Unwilling guests of the Emperor

Updated: 2014-04-21 07:30

By Gao Anming, He Na and Wu Yong (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

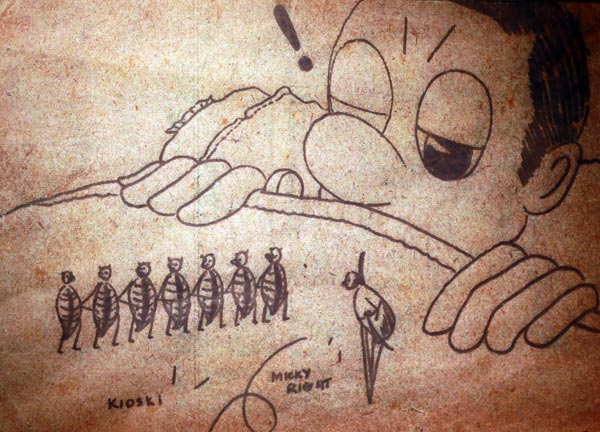

| An illustration by William Wuttke depicting life in the camp. |

From one hell to another

|

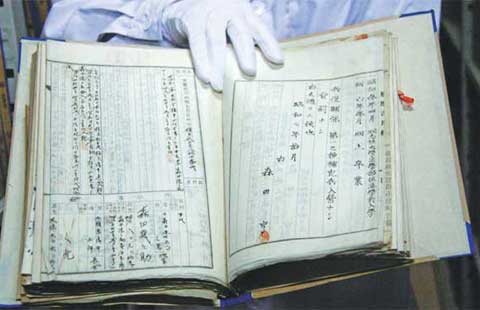

There are many ways to record history. Because writing was prohibited in the Mukden camp, the POWs stole paper on which they drew cartoons through which they vividly recorded life in the camp and made scabrous attacks on their Japanese guards. Three of the prisoners - Malcolm Fortier, Barton Pinson and William Wuttke - worked in the camp's draftsman's office shop, which provided them with access to materials. They quickly become known as the camp's main artists. The three worked clandestinely to avoid drawing attention to their work, which they concealed under their clothing to escape detection. Some of their work can be seen in an exhibition of cartoons at the camp museum. In one illustration, Wuttke drew himself lying beneath a blanket, watching fleas lining up and saluting. In the camp, prisoners were forced to stand and salute the Japanese soldiers. Those who forgot or refused to do so were beaten. In the eyes of the prisoners, even fleas were forced to stand to attention and call out their identity numbers. Hopes of surviving and being reunited with their families provided crucial moral support for the prisoners, who blocked out the mundanity of camp life by thinking of their loved ones back home. -He Na |

The first batch of POWs arrived on Nov 11, 1942. They were originally held at a temporary camp in Beidaying, a former Chinese army barracks, before being moved to Mukden and two satellite camps in July 1943.

Mukden camp, which covered an area of 50,000 square meters, consisted of three barracks and a few other buildings, most of which were demolished after the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949.

The memorial is only one-fourth the camp's original size, and the surviving buildings and ruins have an air of sadness.

Fearing that the POWs might escape, the Japanese topped the walls with high-voltage wires and set searchlights and machine guns in the watchtowers, which were manned 24 hours a day.

The only surviving barracks, a small, two-story building that housed 640 prisoners, still has its original facade.

"There were just a dozen toilets for about 2,000 people. The sanitary conditions were terrible and various infectious diseases swept the camp," Jing Xiaoguang, director of the Shenyang 9.18 Historical Museum, said.

In his book Rice, Men, and Barbed Wire, Arnold Beckael wrote: "Sleep is the opiate of POWs. When our eyes closed in slumber, we re-entered old worlds and familiar places. You could go back home and eat another of Mom's great meals ... and most of all, escape from the reality which is now,"

According to Jing: "Ten Russian-style stoves were installed, but they were cold most of the time because the Japanese were reluctant to provide enough coal. The temperature could fall as low as -40 c. Diseases and the cold led to the deaths of many POWs in the first winter. Digging graves was impossible because the ground was frozen, so the Japanese decided to abandon the work until spring. The corpses were all stored in a large room the POWs had to pass through every day on their way to eat."

The hunger was a nightmare, recalled Ralph Griffith from the US when he revisited the camp in 2007. "We had terrible food that even pigs wouldn't eat, but there was never enough of it."

A cartoon drawn by one of the prisoners depicted how the POWs ensured the equal distribution of rations by using a rule to measure each tiny piece of bread.

"The prisoners searched for anything to fill their empty stomachs, including wild vegetables and earthworms. They even caught wild dogs, birds or chickens that accidentally entered the camp," said Jing.

"Even so, they were still optimistic. They continued to exercise, and even formed a soccer team. One prisoner made a cello from wooden debris and boxes. To keep up their spirits, they often gathered to chat about the good food their mothers or wives made," he said.

