Inspiration from a group once shunned

Updated: 2013-01-30 07:24

By Yang Wanli (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Leprosy patients Hu Shu, 85, (left) and Huang Xilao, 81, enjoy a light moment while undergoing treatment in a hospital in Guangdong province. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Leprosy patients show the spirit of life, reports Yang Wanli in Dongguan, Guangdong province

Approximately 26 kilometers off the coast of Taishan city in Guangdong province lies a small island called Daqin. Although famous for its natural beauty, the island is not a summer resort, nor a haven of peace and happiness complete with fishermen and folk songs.

Hidden from the eyes of the world, the island was once regarded as a hellish place by local people who said it was populated by "monsters" lacking fingers, toes and sometimes even entire limbs. Children were scared into good behavior by tales of ugly, distorted faces.

But the inhabitants of Daqin were not monsters: They were Mafeng Lao - a local name for those with leprosy.

For almost a century, Daqin was the largest of Guangdong's 100-plus leper colonies. Established in 1924 to isolate the sick from other residents, the island was home to almost 2,000 patients at its peak. By 2011, when the facility was closed, the number of residents had dwindled to 44 with an average age of 75. Some were blind and bedridden. Others had seen their bodies ravaged by the consequences of disease.

Wu Yunqi is one of the Mafeng Lao. He lived on Daqin for nearly 60 years. Although his first symptoms appeared at 13, Wu's condition wasn't fully diagnosed until 18 years later. He was quickly sent to the island and never saw his family again.

The island had no running water, no electricity, no TV and sometimes, during the typhoon season, no food other than salted vegetables.

Until 1998, when the local government donated a speed boat to the community, the residents' only connection with the outside world was a small wooden sailboat that visited once or twice a week. Life was counted out by the day.

For the past half century, 90-year-old Wu has prayed every day for spiritual support to help him cope with a condition that results in atrophy of the nerve endings. The loss of sensitivity leaves patients vulnerable to cuts and grazes that go unnoticed. The lacerations then become infected. Wu's left leg is crippled and bears many terrible scars. He has one enduring hope - that he will see his two children again.

In 2011, the island's last patients were transferred to Si'an island, close to Dongguan city, famous for its manufacturing base. The move was a government project to improve living conditions for the sufferers. Si'an island, a mere five-minute boat ride to the shore, is far more accessible than Daqin, which took at least an hour to reach.

Wu believed that moving closer to the shore has improved his chances of seeing his family again. However, the reality is that his life will end without reconciliation.

Late last year, Wu's story was taken up by the local media and eventually his son and daughter, both in their 60s, came forward. However, they refused to visit the island and see their father. The only image Wu has of his children is a photograph of them with their grandmother. The children will have changed, though, as his son sent it in the 1970s.

"I have never stopped missing them, not through all the decades we've been apart. I can't have too many days left to me, but" Unable to continue, he stopped talking and simply stared into the distance. It was some time before he spoke again. "I won't mention my hopes of seeing them again," he said, sounding resigned.

Wu isn't the only Si'an resident with family he never sees. The local hospital threw a party for families on Jan 12, but only about 20 of the 80 residents were visited by relatives. The rest either lost contact with their families long ago, or the families simply don't want to meet them.

Fear and discrimination

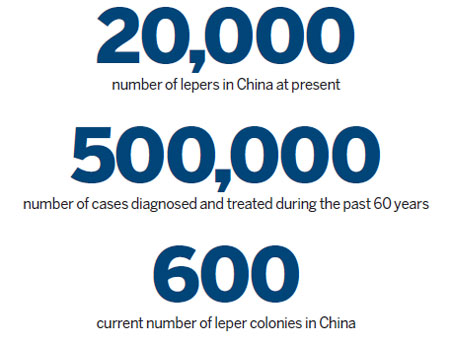

Leprosy was once one of the most serious infectious diseases in China. However, in the past 60 years, about 500,000 cases have been diagnosed and treated. As in other countries with a high incidence of the disease, patients are kept in isolation and treated with antibiotics and other drugs. These, and other measures, have seen the incidence of new cases decline sharply.

Only about 3 percent of Si'an's residents still suffer from leprosy. The rest have been successfully treated but there are lingering effects, such as skin ulcers. Poor treatment in the early 1950s reduced nerve sensitivity, resulting in patients damaging and ultimately losing fingers, toes, noses or even limbs in some severe cases.

Some patients were unable to return home because their scars scared healthy people, including family members. Fear and prejudice meant isolation for some, while others were simply abandoned. Most of the patients have had no contact with their families for decades.

A few have visited their hometowns in Guangdong, but didn't visit the relatives who had never visited them.

Liu Zhuquan suffered severe skin ulcers when he was 15, brought on by leprosy. Although the condition was severe, doctors decided not to perform an amputation. The 68-year-old Buddhist said God had been merciful in allowing him to keep his legs.

He hasn't seen his family for a long time, but is just happy to have regular phone contact with his two younger brothers and a sister. "I dare not ask for more, such as regular meetings. My mother died in 1984, but I didn't attend the funeral or my brothers' wedding ceremonies. I don't want my family members to suffer discrimination or to put them under any pressure," he said.

