The shifting sands of change in an ancient land

Updated: 2013-01-21 07:58

By Cui Jia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

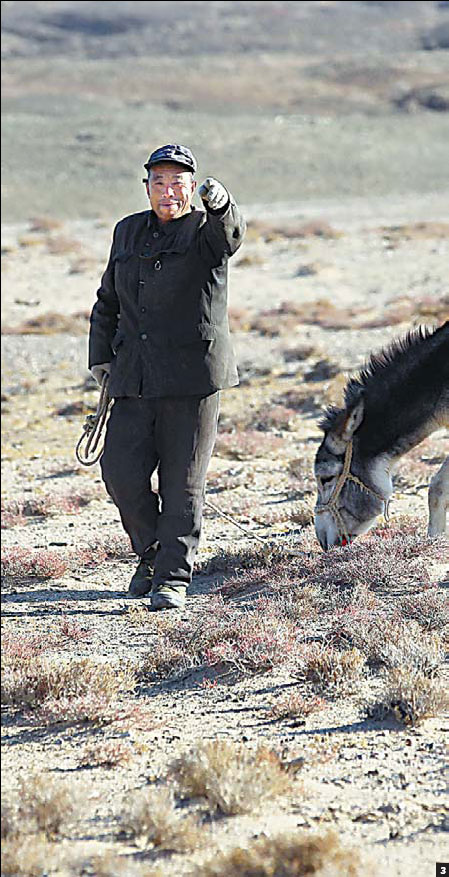

Bariba, 61, a resident of Mazongshan, Gansu province, welcomes visitors to his home with a traditional warm greeting. Zou Hong / China Daily |

More lucrative pastures lure herdsmen from the traditional Gobi lifestyle, reports Cui Jia.

Editor's note: This is the sixth in a regular series of reports brought together under the banner "Lost Horizons", which aim to show life in the less-reported areas of the country and to give a voice to those whose words often go unheard. Slideshows and video footage are also available at www.chinadaily.com.cn/video

After hours of driving through Gansu province, following the modern highway that runs alongside the remains of ancient walls and watchtowers made out of gravel and soil, the surroundings suddenly changed when we took the exit to Mazongshan - one of the least populated towns in China.

Almost without warning, the landscape switched from the yellow silt of the Loess Plateau to the black sands of the Gobi desert.

Mazongshan, which translates into English as "Horse Mane Mountain", occupies a unique spot in the ageless Gobi. Numerous small black hills are scattered across the vast, arid spaces paved with flat, black stones that shine dully in the broiling sun. Long ago, travelers on the only road leading into the town decided that the cascading hills resemble the flowing manes of wild horses, and the name stuck.

Linking the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region with the Inner Mongolia autonomous region and Mongolia, the town was once an important gateway on the Silk Road, the ancient caravan route used by merchants in times long past. Situated in Gansu's far northern corner, Mazongshan covers an area of more than 38,000 square kilometers, making it approximately equal in size to Jiangsu province. However, the population is a mere 1,420, according to recent statistics from the local government.

During the bone-shaking ride along the bumpy road that cuts through the lifeless black desert to the town center, the landscape resembles that of another planet. No maps of the town exist because they are unnecessary. Mazongshan consists of just two streets, a statue of an ibex - a type of wild goat - stands at the intersection. The Gobi is a prime natural habitat for animals such as ibex, wild horses and camels. The profusion of wildlife saw Mazongshan open one of Gansu's three official international hunting grounds in 1988.

"Although our Gobi may appear lifeless to outsiders, we know how to find water and mobile phone signals," said Bariba. Like most of the locals, who have adapted to a lifestyle based on grazing camels and mountain goats, the 61-year-old is a member of the Mongolian ethnic group.

While waiting to be picked up to check on his camels, Bariba enjoyed himself by standing at the ibex statue and watching several young people playing pool outside a grocery store. He greeted passersby with enthusiasm, calling out the names he knows by heart.

