Watching the water

Updated: 2013-11-06 07:00

By Wu Ni (China Daily)

|

||||||||

When Quzhou lawyer Dong Zheng noticed paddy fields turning barren from the illegal dumping of untreated waste water, he knew something had to be done. He has now become a dedicated environmental crusader. Wu Ni reports.

Carrying a camera and strolling along the riverbank, Dong Zheng could be any tourist. But Dong is not enjoying the scenery. He is looking for hidden threats to the landscape, drainage outlets through which factories discharge untreated wastewater.

Over the past four years, Dong, a lawyer in Quzhou in China's eastern Zhejiang province, has volunteered to search for concealed pollution outlets and regularly monitor wastewater with a group of local volunteers.

When the volunteers discover wastewater has been discharged without being treated, they report to environmental authorities, and sometimes expose the case to the media.

It was by chance that Dong, 53, became known for revealing illegal pollution drainage, earning him the title of "environmental protection pioneer" of the city.

In March 2009, when Dong drove past a village in the city's Qujiang district, he was surprised to find a large section of paddies overgrown with grass. Local farmers said a chemical factory nearby had discharged industrial wastewater into the field, making the fertile rice field nearly barren.

"I felt indignant and was determined to make clear the truth," Dong recalls.

He consulted a friend and learned the simplest way to detect the quality of wastewater was to use a pH test strip. The result was shocking: the pH level of the water in the field was 1, indicating strongly acidic water.

"It was obvious that the wastewater was discharged into the rice field without being properly treated. It not only spoiled the land, but also flowed into streams that finally led to the river," he says.

Villagers had complained to the local environmental protection bureau but did not receive any response, so Dong turned to the media for help. After the incident was exposed on the Zhejiang TV station, the chemical factory was ordered to shut down until it had qualified wastewater treatment equipment.

It was no secret that companies unwilling to invest in wastewater treatment equipment would stealthily drain wastewater and the government sometimes turned a blind eye because many of these factories are major taxpayers and employers, Dong says.

Quzhou has established seven industrial development zones and is the home to the biggest fluoride chemical base in China. Municipal government statistics showed the city's chemical industry contributed 23.98 billion yuan ($3.93 billion) in production value last year.

Dong admits that environmental protection bureaus would act much quicker when the media get involved but he tries to avoid the situation because "the exposure, more or less, would embarrass local authorities while a cooperative relationship would be conducive to the cause".

In many cases, factories accumulated untreated wastewater and piped it out deep in the night or on rainy days, Dong says: "The more heavily it rains, the more important it is we take action."

Some factories transported wastewater with trucks and poured on the mountain. To collect evidence, Dong even pretended to be a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine scouting for herbs on the mountain.

Once, volunteers secretly followed a truck and took photos to record how untreated wastewater was poured on a nearby mountain. They were discovered by the factory's security guards, who confiscated their camera. Luckily, Dong had taken out the memory card before the guards took the camera.

Dong was fully equipped to look for hidden outlets: He had a camera for collecting visual evidence, a flashlight for night patrols, insect repellent used in some pollution outlets and long rubber boots because he often had to wade through polluted water, and most importantly, the pH test strips.

He later was given more professional pollution-detection equipment by Hangzhou-based e-commerce giant Alibaba Group, who initiated the Qingyuan Action for water protection in 2011. The project aimed to build a platform for individual participation and to encourage local nongovernmental organizations to assist the provincial government in water protection.

Dong, along with more than 30 volunteers, including lawyers, students, taxi drivers and salesmen, were invited to be river monitors. Twice a week they visit the three main stretches of the Qujiang River, the main source of the Qiantang River that runs through southeast China, investigate pollution sources, take photos, perform basic water quality tests and report problems they find.

Xu Jianfang, a 40-year-old taxi driver in Quzhou, was persuaded by Dong to join the action in 2011. Now he is the backbone of the group.

"Actually Dong did not talk too much but said some simple truths: Water quality is vital to health and to our children. It was the right thing," Xu says, adding that he was also touched by Dong's passion for the cause.

Xu is responsible for monitoring the 40-km-long Wuxi River with about 40 to 50 industrial wastewater outlets. He says factories are now under more pressure thanks to the cooperation between NGO and governmental environment supervisors.

"We would first inform the factory if we found it discharged untreated wastewater. Many of them knew us, and would stop pollution immediately. They knew if they ignored it, we report to the authorities," he says.

About 82 percent of China's rivers and lakes are affected by different levels of pollution, according to Wang Hao, an expert from the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research.

In the highly industrialized southeastern Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta, it is common for 500 to 600 factories to be crowded along a 100-km-long riverbank, which means the discharged pollutants are far beyond the river's capacity to absorb them, Wang says.

He suggests raising the industrial water drainage standard and increasing the pollution discharge fees might help.

At the grassroots level, Dong, who has been fully devoted to the project, believes it is the attention and action from ordinary people that can change the situation. "As a lawyer I work for the benefit of my clients. Now I work for the good of the majority. This inspires me to carry on," he says.

Contact the writer at wuni@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

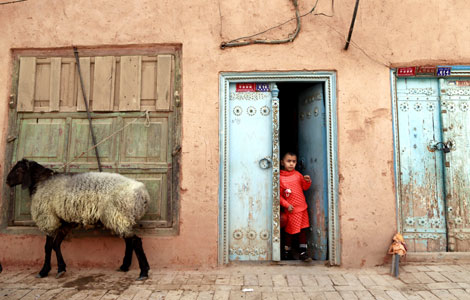

Dong Zheng discovers wastewater that has been discharged without being treated in Quzhou, Zhejiang province. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

Dong tests the quality of wastewater discharged from a factory with a pH test strip. |

(China Daily 11/06/2013 page20)

Post-baby Duchess

Post-baby Duchess

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China seeks cooperative efforts on nuclear safety

Shanghai still the favorite city for expats

Venezuela says US spies on it for resources, oil

More direct flights to tourist destinations

Brazilian govt to use anti-spying email system

US media under attack for 'double standards' on terror

Alipay partners with UATP

Minister proposes security fix

Minister proposes security fix

US Weekly

|

|