he saw a jiapu.

But tracing his father's family history required much more effort.

Finally, after finding the name of the original ancestral village written on his great-grandfather's tombstone in Indonesia, he narrowed down his paternal ancestors' origins to a village called Zhu Shan on Jinmen island, which was once part of Fujian but is now administered by Taiwan, and found out his father's ancestors left six generations ago for Indonesia.

His investigation gained him a reputation among his friends, many of whom are overseas Chinese eager to know more about their Chinese roots.

"Seeking roots for an overseas Chinese is a combination of exploring history, culture and psychology. I make less money but I am happier," he says of his decision to quit a well-paid job with an international firm and launch his own company on genealogy research.

Earlier, Chinese people left their homeland mostly because of poverty, war or social unrest, and clients are often inspired by the personal stories of their forefathers written in jiapu and then feel a stronger bond with China, Lie says.

So far his company has unearthed the Chinese roots of more than 25 clients from the US, Europe, Australia, Central America and elsewhere.

"I'm moved by what you do. Great job and wish you all the best!" says one post on the company's Sina Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter.

Contact the writer at liuzhihua@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily USA 10/14/2014 page8)

New York celebrates 70th Annual Columbus Day

New York celebrates 70th Annual Columbus Day

Child bride 'marries' 37-year-old

Child bride 'marries' 37-year-old

China, Russia sign deals on energy, high-speed railways

China, Russia sign deals on energy, high-speed railways

Chinese art troupe displays power to overcome obstacles

Chinese art troupe displays power to overcome obstacles

30 most beautiful counties in China

30 most beautiful counties in China

Largest drum-shaped building in Hefei sets Guiness record

Largest drum-shaped building in Hefei sets Guiness record

Nixon Remembered

Nixon Remembered

Premier Li lays wreath at Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Premier Li lays wreath at Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Alibaba set to expand 'double 11'

DPRK's Kim makes first public appearance in 40 days

HK police vow minimum force to remove protest road barriers

Ferguson protesters struggle to keep focus on slain teenager

Canadian Ebola vaccine begins human testing

Coal taxes could impact market

Shanghai troupe to honor Chinese educator in NYC

High-speed rail deal part of $10b agreements

US Weekly

|

|