Running wild

Updated: 2014-01-16 07:32

By Deng Zhangyu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The rare milu deer are growing in number, but a battle for space may threaten the future of this fascinating animal. Deng Zhangyu reports.

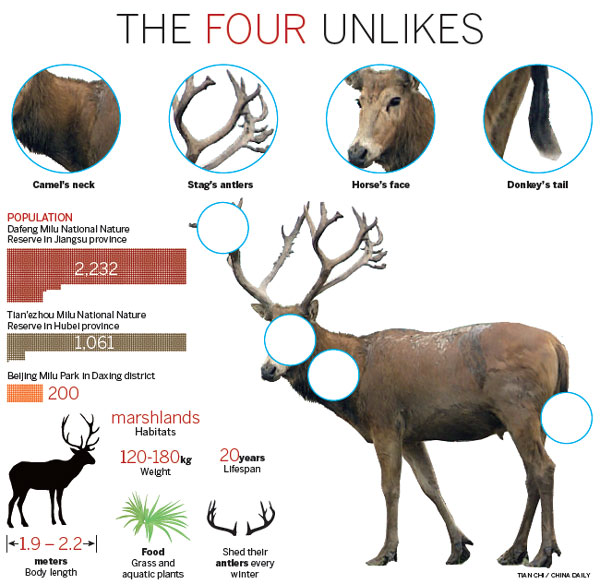

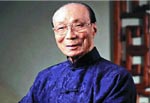

A herd of Pere David's deer lower their heads to drink water from a mud flat. Always vigilant, they occasionally look around to check for danger. Behind them is a vast land of reeds where they like to hide. Pheasants duck in and out of the reeds and wild geese take to the skies. This is the Tian'ezhou Milu National Nature Reserve in Shishou, Hubei province. Surrounding the reserve are miles of farmland dotted with cottages, but in the reserve, animals and nature run wild. There are 1,061 milu - the Chinese name for the deer unique to the country - in the reserve. It's the largest wild herd in China and in the world, all descendents of the 94 deer shipped from Beijing's Milu Park in the 1990s.

"Our mission is to help the milu return to the wild. After years of efforts, we've made big progress," says Li Pengfei, director of the research department at the reserve.

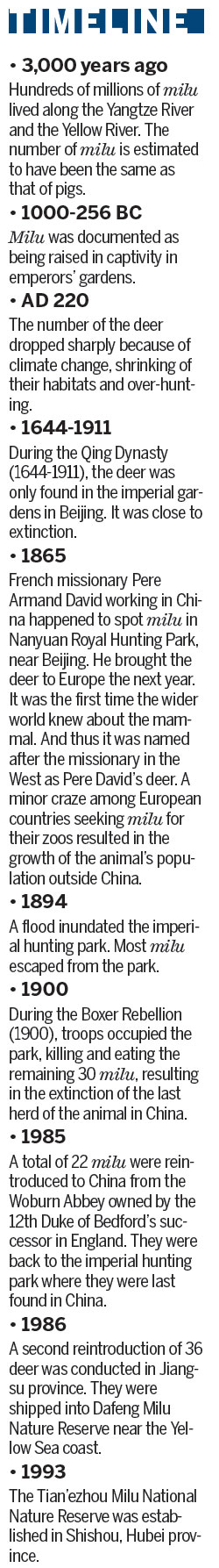

A century ago, milu, known as Pere David's deer in the West, were said to no longer live wild in China. There were only 18 of the animals living in China in 1898. The shortage was the result of European zoos' desire to collect exotic animals. In 1986, 22 milu were reintroduced to Beijing's Milu Park and another 39 were later shipped to Dafeng in Jiangsu province from Britain.

Milu in Beijing and Dafeng, says Li, are semi-wild, meaning they are fed by people. But staff in Tian'ezhou seldom feed the deer, except when the area is hit by snowstorms or drought. Tian'ezhou milu reserve is not open to the public. Only staff or experts conducting research are allowed to visit the wetlands, says Cai Jiaqi, director of the public education department of the reserve.

The 1,567-hectare reserve was established in 1993, aiming to return the deer into the wild. Adjacent to the reserve is China's finless porpoise reserve that shares the same waters with the deer reserve. The marshlands and reeds make it a perfect habitat for milu. Thousands of years ago, they ran wild in this area.

During the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), documents show that large numbers of the deer roamed the wetlands along the Yangtze River. And some were even raised in captivity for hunting.

