Students cross the line to catch a class act

Updated: 2016-05-04 08:02

By Shadow Li inHong Kong and Chai Hua in Shenzhen(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Many children from the mainland commute to Hong Kong every day to attend school as their families look to use the advantages offered by the city's Western-style education system, report Shadow Li in Hong Kong and Chai Hua in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

Three years ago, when her 2-year-old son had a fever that sent his temperature soaring to 39 C, Zou Fang rushed more than 100 km to the hospital in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

The moment she entered the ward, though, her son, named Xuanxuan, said he didn't want to see her and asked her to leave.

Zou, who was living and working in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong, was devastated. She was overwhelmed with guilt at not being there for her son and realized she had to make a choice between her work and family commitments.

Then 32, Zou immediately quit her job as second-in-command at the South China office of an advertising agency and moved back to Shenzhen to repair the breach with Xuanxuan, who had lived with her mother since he was born.

Zou said it was the hardest decision of her life, but in retrospect, it was the wisest she ever made.

It took six months to restore her relationship with her son. She took him to the park every day and spoke with him at length to improve his language skills, which were extremely poor, and far worse than those of children of the same age in Shenzhen and neighboring Hong Kong, where her son was born and her husband has permanent residence.

The months she spent with Xuanxuan also gave Zou time to think about the things she valued most in life.

Zou and her husband met in Guangzhou and married after a seven-year relationship. Xuanxuan was born five years ago.

After making the momentous decision to give up her career and care for her son, Zou was faced with another dilemma-where should he be educated? Because Xuanxuan has permanent residency status in the city of his birth, he was eligible to be educated in Hong Kong, so Zou spent six months researching schools and preparing her son for school at a well-respected kindergarten.

Despite her months of preparation, there were still plenty of surprises in store for Zou. She and her husband had to line up all night just to get an application form for the Fung Kai Kindergarten, a top institution in Hong Kong's North District.

The couple was shocked by the other parents' enthusiasm and the preparations they had made for the vigil. Many arrived equipped with sleeping bags and other items to help them endure the long night, while Zou and her husband only brought one portable chair.

It was worth the effort, though; although there were more than 2,000 applicants, Xuanxuan was one of just 200 children admitted to the kindergarten that year.

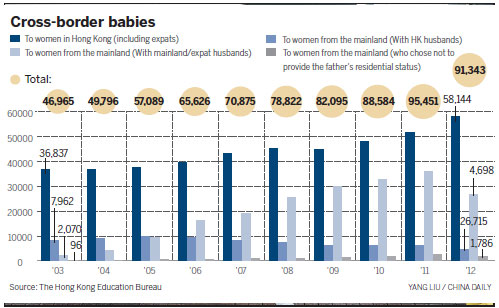

Student numbers soar

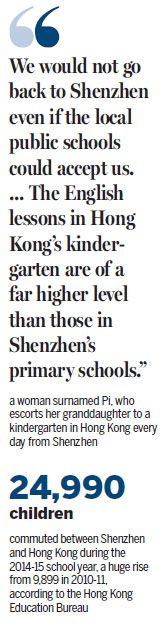

Zou's son was one of more than 24,990 children who commuted between Shenzhen and Hong Kong during the 2014-15 school year, a huge rise from 9,899 in 2010-11, according to the latest data from the Hong Kong Education Bureau.

In light of the rise in numbers, several proposals have been put forward, including suggestions that Shenzhen's public schools should be opened to cross-border students with permanent residence in Hong Kong. Most of them have mainland parents, who have no right to reside in Hong Kong, but the others are the children of people from Hong Kong who live and work on the mainland.

Back in 2013, lawmaker Ip Kwok-him, a Hong Kong deputy to the National People's Congress, took the issue further by proposing that not only should those students be accepted at Shenzhen's public schools, but that Hong Kong-style schools should be built in the city to offer the Hong Kong curriculum and better cater to their needs.

However, the proposals seem far from realistic because the Hong Kong education system can't be imported to the mainland exactly as it is, which would compromise the wishes of parents to choose it rather than schools across the border, according to Jeff Leung Pingkin, a spokesperson for the Concern Group on Policies for Cross-border Students, an NGO in Hong Kong which monitors cross-border education.

In 2013, the Hong Kong government introduced a "zero delivery quota", to redress the balance after a 2001 ruling by the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal granted permanent residence to all infants born in the city. The ruling led to an influx of non-locals who wanted their children to be born in the city.

More than 202,300 non-local children had been born in Hong Kong by the time the ban was imposed. They have permanent residence, but their parents, who are mostly from the mainland, don't, so the children live in Shenzhen and cross the border every day to go to school.

The number of children crossing the border for schooling will peak in the 2018-19 school year, before gradually decreasing, according to the Hong Kong Education Bureau, inane-mailed reply to questions from China Daily.

The bureau said the government has no plans to build Hong Kong-style schools on the other side of the boundary, saying the surge in demand for cross-border school places is "transient". It also cited regulatory and operational difficulties, and the financial implications for publicly funded schools outside Hong Kong.

The bureau has encouraged Hong Kong-born children who live in Shenzhen to attend primary schools in the mainland city, as provided by the Classes for Hong Kong Students Program, which make provisions for children born in the city to be educated in Shenzhen.

In 2013, the program was extended to children whose parents are not permanent residents of Hong Kong, and this academic year has seen 3,100 Hong Kong-born students in Shenzhen being taught in privately operated establishments known as "Minban" schools.