Buried treasure

"I wonder what sort of treasures are buried underneath the black Gobi?" mused Bariba, staring at the dusty off-road vehicles a geological exploration team had parked outside the restaurant next door. Scientists have discovered 128 mineral deposits in Mazongshan, including gold, coal and iron.

Hopping onto the pickup truck, Bariba began the search for his herd of 12 camels. The truck soon left the main road and entered the Gobi, being driven through scattered clumps of thick, stunted bushes. Bariba's family moved to Mazongshan from neighboring Inner Mongolia 50 years ago. "I really envy those herdsmen in Inner Mongolia who enjoy rich grasslands, but I'll never leave here," he said.

Without any navigation systems or tracking devices, the "camel boy" directed the driver to the area where his camels usually wander. With years of experience to guide him, Bariba has learned to identify unique stones and use them as landmarks, something an outsider would never be able to do.

The herdsmen don't graze their camels. Unlike the mountain goats owned by the herders, camels need to walk a long distance for food every day in the deserted Gobi. Instead, the herdsmen set up drinking spots for the camels. When they need to collect the camel fur, the herdsmen simply wait for the animals to turn up at the watering holes and catch them.

"They are actually half wild. God knows how much camel spit I've had on my face over the years," said Bariba, laughing. When camels feel threatened, they spit and it can get pretty smelly because camel spit consists of bile from its stomach mixed with saliva, he explained.

"Stop!" shouted Bariba suddenly, causing the driver to hit the brakes. "Let me make a phone call right here. It's the only spot in this area that can receive mobile phone signals," he said.

In Mazongshan, herdsmen from the same village may live four or five hours drive away from each other because it's so big, said Bariba. "Before we had mobile phones, it took me a whole week to travel around on horseback to inform all the villagers about a meeting."

An hour elapsed, but there was no sign of any camels. "It happens sometimes. They might have walked a long way to find fresh grass. I just hope they haven't been attacked by wolves," he said. "We've seen more wolves in recent years than ever before."

Bariba's next stop was the pen that holds his 400 mountain goats. The truck stopped at a brick shelter, which has replaced the old herdsman's traditional Mongolian yurt in the Gobi. Bariba has moved his old yurt into the town center and uses it as a restaurant where he serves traditional Mongolian cuisine to visitors.

"I used to stay here on my own, but I was never lonely because I had my radio to keep me company. It can receive more than 58 stations. So, although I am in the Gobi and a long way from Beijing, I still know about all the major policies," he said.

In 2011, he heard a Mongolian-language news report that the State Council would sponsor a subsidy-and-reward program to help herdsmen prevent and reverse the damage caused to China's grasslands by overgrazing. The next day, he rushed to the town government to collect his share, only to discover that the policy wouldn't be implemented until 2012. He told the government official that he would return to collect his cash when the policy came into force.

As promised, Bariba received his 27,000 yuan ($4,338) subsidy in 2012, but had to sell half his goats to protect the Gobi grassland from overgrazing. "It's something we had to do sooner or later. Mountain goats eat the roots of the grass, and too many of them will destroy the grassland forever."

To scare away wolves at night, Bariba ties empty liquor bottles to the wires surrounding the goat pen in the hope that the sound of the bottles bouncing against each other will spook the predators.

"It used to work, but the wolves are getting smarter and aren't scared of the bottles anymore. Two wolves jumped into the pen one night last year and killed more than 10 goats," he said. More than 3,000 head of livestock, including mountain goats and camels, were killed by wolves in Mazongshan in 2012.

Herdsmen don't have guns to shoot the wolves anymore, because all the firearms have been confiscated by the local authorities, but the fences erected across the Gobi to indicate the prohibited-grazing area have trapped the wolves in the desert, said Bariba. "One of my friends lost more than 100 goats in a single night. We haven't seen this many wolves for a long time. It seems like they reappeared all of a sudden."

