Movie mogul Run Run Shaw, 107, dies in HK

Updated: 2014-01-08 08:14

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Raymond Zhou reports on the life and times of a workaholic star-maker and philanthropist.

Run Run Shaw, media mogul and philanthropist, died at his home in Hong Kong on Tuesday morning.

Arguably the greatest and longest-operating force in Chinese-language film and television, Shaw was 107, according to the traditional counting method used in his hometown.

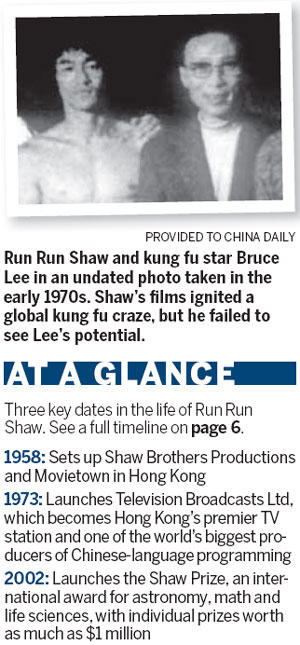

He was instrumental in maneuvering the Chinese film industry from silent movies to talkies, from black-and-white to color, from talking to singing and dancing, and from a female-dominated genre to a male-dominated kung fu fight fest.

He later switched from movies to television.

In his personal life, Shaw evolved from counting the pennies to lavishing his money on worthy causes, such as education and healthcare.

His longevity was matched by his industry and dogged commitment to the rules. His populist aesthetics kept him in touch with the grassroots a lot of the time and his movies reinforced traditional Chinese values, rather than blazing new trails or conquering new frontiers.

Shaw's career spanned many decades. He started in movie distribution and exhibition before moving into production, turning himself into the biggest film producer in the Chinese-speaking world for a long period.

When his movie industry career began to slip, he found a new realm in television, and his influence is still felt today, along with the stars he minted.

For an emerging generation in China that has never heard of Shaw's contribution to the country's cinema, his name often features prominently on the buildings where they absorb knowledge, a testament to his enormous generosity to educational and other charities.

Younger sibling

Run Run Shaw began his movie career doing odd jobs for his elder brothers' company, the equivalent of a mailroom clerk in Hollywood, but with a much more versatile role. He had just finished high school at an US-run establishment in Shanghai and his father expected him to go on to college. But Shaw seemed to love what he was doing at Tianyi Film Co, rotating through every job, including scriptwriter, actor, director and, finally, cinematographer, a role in which he excelled.

Run Run's eldest brother founded Tianyi in 1924. The company quickly grew into one of the top three film studios in Shanghai through its adaptations of Chinese folk tales that reinforced traditional moral values, which ran counter to the enlightenment movement of the day. This populist strategy in subject matter continued through all the ensuing incarnations of the brothers' entertainment empire.

In 1926, six major studios formed an alliance to boycott Tianyi. Distributors that wanted to show movies made by the six studios had to agree not to show anything from Tianyi. Partly to deflect the competitive pressures and partly to forestall the possible fires of war from the north, the Shaw brothers decided to explore the market in Southeast Asia, where there was a sizeable ethnic Chinese population. The 19-year-old Run Run and older brother Runme were sent to negotiate with cinema owners and companies.

The two brothers pleaded with exhibitors to show the prints they had brought with them. They rented a horse-drawn carriage and toured the rural areas. Their hard work paid off; soon they were buying up cinemas. The first few years in Southeast Asia, known as the South Seas in China, "gave me so much that was of benefit for the rest of my life", as Shaw later recalled. One of the explanations for his English name, Run Run, comes from that period, when the young man ran around endlessly in his attempts to start a business from ground up. A different explanation, which he endorsed, is the phonetic similarity of Run Run and Renleng, his real given name.

Success allowed Tianyi to shift production to Hong Kong when Japanese bombs began to fall on Shanghai in 1932. Run Run's insistence on adopting sound technology - he made a perilous trip to San Francisco to purchase equipment - resulted in one of the first Cantonese-language films, The Platinum Dragon. The movie was a blockbuster and paved the road for the Shaws' expansion.

The backbone of their business was still in distribution and exhibition across Southeast Asia and by 1939, they owned 139 movie theaters in the region. Their movie empire was eventually crushed by the Japanese invasion of Asia.

Hong Kong legend

Run Run Shaw was aged 50 when he moved permanently from Southeast Asia to Hong Kong. Dissatisfied with his older brother's management style, the younger man bought him out, including the purchase of more than 74,320 square meters of land in Clearwater Bay.

In 1957, Run Run put his big dream to work. He launched Shaw Brothers Productions and broke ground in a seemingly remote suburb, constructing Movietown - a vertically integrated all-in-one facility that was clearly modeled on a Hollywood studio. The studio took seven years to come to completion, with 1,500 employees and four soundstages in the first phase. Everything required for movie making, other than the negatives, could be achieved on the premises.