Although she agreed that more options in Shenzhen would help the children, Zou won't let her son attend a public school in the city.

"I never thought about putting him in a school in Shenzhen - neither the public schools, nor the international ones," she said.

Leung said many parents made a conscious decision to give birth in Hong Kong because they want the next generation of their family to be educated in the city's more cosmopolitan, international environment.

Some of the parents regret having no option but to send their children to Hong Kong, according to Leung, who is assisting several cross-border students. The children are not allowed to study at public schools in Shenzhen, which have a limited number of places for children with hukou, or residency permits, so the only alternatives are private or international schools, which are far beyond the price range of most families.

Frustrations grow

That means crossing the border for education. However, the process is problematic, with a long commute, eating on the move, less sleep and, for many children, no after school activities. Moreover, some of the children find the cultural and language barriers frustrating.

"We would not go back to Shenzhen even if the local public schools could accept us," said the grandmother of a young girl as they approached the checkpoint between the two cities. The woman, who only gave her surname as Pi, said neither her daughter nor her son-in-law is a Hong Kong resident.

Pi had just one aim when she traveled from her hometown in Heilongjiang province in the far northwest to the very south of the country -

to escort her granddaughter to a kindergarten in Hong Kong every day.

The roundtrip takes more than four hours, but "it doesn't matter", according to Pi, who said the schools inHong Kong will give her granddaughter "a better education and, therefore, a better future".

"The English lessons in Hong Kong's kindergarten are of a far higher level than those in Shenzhen's primary schools," she said, adding that linguistic skills will be an important advantage in the search forwork later in life.

Speaking with a strong northeastern accent, Pi said she doesn't understand Cantonese, the dominant language in Hong Kong, but her granddaughter speaks it "very well". Unlike many of her mainland peers, the 4-year-old attends several after school activities."So she can establish close relationships with local children," Pi said.

Zhou Jianfeng, the founder of Siyuan, an educational NGO in Shenzhen that helps cross-border students, said quality of education, rather than cost, is the main reason parents' choose to send their children to Hong Kong schools.

He said grade three, primary school students in Hong Kong have a vocabulary equal to that of students in Shenzhen's middle high schools.

Another factor is that children educated in Hong Kong have a far higher chance of being admitted to the city's universities than children at the same level who were educated on the mainland, he said.

Fundamental factors

As long as these fundamental factors remain, parents will not change their preferences, Zhou said, adding that some parents are even willing to let their children attend schools near the Hong Kong airport, about 50 minutes from the border.

Echoing Zhou, Leung said the fact that Hong Kong's education system is recognized and respected overseas, especially in countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia, is one of the biggest incentives for the long years of commuting across the border.

He said most cross-border students will eventually reside in Hong Kong, because they were born there. However, without a sustainable system to support them and provide a proper education, they may not be suited to joining the labor force, which was the primary aim of the city government when it granted permanent residence to children born to non-residents, and could even put great strain on the social welfare safety net.

As the number of cross-border students is likely to stabilize in three years time, support for them will inevitably weaken as well, he said, noting that the problem will have to be resolved by the governments of both Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

In just a few years, questions about the children's education will cease to be pertinent, but other problems will remain, such as whether there will be enough housing to accommodate them when they are ready to move to Hong Kong and if there are enough measures to keep them in the city and contribute as they are expected to.

Zhou, from Siyuan, believes that both the mainland and Hong Kong should pay more attention to the conditions in which the children live and are educated because they can play an important role in promoting integration.

Zou, whose son will start primary school in about 18 months, has already prepared for another battle ahead. When Xuanxuan started at kindergarten, she and her husband started their own jewelry company to ensure they will have more time to devote to him.

"I am considering buying a flat in the North District and cutting my working day from 70 percent to just 30 percent to prepare for my son's life at primary school," she said.

Contact the writers at stushadow@chinadailyhk.com and grace@chinadailyhk.com

|

Children prepare to enter Hong Kong at Futian Port in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, on April 14. They were born in Hong Kong and go to schools there, but live in Shenzhen. Photos By Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Crossborder students from Shenzhen arrive in Hong Kong through Lok Ma Chau Port on April 14. |

(China Daily 05/04/2016 page6)

- 500 million people at risk of contracting Zika in Americas: PAHO official

- UN urges DPRK to stop 'further provocative action'

- China stresses Putin's expected visit

- British FM visits Cuba for 1st time since 1959

- Trump attacks Clinton on gender, risking backlash from women

- Pirate radio poses surprising challenge in internet age

Olympic flame lands in Brazil for 94-day relay to Games

Olympic flame lands in Brazil for 94-day relay to Games

Top 10 least affordable cities to rent in

Top 10 least affordable cities to rent in

Exhibition of Tibetan Thangka painting held in Lhasa

Exhibition of Tibetan Thangka painting held in Lhasa

Storm's aftermath is a pink petal paradise

Storm's aftermath is a pink petal paradise

Xinjiang-Tibet Highway: Top of the world

Xinjiang-Tibet Highway: Top of the world

Female patrol team seen at West Lake in Hangzhou

Female patrol team seen at West Lake in Hangzhou

Drones monitoring traffic during May Day holiday

Drones monitoring traffic during May Day holiday

Sino-Italian police patrols launched in Italy

Sino-Italian police patrols launched in Italy

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Liang avoids jail in shooting death

China's finance minister addresses ratings downgrade

Duke alumni visit Chinese Embassy

Marriott unlikely to top Anbang offer for Starwood: Observers

Chinese biopharma debuts on Nasdaq

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

US Weekly

|

|