Getting to know Chinese Americans who went home

Updated: 2015-11-20 12:26

By Niu Yue in New York(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

In the early part of the 20th century, roughly one out of five Chinese Americans returned to China, most on the assumption that they would never permanently come back to the US, according to new research by a China studies expert.

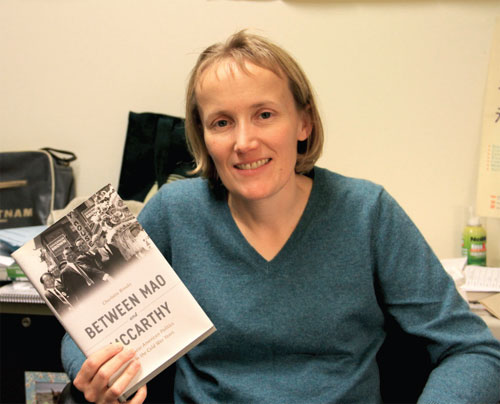

Charlotte Brooks, a history professor of Asian and Asian American studies at Baruch College, said overseas Chinese returnees were seeking opportunities in their motherland when the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act was in effect.

According to Brooks, there were two major categories of returnees: children sent by their parents to the motherland and adults seeking better career opportunities in China.

Children were usually sent to a village or church school for security reasons. "Some of them were kidnapped by malicious gangsters, because most of the kids were financially well-off and ransoms were usually priced high," Brooks said.

Piles of diplomatic archives indicate some of the kids suffered from the dual-nationality dilemma, said Brooks, but fortunately most of them were set free eventually.

Adults who went to work in China experienced more ups and downs in the war-torn country, her research shows.

Until the abolishment of Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, most Chinese citizens could not immigrate to the United States except as students, diplomats or other "high-ranking" status.

For those who were naturalized as American citizens before the law, where situation was worse. A broad range of US public sectors prohibited Chinese Americans from employment and the Great Depression added salt to wounds of unemployed Chinese Americans.

From 1910 to 1940, according to San Francisco's immigration authorities, 56,113 Chinese people immigrated to the US and more than 30 percent of them returned to China.

Adult returnees went for "business and patriotism", said Brooks, and "many of them climbed to the upper class in China."

Brooks' research shows that for most of the returnees, life improved in China.

Arthur Chin, a former US Navy officer, went to China and joined the Chinese navy in the Chinese People's War Against Japanese Aggression and was eventually promoted to battalion chief in 1939. He returned to the US and worked as a post office clerk until retirement.

In 2009, then President George Bush signed a bill designating a facility of the US Postal Service as the Arthur Chin Post Office.

Retrieving cases from the counselor records in official archives is a challenge for doing research, Brooks said.

Brooks has visited the national archives in several Chinese cities, including Guangzhou, Nanjing and Taipei.

Some of the archives are so covered with dust that "it seems like new territory untouched since they were deposited in the 1920s or 1930s".

Last year, Brooks visited China and took photos of 3,000 pages of records, but they are still just the tip of the iceberg.

Brooks said the records were basically people's identity registration and records of their troubles.

"What surprised me most was the number of kidnappings and political problems," she said.

"Basically, it was about people," Brooks said, adding that she is building a database of returnees' names. "People will feel excited about their family history."

The nicest thing about doing the research, she said, is helping Chinese Americans understand more about their motherland.

Long Yifan contributed to this story.

|

Charlotte Brooks, professor of Asian and Asian American studies at Baruch University, found that about 15-to-20 percent of all Chinese-American citizens went back to China in the first half of the 20th century. Long Yifan / for China Daily |

(China Daily USA 11/20/2015 page2)

- London tube station evacuated over security threat

- China law firm Yingke opens China Center in London

- ROK accepts DPRK's proposal for working-level talks

- DPRK proposes working-level talks with S. Korea

- France, Russia launch more strikes against IS targets in Syria

- Chinese bearing maker prepares Michigan facility

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Automakers debut key models at LA Auto Show

Automakers debut key models at LA Auto Show

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

Xi pledges $2 billion to help developing countries

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US Weekly

|

|