Chinese look at assisted-living homes

Updated: 2015-11-03 11:08

By Amy He in New York(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

When Aegis Living broke ground for its new Asian culture senior housing facility in Washington state, it was a near 100-degree day in July, and CEO Dwayne Clark expected no more than a handful of people in the audience.

Instead, more than 300 people showed up, including former US ambassador to China Gary Locke. "There was that much interest in that kind of program," Clark said.

The $50 million facility in the town of Newcastle 12 miles outside of Seattle isn't set to open until 2017, but interest in the retirement home from both the local Chinese community and abroad has been immense so far, he said.

Aegis Living, a housing chain with two-dozen assisted-care facilities across Washington state, California and Nevada, doesn't usually receive room deposits until facilities are one or two months away from opening, Clark said, but the Newcastle facility began receiving deposits from local community members four years before the groundbreaking and is already about 15 percent pre-leased.

"Our Cantonese- and/or Mandarin-speaking staff will provide care assistance 24 hours a day, safety and security systems, a licensed nurse, transportation and daily social activities," says Aegis' website.

There is an upfront fee of anywhere between $12,000 to $50,000 for the rooms, and then a monthly sum for rent and care, which could be about $4,000 to $8,000 a month, though the figure varies depending on the level of care and may be subject to change in the two years before the facility opens, Clark said.

Since the project's announcement, he said there has been an "exaggerated" level of interest from China, with buyers expressing interest in buying out the entire project or looking at the project as a safe harbor to invest their money in.

"I had one guy who said, 'Can I buy into the project?' "No, you can't buy into the project, but you can put a deposit down." He goes, 'What if I pre-paid you three years of my mom's rent now?' I said, "Why would you do that?" and he goes, 'If there is a rent increase, I would at least get the benefit of not getting those rent increases if I paid the rent,' " Clark recalled.

Units haven't been sold to anyone offshore yet, but Clark said he expects about 20 to 25 percent of the project will end up being sold to interested parties in China.

The interest in retirement homes reflects a slowly changing attitude toward elderly care by the Chinese, who along with other Asian ethnic groups, have long viewed the care of elderly parents as the sole responsibility of the children, senior care experts said.

"We have a new generation of people, people who are working women. They're going to college, they're going to universities," Clark said, "and they want to put their credentials to work, and usually it's the first-born daughter or first-born daughter-in-law that's traditionally taking care of mom or dad. They don't want to do that anymore."

Sam Wan is executive director at Kin On Health Care Center in Seattle, a 100-bed facility that he says is always full. The elderly who live at Kin On are mostly Chinese who rely on Medicare and Medicaid - US federal programs that provide health coverage to people 65 and older - who have their monthly assisted care programs available through subsidies. The amount the elderly pay out of pocket can vary from as little as $50 to close to $1,000.

"When we first started, we were the only choice for seniors if they needed help and cannot be by themselves at home," Wan said. "But now there are more housing options, and when people have more options," sending the elderly to nursing homes becomes more acceptable, he said.

The idea of putting elders or loved ones in nursing homes is a "huge barrier, huge hurdle to overcome," said Daphne Kwok, vice-president of engagement with Asian-American and Pacific Islander strategy at AARP. "We know that to be able to take care of our own is what we've grown up to understand, and that's just part of our every day life too."

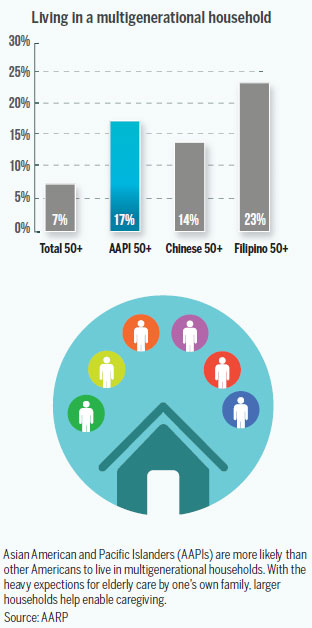

Research shows that the Asian community is almost twice as likely as the general American population to take care of elders. About 70 percent of Asians believe that they should be doing or should have done more for their parents, compared with 48 percent of the general public, according to a nationwide study conducted by AARP on caregiving among Asian American and Pacific Islanders.

"The care of elders among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) carries with it attitudes, beliefs, and practices that can be starkly different from those of the general population," said a report released by AARP in November 2014. Because most older AAPIs are immigrants, they bring with them cultural expectations from their home countries, the report found.

Among the Chinese in particular, there is a "reluctance to discuss end-of-life-related issues" due to superstition; there is a belief that mentioning something bad can make it happen, AARP found, and all the cultural factors may make it hard for younger Asian Americans to meet such expectations.

"There's going to be more and more demand as we continue to age," Kwok said. "One of the things we're trying to do is inform and educate our community that at a certain point, you really need to provide assistance to our loved ones through assisted care or nursing homes," Kwok said. "No matter how much you want to take care of your loved ones, it's just going to be very, very difficult, medically and physically as well."

The Asian-American population contains the second-fastest growing group of people aged 50 and over, and that number will triple in the next 40 years, from 4.3 million to 13.2 million, according to AARP.

Gary Tang, director of the aging and adult services program at the Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS) center in Seattle, said that the changes in attitude come with expectations for the "sandwich generation", those in their 40s and 50s who have both children and parents and in-laws to take care of, feeling pulled on both ends.

This is particularly hard for Asian families, who at more than two times the national average live in multi-generation households and away from major metropolitan hubs in order to live in more spacious homes to accommodate more people, he said.

"If they have kids, they think about the school district, they think about whether to live in a four-bedroom house," he said. "But when a family moves to the suburbs, transportation becomes a big issue for the aging parents who try to go to a bilingual doctor, go to a senior center, library or exercise. Then living in a suburb is not going to work really well for aging parents," he said.

What social services workers need to do is create a more welcoming environment for the elderly and their children so that they are aware of what goes on in retirement homes, Tang said.

Too often elderly Asians have a fear that going to a retirement home is akin to living in jail, and this leads to refusal of nursing services. It can ultimately be harmful for those who need 24-hour medical care or assisted living, he added.

AARP's Kwok echoed Tang's sentiments, saying that Asian communities need to start having more end-of-life conversations so that they are aware of the options available.

"These kinds of conversations and education forums are very much needed in our communities, so that everyone knows what to do, where to go for resources, for information, what the options are for their loved ones, so that they make informed decisions before crisis hits," she said. "We know that once the crisis hits, there are tremendous stressors that get placed on the family and family relationships."

amyhe@chinadailyusa.com

Xi: new chances for Sino-US ties

Xi: new chances for Sino-US ties

Mine clearance mission on China-Vietnam boarder

Mine clearance mission on China-Vietnam boarder

Subway graffiti takes passengers underwater in Foshan

Subway graffiti takes passengers underwater in Foshan

'Always look up': China's skyscrapers from below

'Always look up': China's skyscrapers from below

'Wall of love' in Shenyang paints romance in new color

'Wall of love' in Shenyang paints romance in new color

Top 10 countries that export most foodstuff to China

Top 10 countries that export most foodstuff to China

Diapers and a diamond lead to a marriage proposal

Diapers and a diamond lead to a marriage proposal

Chinese go the distance for marathon

Chinese go the distance for marathon

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

Xi pledges $2 billion to help developing countries

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US to accept more refugees than planned

Li calls on State-owned firms to tap more global markets

Apple's iOS App Store suffers first major attack

Japan enacts new security laws to overturn postwar pacifism

US Weekly

|

|