'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

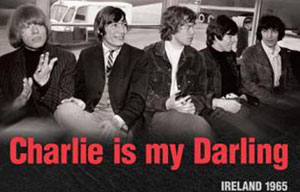

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Finding history in pages and spines

Updated: 2012-08-05 08:02

By Jennifer Schuessler (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

Jessica Pigza, an assistant curator in the New York Library's Rare Book Division, examined a leather book cover. Andrew Shurtleff for The New York Times |

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Virginia - For five weeks each summer Rare Book School at the University of Virginia brings some 300 librarians, conservators, scholars, dealers, collectors and random book-mad civilians together for weeklong intensive courses in an atmosphere that combines the intensity of the seminar room, the nerdiness of a "Star Trek" convention and the camaraderie of a summer camp.

Vic Zoschak, a retired Coast Guard pilot turned antiquarian bookseller from Alameda, California, took his first class in 1998 and has returned for 14 more. "Flying search-and-rescue missions was satisfying work," he said. "But here, I found my people."

For many, Rare Book School is an important networking opportunity. But it also fills an important intellectual niche, teaching skills and knowledge that have been orphaned by increasingly technology-minded library schools and theory-oriented literature departments.

Bringing an understanding of the materiality of the book back into literary studies is something that Michael Suarez, an Oxford-trained specialist in 18th-century British literature and a Jesuit priest who took over as the school's director in 2009, speaks of with an almost missionary zeal.

"A book is a coalescence of human intentions," he said in a phrase often repeated around the school. "We think we know how to read it because we can read the language. But there's a lot more to reading than just the language in the book."

The atmosphere at Rare Book School is casual and egalitarian, despite the presence on the faculty of some of the world's leading experts in the history of books.

Initiation into the complex particulars of book history is acquired in the school's lectures and lab sessions, where students learn to look past the words on the page to recover the moment when ink met paper. In a reading room on an upper floor of the university's Alderman Library one morning, students in Advanced Descriptive Bibliography were bent over books with tape measures and mini light sabers called Zelcos, scanning the pages for watermarks, lines and other clues that can potentially trace a given sheet back to a specific paper mold in a specific mill.

The goal of Advanced Des Bib is to reverse-engineer precisely how the pages of the book were folded, cut, printed and gathered.

But Rare Book School isn't just about pondering masterpieces of printing. What makes the experience unique, students say, is the chance to see - and touch - a huge variety of objects from the school's own 80,000-item teaching collection, including many that have been folded, stained, waterlogged, written in, worm-eaten or sometimes completely disemboweled.

"We're very interested in ways books are marked over time," said Barbara Heritage, the school's assistant director and curator of the collection.

In his opening remarks each week Mr. Suarez tells students that the purpose of Rare Book School is to acquire knowledge that will lead to wonder, which may then "incline toward love."

The New York Times

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|