Mining wasteland faces green challenge

Updated: 2013-11-05 07:20

By Wamg Kaihao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Little cause for optimism

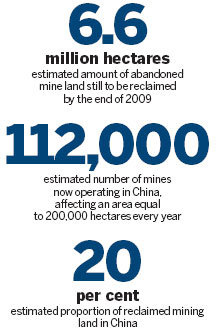

As early as 1989, the State Council, China's Cabinet, demanded that mining companies reclaim used land and return it to its natural state. The announcement was followed by a series of experiments in the industry, but the situation today is not a cause for optimism.

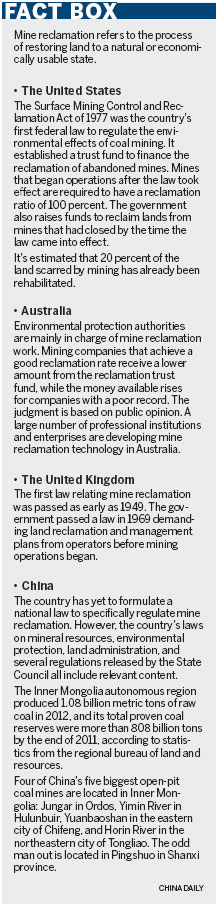

Liu Yanping, director of the land property office under the Ministry of Land and Resources, estimated that the current ratio of mining land reclamation is only around 20 percent, compared with approximately 80 percent in developed countries.

|

More than 112,000 mines are currently operating in China, affecting an area equal to 200,000 hectares every year.

The Ministry of Land and Resources announced in March that it aims to promote land reclamation in China's newly exploited mines by the end of 2015.

In 2011, when the State Council unveiled the Land Reclamation Rule, the ministry selected four mining areas, including Ordos, as experimental districts for reform of the approval and management procedures of land used for temporary mining and requiring greater supervision of mine reclamation. In Ordos, 80 mines are located in the experimental districts, and seven of them are in Ejin Horo.

These parcels of land, each less than 70 hectares, are transferred from the farmers to mining companies for two years. Once mining is completed, a three-year project begins to level the land and rehabilitate it. Once that work is completed, the land is returned to the farmers.

Since 2007, all mine operators have had to leave a deposit with the municipal government when they apply for mining licenses. The deposit can be as much as 150,000 yuan ($24,600) per hectare. When the mining work ceases, the deposits are only returned if the reclamation work meets national standards.

"If they (the operators) fail, we use the money to employ professionals to do the work instead," explained Song.

According to Bian Junmei, head of the banner's land reclamation center, the reclamation ratio in Ejin Horo was close to zero in 2007, the only exceptions being two large mines where measures were employed to minimize the hidden danger of land collapse. Bian said the reclamation rate is now 50 percent.

However Song is still uneasy. "Plants grow quickly in the mining areas of southern China because of the fertile land and abundant rainfall," he said. "It's a different scenario here. We can't just rely on the power of nature. We need more human intervention."

A common practice in mine reclamation in Ejin Horo is to cover the leveled land with a thin layer of earth, usually 0.5 to 1 meter deep, and then plant grass later. However, despite the healthy appearance, the land is now barren.

"Once the land has been fully exploited, the mining companies don't want it anymore," said an embarrassed Song. "The farmers no longer want the land either, because it's too barren to be recultivated. It costs too much to maintain the grass. Technically, this is just wasteland."

A promising experimentNevertheless, some districts have made great efforts to ensure a decent future for the reclaimed land.

Fifty kilometers from the banner seat and covering an area of 9.18 sq km, Wujiata is one of the biggest open-pit coal mines in Ejin Horo.

When we visited, the locals were busily harvesting vegetables on the farmland beside the mining pit.

"We don't need to buy vegetables from outside and we even have a surplus supply for the neighboring mines," said Zhang Tingbang, head of the Wujiata mine's technology department.

The 10-hectare fields have been reclaimed, and the crops being sewn on them include sunflowers, corn and wheat.

According to Zhang, the operators of the mine, which began operations in 1996, made efforts to prevent a troubled ecological aftermath.

"Abandoned mining land can easily become deserted and that influenced our production regime," he recalled. "We had to spare so much effort to level the terrain and plant sand dune willow to prevent sandstorms, but our role was mostly passive."

In 2004, a project was launched to restore the ecological balance. It has since progressed slowly through a process of trial and error.

"It takes a decade to gradually ameliorate barren land via sheep compost," said Wang Wensheng, a mineworker who was harvesting eggplants in the field. "We are lucky that rainfall has become slightly more abundant in the last two years and we are finally beginning to see results."

Drought is another factor hampering restoration of the ecosystem.

"We tried to use spray-irrigation on the fields, but it didn't work well and the equipment was very costly," said Wang. "We now combine several water-efficient irrigation methods and the crops are growing better."

Trees cover 85 percent of the 600 or so reclaimed hectares of land, but Zhang admitted the ecological project has no economic return.

"We can probably open tree nurseries and form a green industry in the future, but all the work we've done up to now was to improve the appearance of the landscape. That only earns social benefits, but it's good to do something in the public interest. It will also help our business, especially because coal isn't selling well now," he said.

Not talking trash

Not talking trash

Training begins for weapons destruction

Training begins for weapons destruction

Police detain swimming star for driving SUV without license

Police detain swimming star for driving SUV without license

Nongfu Spring accuses Beijing Times of defamation

Nongfu Spring accuses Beijing Times of defamation

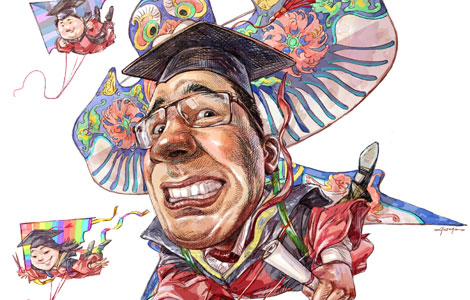

Movie director Feng leaves a lasting impression in Hollywood

Movie director Feng leaves a lasting impression in Hollywood

Egypt's Morsi arrives at court for trial

Egypt's Morsi arrives at court for trial

Rare solar eclipse 2013

Rare solar eclipse 2013

New York City Marathon concludes in chills

New York City Marathon concludes in chills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

White House dismisses Snowden's clemency plea

Wall Street Journal wades into dispute

Merkel says US ties must not be put at risk

Xi calls for targeted policies to fight poverty

Separatists spreading skills over Net

New warning on overcapacity

Strong IPO lineup on US bourses

New ideas urged on Taiwan issue

US Weekly

|

|