Threat from mining

Not everyone shares Bariba's view of the danger posed by predators. "Last year, the local government sent people to shoot the wolves, but they couldn't find any," said Malan Qiqige, resplendent in a traditional Mongolian gown. The 47-year-old's family owns more than 700 goats, 12 camels and 20 horses.

She said the pollution caused by heavy mining in the area is far more damaging than wolf attacks. "The grass dies once it's been covered by the ore that falls from the trucks. Also, the livestock are at risk. They can easily die after consuming toxic waste such as plastic bags."

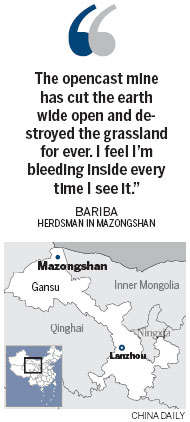

Bariba said there has been a huge increase in mining since 1998 and said that one mine in particular has left an impression on the herdsmen, but not a favorable one. He's referring to the Tulu opencast mine, which began operations in 2003 and has left a scar on the Gobi more than 7 km long.

To expose the seam of coal, the topsoil has been removed layer by layer. It has become a man-made black canyon stretching as far as the eye can see. The air around the mine is filled with the toxic fumes released by the coal as it combusts on exposure to direct sunlight.

"The opencast mine has cut the earth wide open and destroyed the grassland for ever," Bariba said. "I feel I'm bleeding inside every time I see it."

However, he admitted that the mines also bring jobs. Many herdsmen have traded in their livestock for trucks, and have transformed themselves from "camel boys" to well-paid drivers, transporting ore from the desert. Many park their huge trucks next to their houses.

Bayishi Hule had just returned from his pasture, more than 100 km away from the family home in the center of town. Although the 38-year-old herdsman visits the town twice a month, the rest of his time is spent out on the black Gobi, just like the numerous generations that came before him.

His wife has urged him to buy a truck because she heard that their neighbor has made a fortune, but his ambitions go no further than swapping his yurt on the Gobi for a brick shelter. "I will continue being a herdsman, but I don't want my son to do it. I want him to study hard and become a businessman."

Bariba, because of poor health and advancing years, has hired a worker to graze his goats. In the meantime, the herder remains in the comfort of his house, watching the news on satellite TV instead of listening to his beloved radio. However, he doesn't fully trust his understudy and often makes random visits to the pen to inspect his work. "No one can take care of my goats better than I do."

Also, thanks to a wind farm that began operations at the end of 2011, the residents of Mazongshan can finally enjoy the benefits of electricity 24 hours a day. Before the wind farm was established, the town's electricity came from small diesel generators that only provided a few hours of power each day.

Bariba's three daughters and one son have all abandoned the herding life and have found jobs outside the Gobi. "Herding in the Gobi has become increasingly difficult, and many young people have decided to work elsewhere. I fear that there won't be many of us left here in the future," he said, looking at a portrait of Genghis Khan, the founder and Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, that hangs in his house next to a model of Tian'anmen Square in Beijing.

"The herding lifestyle that was passed down by our Mongolian ancestors is facing huge changes. People are leaving the grassland in search of better opportunities - I really don't know if that's a good or bad thing," he admitted.

Contact the reporter at cuijia@chinadaily.com.cn

Jiang Xueqing and Tang Yuecontributed to this story.

|

1. The view overlooking Mazongshan in Gansu province, with small black hills scattered across vast arid areas, resembling a horse's mane. 2. Herdsmen are encouraged to raise fewer mountain goats to protect the Gobi grassland, because goats eat the roots of grass. The herdsmen have received a government subsidy. 3. A herdsman points the way in the Gobi desert. 4. Bayishi Hule's family - his mother and two siblings. 5. Bariba digs a well in the Gobi to water his mountain goats. 6. An opencast mine in Mazongshan. Heavy mining has threatened the environment of the Gobi. 7. To scare away wolves at night, Bariba ties empty liquor bottles to wires surrounding the goat pen in the hope the sound of bottles bouncing against each other will deter the predators. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

(China Daily 01/21/2013 page6)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|