A lost people

Updated: 2013-01-24 06:02

By Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Western Xia Tombs, acclaimed as "Oriental Pyramids", are the prime attraction in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui autonomous region. Liu Xuezhong / For China Daily |

Genghis Khan obliterated most of the Dangxiang ethnicity for refusing to join his invasion of the Khwarezmian Empire. Now archaeologists are trying to dig deeper to find out more about the race. Erik Nilsson joins the search.

Archaeologists are digging for - and unearthing - answers about the Dangxiang ethnicity, whose saga was buried with them when they virtually vanished in a mass slaughter.

They're mining the Western Xia (1038-1227) Tombs for narrative nuggets to resurrect the stories of the people who perished in Genghis Khan's final battle.

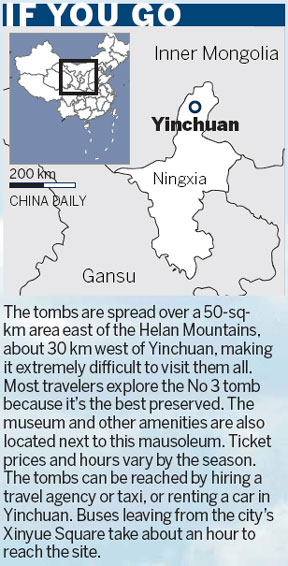

Little is known about the Dang-xiang, also called the Tangut. Most of what has been determined has been gleaned from the Western Xia's nine imperial mausoleums and 250 royal family tombs that stud the desert outside of Yin-chuan, capital of today's Ningxia Hui autonomous region.

Genghis Khan essentially obli-terated the Dangxiang for refusing to join his invasion of the Khwarezmian Empire.

So these tombs' ruins commemorate not only the ethnicity's rulers but also their tribes' last stand.

But only one of these structures - the No 3 mausoleum, believed to belong to the Western Xia's first emperor - has been fully excavated.

Like Dangxiang history, the tombs remain relatively obscure in public consciousness.

They're skeletons of their previous physiques, stripped by decay of the tiled flesh that made them the first fusion of traditional ethnic Han mausoleum design and Tibetan Buddhist temple architecture.

The tombs may have served as a metaphor for the ethnic group's exterminated tribes. Most of the sepulchers' structures have worn away, like the saga of the people their inhabitants ruled.

The sands of time have ground the structures from octagonal towers into conical earthen mounds - nubs of their former selves. They look like huge loess dollops, or colossal termite mounds, although their initial splendor is believed to have rivaled that of Beijing's iconic Ming Tombs.

But the burial chambers' current shapes have endowed them with marketing magnetism. The "Oriental Pyramids" are by far the city's principal attraction.

Their contours resemble the Helan Mountains that serve as their backdrop. Helan's peaks are crowned by the Great Wall's terminus, constructed to keep out the Mongolian invaders, who ultimately breached the bulwark to extinguish the Western Xia.

But while most tribes were wiped out, some Dangxiang outlasted their empire. One excavator is believed to be the last emperor's 23rd-generation descendant.

The main tombs were discovered during the construction of a military air base in 1972. The unearthing of ancient bricks and pottery offered the first hints that the soil encrusted something special.

That led the military to bring in archaeologists, who discovered coins, sculptures and tablets engraved with the Western Xia's unique characters.

This enticed them to dig deeper, whereupon they exposed the mausoleums.

Only nine of the empire's 12 kings' final resting places have been found.

But many smaller mounds belonging to imperial relatives or left empty - presumably as red herrings to sidetrack tomb raiders - occupy surrounding farmlands.

However, most tombs are rarely visited, as they are dispersed, difficult to reach and in ruin. Many believe they might be constellated as such to emulate prominent heavenly bodies' positioning.

While the rulers' tombs are crumbling, the four corner towers, sacrificial halls and mourning platforms surrounding each of them have eroded almost beyond recognition.

Yet, even in its original splendor, the 50-sq-km burial complex would offer deficient testimony of the dynasty that ruled about 830,000 sq km of today's Ningxia, Gansu province, much of the Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous regions, some of outer Mongolia, and northern Shaanxi and eastern Qinghai provinces.

The Western Xia dominated this sphere by counterbalancing expansionist hostility against land-lusting neighbors - the Song (960-1279), Jin (1115-1234) and Liao (916-1125) dynasties.

The dynasty was founded when Li Yuanhao's father, Li Deming, crushed the Huang Chao peasant insurgence on behalf of the declining Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

Li Yuanhao prolonged power by resisting Song subjugation after the Tang expired. But the last emperor was unable to fend off Genghis Khan's unified Mongolia, which launched six campaigns against the Western Xia in the two decades preceding the empire's fall.

The conquest took the lives of not only the Western Xia's last ruler but also tens of thousands of civilians. Many tribes were totally exterminated.

Some of the remaining Dang-xiang joined the Mongolian military. Others diffused around the continent. Artifacts bearing Dangxiang script from as late as the 16th century have been discovered in Central China.

The Western Xia Museum in the tomb complex houses more than 670 artifacts and more than 450 research papers on the empire.

These trace the ethnic group's anthropological evolution through its power spike, starting with its abandonment of nomadic life, and early adoption of Tang songs and legal systems. It later absorbed elements of the Liao and Song dynasties, and the Tibetan and Uygur ethnicities.

But some indigenous traditions persisted. Men shaved their heads, aside from pigtails on the sides and one ponytail rising from the crown in deliberate contrast to the Han.

The defiant were beheaded. The decree was: "Lose your hair and keep your head, or lose your head and keep your hair."

It's unsurprising given the expansionist ambitions of the Western Xia and its neighbors that many of the museum's relics are of military origin. The empire was born, lived and died by the sword.

Among the expectable arrowheads, spears and helmets are a studded porcelain grenade and one of only two sets of chain mail from the period.

Next to the museum is a courtyard filled with scaled-down replicas of the original mausoleums. The side halls display wax-statue recreations of tales from the empire's rise to its demise.

Though inanimate - even cheesy - these mannequin scenes breathe some life into the story of an empire that disappeared along with most of its people - one that's only now resurfacing as archaeologists sift through the sands of its time.

Contact the writer at erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

A downsized replica of the original mausoleums, believed once to be as splendid as Beijing's iconic Ming Tombs. Hu Tong / For China Daily |

|

The 670 artifacts on display at the Western Xia Museum trace the ethnic group's anthropological evolution through its power spike. Zhang Bo / For China Daily |

(China Daily 01/24/2013 page19)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|