A harsh existence

In the late 1970s, four nuns from Macao arrived at Daqin island with equipment that allowed water to be heated efficiently and quickly. Before that, the patients either bathed in cold water or they heated water by burning wood. Without electricity, lighting was provided by oil lamps donated by churches in Macao, but were only lit from 6 pm to 10 pm each day. There were no beds, so patients slept on wooden boards.

The harsh conditions and hard life on Daqin island made things tough for the residents. Lacking food, patients had to go fishing everyday. Cutting wood inevitably led to cuts and grazes, which often became infected. The wounds healed slowly or simply failed to heal at all, meaning some patients had to have arms and legs amputated.

Many residents turned to religion for support and approximately half converted to Catholicism.

Early in 2007, the central government pledged to improve conditions for the country's 20,000 lepers, and they were moved to 100 dedicated areas that offer improved facilities and medical treatment.

As the poorest colony, Daqin was high on the project list, leading to the 2011 relocation to Si'an. It was the first time that 70-year-old Situ Zhenhuan had seen vehicles and highways. Having been separated from mainstream society for almost half a century, his memories of public transport revolved around bicycles.

Around a month ago, an electric-battery car was donated to Si'an Hospital. Xu Bin, an officer at the hospital, said many of the residents drive the car around the island several times a day. "They are very excited by this unusual vehicle," he said.

However, for most residents, the greatest wish is simply the love and care of their families, said Xu. "But it's hard. Even today, there is still discrimination toward lepers," he said.

Unshakable prejudice

Lu Yineng, 37, was born into a family with close connections with leprosy. He followed his father's career path and became a "barefoot" doctor. Lu described his parents as "supported by a strong spiritual belief".

Lu's father, who was born in a village in Taishan city in 1935, spent years learning basic medicine from a local "barefoot" practitioner. In 1956, he was sent to work with the lepers on Daqin and spent the following 41 years on the island. In 1998, Lu took over his father's job, working as the island's only "doctor" until 2011. "Nobody wanted to work there because of fear and social prejudice. Even a cleaner in the hospital was looked down on by healthy people," said Lu.

He said at least half of the staff at the hospital in Si'an have married colleagues. Most parents are unwilling to allow their child to marry someone whose family has a history of contact with leprosy.

Lu's words were borne out in our interview at Si'an hospital. Some of the doctors and nurses refused to have their photos taken or to be named, to spare their family members from any possible negative reaction.

"Only my wife and daughter know that I treat lepers. None of my other relatives or friends know about my job," said a doctor surnamed Lin, who admitted that most of his colleagues kept their jobs secret. "We prefer to be called 'dermatologists'," he said.

Lin spoke of a colleague whose daughter's engagement was broken off when the family of the prospective groom discovered that her father treated lepers. Even some physicians avoid contact with the sufferers. When the Daqin residents were relocated in 2011, doctors at the general hospital that arranged the move threw away the stretchers used to transport them.

Statistics from Guangdong's Department of Health show that 2,200 patients in the province have been treated successfully, although 2,000 of them have been permanently disabled or disfigured by the disease.

However, around 100 new cases are discovered every year, but improvements in medical techniques mean that most can be treated successfully at general hospitals, and few patients suffer long-term effects.

Public prejudice means that few lepers choose to leave the colony and return home, according to Liu Zhuquan, who was once the leader of the Daqin colony. "They did not want to put pressure on their families. At least in the colony, lepers can live without shame and don't feel the need to hide their deformed bodies," he said.

Despite the despair, many patients harbor artistic designs. Some practise local opera every morning, while others learn Chinese calligraphy or organize troupes to perform traditional Guangdong dragon and lion dances.

Religious support

In addition to the missionaries who have been visiting island colonies in southeast China since the 1940s, other religious groups from overseas, plus volunteers and charity groups, have also provided assistance and care to lepers in colonies around the country.

Li Yida, 43, a Singaporean Chinese, has devoted her time to caring for lepers since early 2010. During the past two years, she has traveled to many leper colonies in the provinces of Yunnan, Jiangxi and Guangdong and met many people from religious groups.

In 2003, Li married for the second time. Her husband is a Singaporean Christian, and a year after the marriage Li, who grew up in Hebei province, also converted to Christianity. "The Bible says we should help those who live in poor conditions and struggle to survive. Taking care of lepers is challenging work that many people refuse to do," she said.

American Leprosy Missions run projects in Guizhou province, and a South Korean organization also funds several colonies.

However, donations have started to dry up during recent decades because the number of lepers in China has declined sharply in the past 50 years. That has led to attention shifting to other developing countries, especially in Africa, where the problem is still acute.

Tang Yue, Jiang Xueqin and Zhang Yuchen contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at yangwanli@chinadaily.com.cn

|

1. Li Zhidi, 90, reflected in a mirror at the ward in Si'an, Guangdong province. 2. The entrance of Si'an hospital. 3. Li Yida (right) helps a patient at the hospital. 4. Yu Bin, 81, sitting in his ward. 5. Hu Shu, 86, enjoys a traditional Guangdong dance. 6. Li Zhidi has lost most of her fingers. Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

(China Daily 01/30/2013 page6)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|