Bacteriological tests

|

A friendship forged by food and fear First Person | Li Lishui Editor's note: Li Lishui was an apprentice at MKK. He told He Na about his experiences there. Concerned that the Chinese would help the prisoners, the Japanese ordered the POWs to work in the northern section of the factory, while the Chinese worked in the south. Talking and the use of hand gestures were banned. Anyone that contravened the rule was beaten heavily. On many occasions, I saw POWs pick up food we had inadvertently dropped on the ground. I often saw one particular POW, number 266. A small kitchen provided the food for the Japanese. One day, I found a small trolley stacked with vegetables. The Japanese didn't keep close eye on the apprentices, so one of the other apprentices and I stole some tomatoes and cucumbers. Just as we were eating them secretly, I saw POW 266 looking at me. Without thinking, I grabbed two cucumbers and threw them to him. He was very smart - he smiled at me and hid the cucumbers under the machine at which he was working. A few days after the camp was liberated in 1945, I met 266 at the gates of MKK. He gave me a handful of sticky black blocks and said something I didn't understand. I thought he had given me candy, but the sweets tasted bitter. Many years later I learned that it was chocolate. I didn't tell that story to anyone for about 60 years, but in 2002, a historian contacted me and handed over a letter and a photo. They were from prisoner 266, whom I then discovered was called Neil Galliano. In 2005, the United States government presented me with a certificate to thank me for the help I gave the prisoners. It was a proud moment. Li Lishui spoke with He Na. |

In the middle of the yard is a wall built from the bricks of a demolished barracks. The names of all those who died in the camp are scratched into the surface.

"The death rate at Mukden camp was much higher than at camps under German supervision. More than 300 POWs died," Wang said.

The POWs often fell sick without reason. As a result, the prisoners were forced to receive "vaccines" and physical checks.

In his diary, Major General Robert Pitty wrote that from January 1943 to March 1945, the prisoners were given more than 80 "vaccine" injections. These "preventative" moves failed to control the contraction and transmission of diseases, and the number of deaths rose.

"All of this was connected with a mysterious medical team from Unit 731, Japan's notorious biological corps. The team not only conducted bacteriological tests on the POWs, but also dissected the corpses and performed tests on their organs," Wang said.

The unit commander later admitted that they tested beriberi, pestis and cholera on the prisoners - 90 percent of those who died as a result were US nationals.

"The POWs were forced to count off in Japanese every morning and night, and to salute the Japanese soldiers whenever they passed," museum director Liu said.

The prisoners were insulted and beaten without warning.

"It is an atrocity. Atrocities I have never heard of before. Assault is a regular thing. People no longer treat it as something rather unusual," wrote Major Robert Petey, a British POW, in his diary.

He also wrote that the men were regularly made to stand with their arms outstretched, holding a bowl of water. If they spilled any of the liquid, they were beaten with a "kendo stick" or wooden sword. Prisoners were also made to hold their arms above their head, while bending at the knees. When their muscles tired and they could no longer hold the position, they were beaten on the backs of their legs.

Chinese help

"The POWs worked in a machinery factory called MKK, which was an important manufacturer of weapons and parts for Japanese aircraft," said Liu, the museum director.

"About 1,000 Chinese workers also worked at MKK. They often brought food and cigarettes for the prisoners, even though their living standards were no higher. The POWs stole goods and asked the Chinese to exchange them for necessities from outside," he said.

"The POWs were very tall, but very thin, with big deep-set eyes," recalled Li, the former apprentice.

"They started to work at 7 am. In winter, it was still dark at that time. They left at 6 pm, after sunset, so they often went several days without seeing the sun. Except for those who were seriously ill, all the POWs had to work," he said.

"However, the close connection stopped in spring 1943 after three escaped POWs were recaptured and executed. The Japanese believed that a Chinese worker had helped them, so we were divided into two working groups - we weren't even allowed to use the same toilets or look at each other," he said.

'Lost time'

A six-strong rescue team flew to Mukden camp in August 1945, shortly after the Japanese surrender. Team member Hal Leith wrote in his memoirs: "They circled me and asked many questions. I had never met people who were so happy. 'What about the Superbowl? Is Shirley Temple still alive?' They kept asking and asking."

In the past two decades, aware that time was not on their side and anxious that more people should know the history of Japan's wartime actions, some former POWs wrote memoirs and visited the camp.

"The history of Mukden is an important part of World War II that should be never forgotten. It shows Japan's cruelty and its ambition to dominate the world," said Wang.

Contact the writers at hena@chinadaily.com.cn and wuyong@chinadaily.com.cn

Liu Ce and Han Junhong contributed to this story.

Obama roasts himself, rivals at dinner

Obama roasts himself, rivals at dinner

Forum trends: No house, no marriage?

Forum trends: No house, no marriage?

Huge mist cannons attract people in Lanzhou

Huge mist cannons attract people in Lanzhou

Indian train derailment kills at least 12

Indian train derailment kills at least 12

One handed climber scales UK's toughest routes

One handed climber scales UK's toughest routes

World leaders when they were younger

World leaders when they were younger

H&M promotes summer collections with DJ show

H&M promotes summer collections with DJ show

Getting a taste for the World Cup

Getting a taste for the World Cup

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Travel passes to DPRK made easier

Yunnan's only panda perking up thanks to TV

Intl cooperation to aid drug fight

Deal signed to upgrade roads, grid in Ethiopia

China busts foreign spy ring

Tokyo lawmakers begin China visit

Houston tries shuttlecock diplomacy

Senior Chongqing official investigated

US Weekly

|

|