Olympic medal journey at London show

Updated: 2012-04-24 10:05

(Agencies)

|

||||||||

LONDON - From mines in the United States and Mongolia to the necks of the world's most elite athletes, a display at the British Museum investigates the journey of the 4,700 Olympic medals to be handed out in London this summer.

Four gold medals designed for the London 2012 Games glisten on display in an exhibition which details the history of all the gold, silver and bronze medals using shavings, ancient medallions, and original moulds.

The gold medals for this summer's Games will be the largest and most valuable ever to be handed out.

Weighing in at 400 grams - roughly the same as a can of baked beans - and measuring 88 mm in diameter, the 1st place medal is also the most expensive yet. But it is only made up of 1.2 percent gold.

The nationwide search for designers was launched three years ago, and a panel eventually whittled the names down to goldsmiths, David Watkins who designed the Olympic medal, and Lin Cheung, who is the brains behind the Paralympic medal.

While the design on the front is dictated by tradition - Nike, the Greek goddess of Victory, has adorned medals since the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam - the back offers a blank canvas.

Weaving the river Thames through the design, Watkins brings the medal up to date with a mixture of Greek mythology and images of London, achieving a lushly intricate feat of metal molding. But it wasn't always plain sailing.

At the Royal Mint, last minute technical problems with the gold stamps meant that the image of Nike varies ever so slightly from its predecessor at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

"There's not a lot of room for maneouvre there," explains Philip Attwood, curator of the collection. "But as I understand it, they had to reproduce the models for technical reasons...it was minor, just so the two sides of the medal worked with each other."

When it comes to pressing gold, such minor tweaking is much more than just small change.

Given pride of place at the top of the main stairs, more than 2 million visitors will pass by the four gold medals before they are returned to the Olympic governing body.

Hardly anyone passing by can resist getting a picture of themselves with the medals.

"I go past here each day, and there are always people, who, as soon as they realize these are the prize medals, walk straight up the stairs and start taking photos," Attwood said, as a gaggle of French school children sieze upon another tourist to snap them, beaming, and jostling for centre stage, posing as if they were winners themselves.

"The display was put up in September last year, to coincide with the launch of the London 2012 Paralympic medal...but we wanted to keep the medals there until the Olympics actually happened so we extended the focus," Attwood said.

"Originally the display was all about 2012, but now we have added in the historical context, and in particular the longstanding link between Britain and the Paralympic movement."

As keeper of the department of coins and medals, Mr Atwood is in charge of 70,000 medals in the British Museum collection - but even he knows it's not all about going for gold.

"I remember Peter Radford [Olympic runner and medallist] wrote about what he'd done with his medals and clearly he'd kept them all, but it was his earliest medals, when he first won a local competition - and they're pretty crummy medals - which were really important to him because they were the first ones he won."

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

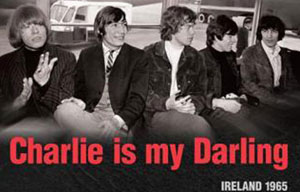

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

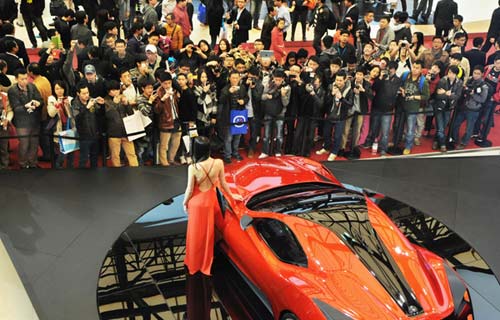

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|