Over-hunting, climate change and the shrinking of the wetlands meant the deer gradually disappeared from the wild. After a century living in captivity overseas, they have finally been returned to China and released into the wild.

"There are three wild herds in and outside our reserve. Milu can swim and run fast, so they always go from one herd to another," Li says.

There was only one herd living in the reserve's core zone. A devastating flood in 1998 inundated the reserve. Some escaped, swimming across the Yangtze River upstream to near East Dongting Lake. And some fled to a forest not far away from the reserve and survived there.

Inside the vast reserve, there were fewer than 30 workers. Li Pengfei was the first to conduct research on milu released in the reserve, starting in 1993.

Li patrolled the reserve at least twice a week, observing the animals' behavior and collecting information. He has saved five deer that were either deserted by their mothers or became lost from their herd.

In 1998, Li saved a deer from the flood that turned the reserve into a river. It was a baby deer that had been deserted by its mother during its escape. He named it Jiaojiao, and the little deer followed Li wherever he went for almost a year. But finally Li released Jiaojiao back into the wild.

Now Jiaojiao has given birth eight times, and shows no trace of human interference. Li is delighted.

"Although I felt sad when it left me, I really wanted it to go back to its herd and be accepted by its fellows," Li says.

The milu's colloquial name is sibuxiang, which translates as "the four unlikes" because they have a horse's face, deer's antlers, a donkey's tail and a camel's neck. French missionary Pere Armand David took the animal to Paris in 1866. It was the first time the wider world learned about this species of deer.

The number of milu around the world has surpassed 4,000. But it remains on China's endangered and rare species list alongside the giant panda.

"The milu population is large enough considering there were only 18 of the animals 100 years ago. What we care about now is returning them to the wild, so they're not still tied to the reserve," Li says.

The reserve's core zone can house at most 600 milu. But there are already about 500. The limited capacity sets a critical cap on the expansion of milu's population, Li says.

"Our reserve is like an isolated island artificially separated from the outside. Our ultimate goal is to let milu go wild outside the reserve and to live harmoniously with humans," he says.

What worries him for the final target is whether people will kill the deer and that there will be conflicts between humans and the deer when they are both struggling for their living space.

Cai Jiaqi has endeavored to increase people's awareness to protect milu for years. He says the protection awareness of villagers living nearby is decreasing, especially when the deer run from the reserve to the farmland nearby, trampling on crops and eating vegetables like carrots and cabbages. It happens when their food - water plants and grass - run low on the reserve.

Cai is concerned that people will kill the precious mammal under such circumstances.

In ancient China, milu were associated with a kingdom's power. They were often used as a metaphor for subjects in a kingdom. Emperors of different dynasties were fond of hunting them and eating the meat. Chinese traditional medicine claims milu are good for men's health.

The rarity of the animal and their use in medicine makes Cai and Li worry about how the deer will coexist with human beings. Killing the animal is punishable by jail, but the struggle for living space between man and deer is inevitable.

Years ago, miles of farmlands around the reserve were planted with reeds, says farmer Hu Shifang. Large areas of reeds provided good shelter for the animals and nurtured water plants for them to live on.

Hu and her family have lived in this area all their lives. The 60-year-old says she used to see milu on her farmlands. Several years ago, Hu started planting cotton in her fields because cotton makes more money than reeds. The other villagers followed suit.

Since cotton has taken the place of reeds, the marshes have been shrinking. The food for the deer is in shortage. It's a vicious circle, says Li.

"We're calling for more support from the government to give farmers subsidies. It's critical for the deer to go wild," Li says.

Contact the writer at dengzhangyu@chinadaily.com.cn.

Liu Kun contributed to the story.

|

A herd of milu wander around the marshlands in the Tian'ezhou Milu National Nature Reserve in Shishou, Hubei province. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 01/16/2014 page18)

Gorgeous Liu Tao poses for COSMO magazine

Gorgeous Liu Tao poses for COSMO magazine

Post-baby Duchess

Post-baby Duchess

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China seeks to calm US fears over missile

Doubt on Tokyo's diplomatic push

China Mobile and Apple 'tie the knot'

Russia battles terror before Olympics

China vows reform to curb corruption

Corrupt officials beware this New Year

Shanghai schools to close on heavily polluted days

Air China ups Houston-Beijing service to daily

US Weekly

|

|