Asian Americans find their history

Updated: 2013-12-26 10:45

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

During the construction of New York City Chinatown's Confucius Plaza in 1974, the lack of Chinese representation on the building crew inspired an outpouring of protests within the community over the span of several months and eventually secured employment for about a dozen laborers. In the process, the young lawyers who helped defend the protesters were inspired to form the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, a community organization that exists to this day.

That momentum propelled the 20,000 people who marched on City Hall in 1975 to protest police brutality against a 27-year-old named Peter Yew. In an unprecedented move, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association shut down most of the businesses in Chinatown in solidarity, lending support to an Asian-American activist movement that had begun several years earlier and went on to indelibly shape Asian-American identity.

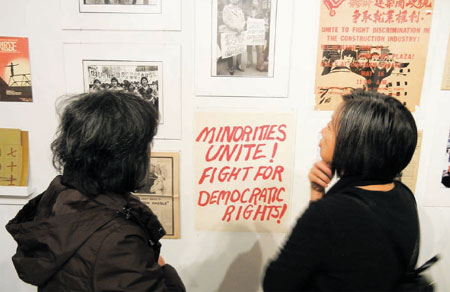

An assortment of ephemera related to that movement, including photographs and posters from both those protests, is now on display in Serve the People: The Asian American Movement in New York, an exhibition at New York's Interference Archive through Feb 23.

Featuring posters, newspapers, leaflets, political buttons and photographs related to what curator Ryan Wong calls a "constellation of organizations, individuals and actions", the exhibition presents a vivid document of Asian American activism and cultural production in the 1970s, spotlighting a history too often neglected.

"As someone with a lot of friends who are Asian-American activists and artists today, I can say that for many of us, it feels like we have no history," curator Ryan Wong said. "That history is lost or buried, and rarely included in text books. The reality is that there would be no Asian-American identity without the Asian-American movement, because it was a conscious group effort to define ourselves."

The Asian-American movement can be traced to the 1968 Third World Liberation Front protests at UC-Berkeley and San Francisco State College, in which Asian-American, African-American, Latino and Native American students banded together to demand the establishment of ethnic studies departments at both universities. Inspired by those protests, young artists and activists on the East Coast began organizing groups like the Basement Workshop, a facility that printed small publications devoted to giving voice to Asian-American poets, fiction writers, activists and artists, and provided a space for discussion.

"What people were trying to do at the time was invent the idea of 'Asian-American,' and understand what that identity could be based on politics," Wong said. "At that time, there was really no such thing as 'Asian-American' in the popular imagination; you either identified with your country of origin - mostly China, Japan or the Philippines - or you were called 'Oriental.' The Asian-American movement was the idea that we could have a voice, a way to challenge how we were seen in America and how we viewed ourselves, by organizing, creating art, theater, dance, music, and in pushing forward the development of community services that served immigrant communities."

Tomie Arai, an artist whose graphic design and illustration work is featured prominently in the exhibition, noted that positive depictions of Asian Americans in the mainstream media were rare if not non-existent at the time.

"I can't overstate how important I think archives are to the process of understanding the social history of the US and a collection of this kind of ephemera, which is not part of the mainstream historical narrative," Arai said. "It's incredibly important to people who don't see themselves represented. We were able to construct a different version of history, and of who we were."

Corky Lee, a photographer who documented the Chinatown protests in 1974 and 1975, estimates that around 60 percent of the active participants in the movement were American-born, with the remainder having immigrated to the US more recently.

Many of the movement's leaders were inspired by the political upheaval taking place in China and in the perceived wrongs of the Vietnam War, Wong said. Included in the exhibition are a number of reproductions of Cultural Revolution-era Chinese posters, as an example of both the graphic design and rhetoric that inspired some activists to question whether that level of intensity and revolution was possible in America.

And although a government revolution never came to fruition, the movement was a revolution in terms of the way Asian Americans identified, Wong said. The period was formational not only for many Asian Americans as individuals but for a number of still-existing community organizations.

"This isn't just an Asian-American story," Wong said. "This is a story of a whole era, when a generation of Americans started to rethink their relationship to history, to the government, and to America."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

|

Visitors to Serve the People: The Asian American Movement in New York, an exhibition spotlighting activism in the 1970s, stop before a sign calling for action. Kelly Chung Dawson / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 12/26/2013 page2)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Viacom-Sohu.com deal 'a foothold': analyst

Reform plans give US 'hope about trade'

Abe's shrine visit grave provocation

Abe to visit Yasukuni Shrine

US just passing the buck

Turk PM reshuffles cabinet

Asian Americans find their history

GDP growth to hit 7.6% this year

US Weekly

|

|