As with Tianyi in Shanghai, the Shaw Brothers encountered fierce competition from other studios, especially Motion Pictures & General Investment Co, known as MP&GI.

The two studios would wrangle for talent, but their fights over the same stories were even more spectacular. When Shaw heard that MP&GI was making The Butterfly Lovers, which had a plot similar to Romeo and Juliet, but was based on a folk story, Shaw rushed his own version into production and finished it in just two weeks. Not only did Shaw steal his rival's thunder, but he created a runaway hit entitled The Love Eterne, which has acquired a similar stature to that enjoyed by Singin' in the Rain in Hollywood.

Shaw reached a compromise with MP&GI in March 1963. Three months later, Loke Wan Tho, the owner of MP&Gi, and his lieutenants were killed in an air accident in Taiwan, essentially leaving the Shaws as the only major players in the Hong Kong film industry.

Run Run Shaw started two trends that left indelible imprints on Chinese-language cinema by grooming two unknown genres into pioneers and giants. The first was female-dominated musicals, with Diau Cham (1958) as his opening salvo. Director Li Han-hsiang took two strands, traditional Chinese opera and the Hollywood musical, and fused them into a unique genre that swept the Chinese-speaking world (other than the Chinese mainland, which remained closed to all imports, apart from a handful of government-controlled productions).

When the musicals started winding down in the late 1960s, Shaw gave a directorial opportunity to the erstwhile film critic Chang Cheh to make the kind of movies he had dreamed of. The result was a spate of martial arts films, starting with One-Armed Swordsman (1967), which were so revolutionary they completely upgraded the genre, and the ripple effects are being felt even today.

Studio system

Shaw followed a studio system that employed talent at a time when the Hollywood studio system was disintegrating and beginning to use agency-based talent. He signed long-term contracts with newcomers, but refused to let them share the profits from huge hits. This strategy helped him to control costs but was also the cause of major talents, such Li Han-hsiang, leaving him - after Li had found fame. Shaw sued, but when Li failed to launch his own film business in Taiwan, Shaw took him back, a move uncharacteristic of Chinese employers.

As the global film industry moved away from the rigid employment system, Shaw's way of doing things resulted in missed opportunities and the loss of many talented individuals. When Bruce Lee returned to Hong Kong to begin his film career, he approached Shaw first and asked for $10,000 for a picture. Shaw wanted to reduce the actor's fee by 75 percent, and he was offended that an untested newcomer had the chutzpah to name his own price. In an about turn, Lee joined another studio, Golden Harvest, which had just been founded by Raymond Chow, a long-time Shaw lieutenant. The rest is history.

Shaw had lured Chow from journalism in 1959, and groomed him to be his right-hand man. However, when Shaw hired Mona Fong, a singer popular in Southeast Asia at the time, Chow sensed he was being sidestepped. He founded Golden Harvest in 1970 and quickly became Shaw's biggest competitor. While working for Shaw, Chow's laissez-faire management style provided an antidote to Shaw's more hands-on approach and was more in line with the trend for so-called independent productions.

In the 1970s, Shaw enjoyed bouts of successes, such as Li Han-hsiang's erotic genre and historical movies set during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Generally, though, Shaw's film business was going downhill, and market share shrank from 60 percent in the company's heyday to just 10 percent. The film production unit all but folded in the mid-1980s, only producing the occasional film every few years.

Hong Kong's film industry enjoyed one more decade of boom and glory, but Shaw was not part of it. However, Shaw Brothers made news in 2000 when it sold a film library containing almost 800 titles to Celestial Pictures for $84 million. Celestial digitally refurbished the movies and released them via channels such as DVD and television.

TV dominance

If Shaw misjudged the final golden age of Hong Kong cinema, he was prescient about the dawn of the television business. As his influence in movie production waned in the late 1970s and early '80s, his investment in Television Broadcasts Ltd grew constantly. Eventually, he became the largest shareholder and, in 1980, when the original owner died, Shaw assumed control and turned TVB into the world's largest privately owned producer of Chinese-language TV content.

Shaw leased his own vacant film production facilities to his television production company. He employed his old strategies, such as programming self-produced content and rarely buying shows from outside sources. Again, the management of cost and talent was his forte, and the policy of preemptive strikes first used in 1930s Shanghai and perfected in the 1960s was once again employed. When rival ATV was making a series about Genghis Khan, TVB jumped ahead with its own version. Unlike the film market, Shaw's TV dominance has never been challenged in Hong Kong, and TVB has enjoyed market share as high as 80 percent throughout much of its existence.

One byproduct of his TV empire are the big-name stars that have towered over Chinese-language cinema in recent decades. Luminaries such as Chow Yun-fat, Andy Lau, Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Stephen Chow are all graduates of Shaw's TVB actor training classes, while others, such as Maggie Cheung, Leslie Cheung, Jacky Cheung and Leon Lai, were discovered in singing contests or beauty galas organized by TVB, a veritable star-making machine only rivaled in the Chinese-speaking world by the State-owned China Central Television, and then only during the past decade.

