'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

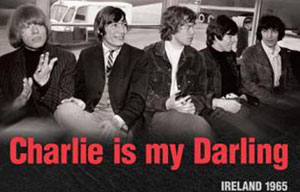

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Boom behind closed doors

Updated: 2012-08-05 08:02

By David Segal (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

Geneva

Simon Studer started his career in a basement vault in a warehouse complex near the heart of this city, known for international banks and outrageous prices. It was a strange job. Every day, someone would open the vault and lock him inside until it was time for lunch. Then he'd be let out of the vault and, after eating, he'd be locked in again until it was time to go home.

He was taking inventory for one of Switzerland's best-known gallery owners, who rented the space. "I was checking sizes, condition, looking for a signature," Mr. Studer recalls of his job 25 years ago, "and making sure the art was properly measured."

What was being tallied and assessed was the handiwork of Pablo Picasso. Thousands of pieces. It was Mr. Studer's first peek at the astounding wealth stuffed inside the Geneva Freeport, as this warehouse complex is known.

The second peek came when he realized what the guy in the vault next door was doing: counting a roomful of gold bars.

"That's the Freeport," says Mr. Studer, who now runs his own gallery.

Though little known outside the art world, this surprisingly drab series of buildings is renowned by dealers and collectors as the premier place to stash their most valuable works.

They come for the security and stay for the tax treatment. For as long as goods are stored here, owners pay no import taxes or duties, in the range of 5 to 15 percent in many countries. If the work is sold at the Freeport, the owner pays no transaction tax, either. Only once it exits the premises are taxes are owed, in the country where it winds up.

The Freeport is a haven where the climate - financial and otherwise - is ideal for high-net-worth individuals and their assets.

How much art is stockpiled in the 40,400 square meters of the Geneva Freeport? The canton of Geneva, which owns an 86 percent share of the Freeport, does not know, nor does Geneva Free Ports and Warehouses, the company that pays the canton for the right to serve as the Freeport's landlord. Swiss customs officials presumably know, but they aren't talking. There is wide belief among art dealers, advisers and insurers that there is enough art tucked away here to create one of the world's great museums.

"I doubt you've got a piece of paper wide enough to write down all the zeros," says Nicholas Brett, underwriting director of AXA Art Insurance in London, when asked to guess at the total value of Freeport art. "It's a huge but unknown number."

The number is about to grow. At the Freeport, construction has begun on a new, 12,000-square-meter warehouse that will specialize in storing art. It is scheduled to open at the end of 2013.

In the coming years, collectors and dealers will also have a variety of other high-security, customs-friendly, tax-free storage options around the world. Luxembourg is building a 20,000- square-meter freeport, scheduled to open in 2014 at its airport. In March, construction began on the Beijing Free Port of Culture at Beijing Capital International Airport. There has also been talk of doubling the size of the freeport in Singapore.

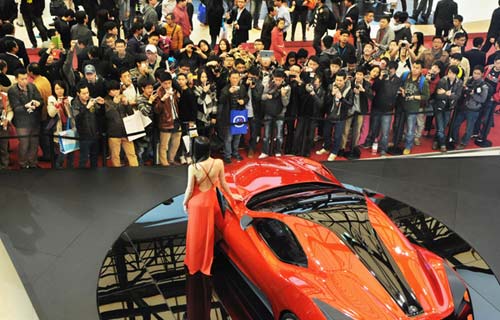

This construction boomlet is a novel way to gauge the art market's swift recovery from a precipitous fall in 2008, when sales at auctions, the industry bellwether, shrank in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Global sales in 2011, both at auction and in private deals, were estimated at $64.1 billion, according to Clare McAndrew, an art economist. That total is just shy of the record high of $65.8 billion set in 2007 - and well ahead of the 2009 trough of $39.4 billion.

In record time, the art market decline of 2009 has given way to new anxieties about overinflated prices. A major reason, Ms. McAndrew says, is the arrival of Chinese buyers in large numbers, as well as buyers from Russia and the Middle East. Then there is the newfound sense among collectors worldwide that art is a smart commodity to buy in the midst of economic turmoil.

"People have realized that art is a safe haven asset when other markets are doing poorly," Ms. McAndrew says. "In general, art holds its value over time, and in some cases it increases."

Deals at the lower end of the market are booming, too. Wendy Goldsmith, director of Goldsmith Art Advisory in London, describes a conversation with an artist who is "not museum quality," with eight pieces of newly produced art and a waiting list of 81 people. "What do you suggest I do?" the artist asked Ms. Goldsmith, a little desperately.

The lines for the marquee contemporary names are even longer. "I bought a Gursky for a client," Ms. Goldsmith says, referring to Andreas Gursky, whose stunning, large-scale photographs come with stunning, large-scale price tags. "I had to write Gursky a letter about my client's collection. I had to explain why my client wanted this photograph so much. And this piece cost over $1 million. It was like pledging your first born.

"The machinations are fascinating," she adds. "They're also spiraling out of control."

The difference between a room of Picassos and a stack of gold bars isn't what it used to be.

Some freeport users have been collecting for years, purely out of passion, and suddenly find that pieces they bought decades ago are now worth such immense sums they fear to keep them at home. More typical are collectors seeking storage and tax relief for purchases they never intended to display.

The Geneva Freeport sits about three kilometers from the center of Geneva, next to a post office and amid a hodgepodge of gray and unremarkable bridges and streets.

Media tours of the Freeport are rare, but there have been more in recent years as the government and the company that runs the facility strive to reassure the public that there is nothing unscrupulous going on here.

In part, this is a hangover from 2003, when Swiss authorities announced that they would return hundreds of antiquities stolen from excavation sites in Egypt. Some of the items were reportedly painted in garish colors so they could be smuggled in as cheap souvenirs.

The episode helped to spur some regulatory changes, including a rule that requires tenants to keep an inventory.

"The legislative changes were in response to the criticism," says Eva Stormann, an attorney in Geneva. "But much of that was based on a wrong understanding of how the Freeport works. It is a highly reputable place."

On a June afternoon tour of the Freeport, the first stop is a wine cellar piled high with crates stamped with names like Chateau Mouton Rothschild and Dom Perignon.

Art, it turns out, is just one category of valuable stored in these buildings. Cigars, Lamborghinis, soap and Porsches show up, too. There is also a silo large enough for about 40 metric tons of grain.

It's the last bit of evidence that when the original Freeport here opened back in 1888, it wasn't for rarefied assets at all. It was designed for agricultural goods, a brief stop in their transit from one part of the country to another.

But the upside of the "temporary exemption of taxes and duties for an unlimited period of time," as it's called, caught the eye of a more upscale crowd.

The concentration of so much great art has started to make insurers nervous. "The nightmare scenario is a plane crash, or a fire, or a flood," says Adam Prideaux, an insurance broker at Blackwall Green in London.

He adds that new policies for the Freeport are cost-prohibitive or impossible to write.

A handful of galleries have sprung up here, and the first, three years ago, belonged to none other than Mr. Studer, the dealer who once cataloged Picassos.

Why the Freeport? There is not a lot of window-shopping here because there aren't a lot of windows. Mr. Studer himself says: "It's nothing fancy, nothing sexy. It's just pure business. It's a very gray, very boring, dark, Swiss place." But when you go inside, he says, "you have some surprises."

Also, the rent is inexpensive when compared with that in downtown Geneva.

And, Mr. Studer says, "if a person is willing to come to the Freeport, they are serious about buying."

The New York Times

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|