'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

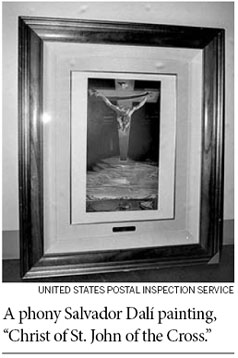

The art is fake, but it keeps on selling

Updated: 2012-11-18 07:59

By Patricia Cohen (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

As soon as Richard Grant, executive director of the Diebenkorn Foundation, glimpsed the three drawings in an apartment several years ago, he knew there was a problem. The works had been identified by the artist's estate as fake Richard Diebenkorns. But here they were again, proudly displayed as Diebenkorns by a new owner who had no idea he had bought discredited drawings.

The resale of fakes is a persistent and growing problem without a good solution, say collectors, dealers, artist estates and law enforcement agencies.

Although the Federal Bureau of Investigation can seize forgeries in criminal cases, these represent only a tiny portion of the counterfeit art that is circulating.

"They churn through the market," James Wynne, an F.B.I. special agent who handles art forgery cases, said of fakes.

There are no clear rules for what happens to phony art after it is identified. "It all depends what the facts are, what the art is, how many works are involved and how expensive they are," he said.

Art whose authenticity is disputed occupies a special limbo, as demonstrated by the settlement last month between Knoedler & Company, a Manhattan gallery that abruptly closed last year, and a customer who accused that gallery of selling him a forged Jackson Pollock for $17 million.

The F.B.I. is investigating whether that painting, known as "Silver Pollock," might be part of a larger cache of forgeries. But no charges have been brought and the gallery maintains that the work is authentic. So what happens to a $17 million painting that some people consider a fake?

When it comes to undisputed fakes, law enforcement officials try to halt resales by such practices as stamping works as fake or, in rare cases, destroying them, with the possibility of mistakenly destroying an authentic work.

Ultimately, though, both the police and buyers mostly rely on the art market to police itself.

Artist foundations and estates that find fakes on eBay or at small auction houses can inform the dealer or Web site, but they have no authority to seize or mark the work. Often, they say, counterfeits go underground and re-emerge later, labeled as the real thing.

In France, Switzerland and other countries that recognize the "moral rights" of an artist, heirs or foundations like Roy Lichtenstein's can ask the courts for permission to destroy a fake. But Ronald D. Spencer, a Manhattan lawyer and editor of the art-law handbook "The Expert Versus the Object: Judging Fakes and False Attributions in the Visual Arts," said the notion is "an anathema," noting how frequently opinions about authenticity can change.

Art experts and institutions, most prominently the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Lichtenstein Foundation, have stopped authenticating art, or pointing out suspected fakes, for fear of being dragged into a lawsuit by the owner of a work they rejected.

Major auction houses that discover an advertised work is fake usually cancel the sale and return the art to the seller. What happens afterward to these sorts of returned works is anyone's guess.

Once law enforcement is involved, forgeries may be stamped after a conviction or plea agreement, federal prosecutors in Manhattan said. Sometimes the work bears an F.B.I. evidence sticker.

"This makes the federal government an accessory to future art fraud," Bernard Ewell, a Dali art appraiser, said at the time. Then he added, "But I'm delighted because it gives me guaranteed job security."

The New York Times

(China Daily 11/18/2012 page12)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|