Philanthropist

Shaw's work ethic is often credited as the main reason for his success. For much of his life, he worked 16-hour days. He would watch the "dailies" of every film in production and write his feedback on a sheet of paper. He would review every story and script under development. He said his entertainment was the same as his job, which was watching movies. Unverified reports suggest that he had watched more movies than any other person alive. Before the age of 80, he would view 600-700 feature films every year - his record was nine movies in a single day.

He said he watched all kinds of movies to understand the zeitgeist and know what was popular at the time. He would judge a project by its box-office potential and would never become involved for purely aesthetic reasons. When directors made money for him, though, he would grant them greater leeway in terms of subject matter and budget.

Shaw's rigidity in employee compensation was in sharp contrast to his spendthrift ways in philanthropy. In 1973, he launched a charity foundation with the emphasis on education. "China has poverty and needs lots of money to develop education," he once said.

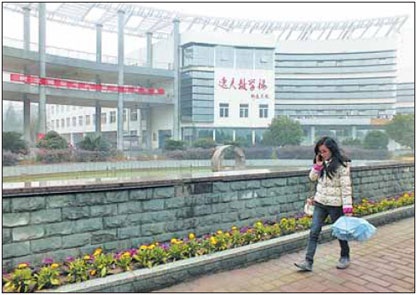

More than 5,000 buildings on the nation's college campuses bear Shaw's Chinese name, "Yifu", which he took as an adult. His brothers also adopted new names.

Now, students are so accustomed to seeing "Yifu" that many believe it to be a generic name for a building.

Shaw's donations to the world of education were not limited to the Chinese mainland, but also spread to Hong Kong and the Western world. Universities such as Harvard, Stanford, MIT and Oxford have all benefited from his money.

Another recipient of his largess was the medical sector. Again, that's evident from the names of many hospitals and individual buildings. Shaw also gave large amounts for the protection of cultural heritage sites such as the Dunhuang Grottoes.

In 2000, Shaw launched an ambitious award for the scientific community, providing $1 million for each of three award categories deemed neglected by the Nobel Prize.

Shaw had four children: Vee Meng, So Man, So Wan and Vee Chung. He married Mona Fong in 1997 when he was 90, 10 years after his first wife, Wong Mei Chun, also known as Lady Lily Shaw, passed away. He thought that it was the "right thing to do" for both women.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

|

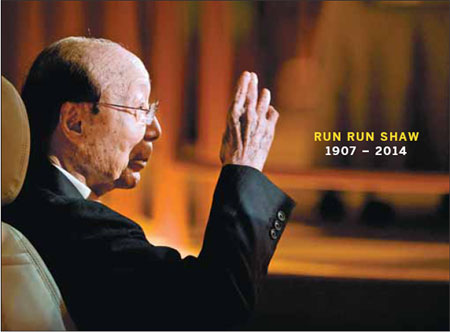

Movie and television producer Run Run Shaw attends the Shaw Prize presentation ceremony in Hong Kong on Sept 28, 2010. Shaw, 107, died on Tuesday. Wen Di / for China Daily |

|

Miss Hong Kong Pageant 2005 1st runner-up Sharon Luk poses with Run Run Shaw, veteran producer and founder of Shaw Brothers Studio, at the Miss Hong Kong Pageant 2006 in Hong Kong. The pageant, which became a permanent TV fixture in 1973, is one of the Hong Kong institutions spawned by TVB. Paul Yeung / Reuters / Files |

|

This 'Yifu' building at a campus in Yichang, Hubei province, is one of the 5,000 buildings on the nation's college campuses bear Run Run Shaw's Chinese name. Many students are mourning him. Liu Junfeng / for China Daily |

|

Run Run Shaw receives a birthday present of a golden peach from Hong Kong actresses during the TVB 34th Anniversary Special in Hong Kong in 2001. Kin Cheung / Reuters / Files |

|

Clockwise from top: Stephen Chow, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Jacky Cheung, Chow Yun-fat, Andy Lau, and Maggie Cheung are a few of the A-list stars minted from TVB acting classes or shows. |

(China Daily 01/08/2014 page6)

Pollution's effect on health not clear yet, officials say

Pollution's effect on health not clear yet, officials say

Russia imposes security clampdown in Sochi before Olympics

Russia imposes security clampdown in Sochi before Olympics

X-ray reveals crying toddler had 5-cm needle inserted in his lung

X-ray reveals crying toddler had 5-cm needle inserted in his lung

Tokyo urged to end militarism

Tokyo urged to end militarism

Military drill in SW China

Military drill in SW China

Rodman in DPRK with ex-NBA team

Rodman in DPRK with ex-NBA team

Merkel breaks pelvis

Merkel breaks pelvis

Trick photography

Trick photography

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Odierno: US, China to work on issues

China is importing more US-built cars

Reform plan faces `challenges’: Professor

US jobless bill clears Senate hurdle

Solar firms face 'total eclipse' in US

Hong Kong Media mogul Shaw dies

Tokyo urged to end militarism

FBI names arson suspect

US Weekly

|

|