Migration adds to elderly-care woes

Updated: 2015-10-22 10:47

(Xinhua)

|

||||||||

|

|

Tan Lingeng, 76, together with his two grandchildren, pulls a flat-bed trailer loaded with straws for home in Tanjia village, Luoxi town, Jinxian county, Nanchang of East China's Jiangxi province, on July 22, 2015. Tan and his wife live with their eight grand children in the village as all their children have gone into cities to earn a living. [Photo/IC] |

A Chinese proverb advises, "rear children to provide for old age." Despite this, many parents are finding themselves living alone, without the companionship and care of their offspring.

Wang Zirong, 78, is a widow and mother of four, yet, she lives alone, a victim of the migration of hundreds of millions from the countryside to the cities.

None of Wang Zirong's children remained in Shishan village, Jiangxi province, to care for her. In fact, like many grandparents in rural China, she cares for her "left-behind" grandchildren, two teenage boys.

In a few years, these boys will also leave Wang Zirong, too.

"I have not dared think about what will happen to me when the boys go," she said. This a common concern for the rural-elderly population.

For rural migrants, few can host their elderly parents in what are often small, rented rooms, and most public nursing homes in the countryside will only accept people without offspring.

In response to this situation, the central government has pledged to build more nursing homes across the country.

Minister of Civil Affairs Li Liguo said in March that the government was planning to increase the number of nursing beds for the elderly from 26:1,000 to 40:1,000 in the years up to 2020.

Seeing the potential, private capital is also beginning to flow into the geriatric-care sector.

FLOATING ELDERLY

Compared with Wang Zirong's uncertain future, those that have the opportunity to live with their children in other cities count themselves lucky. But this arrangement is not without issues either.

Wang Xiuqin, 64, lives with her daughter in Jinan, capital of the eastern province of Shandong, hundreds of kilometers away from her hometown of rural Binzhou.

She is responsible for the day-to-day care of her grandson. For her, she finds babysitting as hard-going as farm work and she often feels isolated.

"I have no friends and nothing to do," she said. "Not only that but I find myself stepping on egg shells at home, afraid of saying something that will impact on my daughter's relationship with her husband."

The medical system has also yet to adjust to this "silver-haired" migration.

Although they can receive treatment in their new regions, medical expenses can only be reimbursed in their hometown, meaning extra expenses, and inconvenience.

"This has brought us a lot of trouble and I hope the system is fixed soon," said Zhang Yongfeng, a native of Xinxiang, Henan province, who is currently living in Jinan.

By the end of 2014, the number of the Chinese old people above 60 years old was 212 million, about 15.5 percent of the country's total population. The number is expected to reach 480 million by the end of 2050.

- New rules separate CPC discipline from the law

- HIV-infected parcels found in Beijing's delivery system

- Upper level SSAT scores cancelled in China administration

- Authorities investigate mainland visitor's manslaughter in HK

- Top leadership expected to discuss high-level vacancies

- Nude photos of kindergarten kids cause outrage

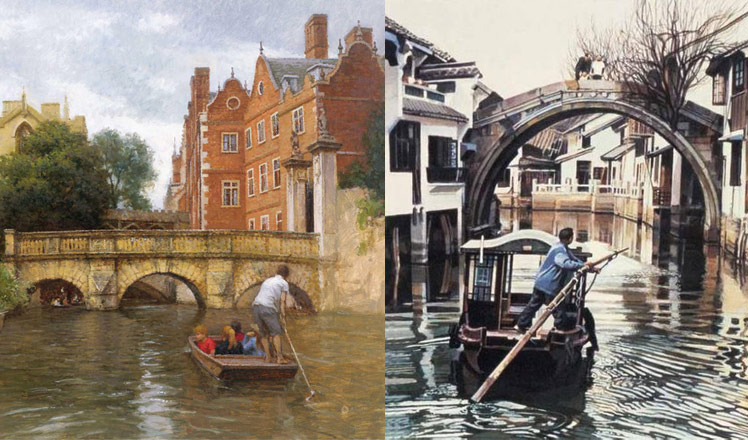

China and UK in the eyes of each other's painters

China and UK in the eyes of each other's painters

President Xi, first lady Peng attend Guildhall banquet in London

President Xi, first lady Peng attend Guildhall banquet in London

President Xi visits Imperial College London

President Xi visits Imperial College London

Peng visits Fortismere School in London

Peng visits Fortismere School in London

A tale of two countries – Chinese footballers' British struggles

A tale of two countries – Chinese footballers' British struggles

Top 19 Chinese CEOs accompanying Xi to UK

Top 19 Chinese CEOs accompanying Xi to UK

Royal toast: Queen hosts state banquet for visiting Xi

Royal toast: Queen hosts state banquet for visiting Xi

Xi and first lady visit British royal collections' Chinese items

Xi and first lady visit British royal collections' Chinese items

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

Xi pledges $2 billion to help developing countries

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US to accept more refugees than planned

Li calls on State-owned firms to tap more global markets

Apple's iOS App Store suffers first major attack

Japan enacts new security laws to overturn postwar pacifism

US Weekly

|

|