Bones that piece together our past

Updated: 2013-01-31 07:43

By Cheng Yingqi (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The origins of humans have intrigued anthropologists for the longest time. Now an international group of paleoanthropologists has found that humans who lived some 40,000 years ago near Beijing were likely related to many present-day Asians and Native Americans. They reveal the details to Cheng Yingqi.

|

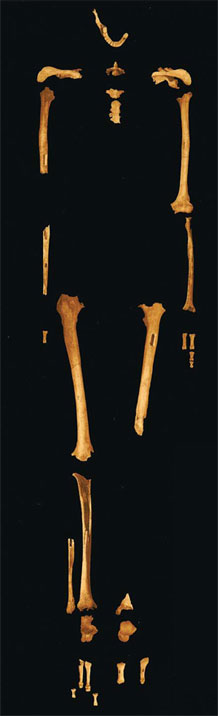

The Tianyuan skeleton was unearthed near the Zhoukoudian site, about 50 km southwest of Beijing. Photos provided to China Daily |

Twelve years ago on a summer afternoon, local farmer Tian Xiumei climbed up a mountain in Fangshan district, 50 km southwest of downtown Beijing, in search of water to irrigate her trees. Halfway up the mountain, she found a small cave, which looked like the mouth of a spring. Tian took a flashlight and dove into the small entrance that only allowed one person to pass through. She was disappointed that there were no traces of a spring inside.

What she found instead were fragments of animal bones, which eventually led to the discovery of a partial human skeleton. Those were actually the bones of modern Chinese ancestors.

Tian's discovery later led to a deeper excavation by scientists from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2003.

On Jan 21 of this year, the scientists released their latest research findings on the bones excavated from Tianyuan Cave. The ancient DNA has revealed that humans who lived some 40,000 years ago in the area near Beijing were likely related to many present-day Asians and Native Americans.

The scientists sequenced nuclear and mitochondrial DNA that had been extracted from the leg of the Tianyuan Cave person, who lived in the region about 40,000 years ago.

Previous DNA evidence on modern man in East Asia could only be traced back to less than 10,000 years ago.

"This individual lived during an important evolutionary transition when early modern humans, who shared certain features with earlier forms such as Neanderthals, were replacing Neanderthals and Denisovans, who later became extinct," says Svante Paabo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Paabo is the leader of the study, jointly conducted by the Max Planck Institute and IVPP.

Gao Xing, deputy director of the IVPP, who also participated in the research, says: "This is the first time that Chinese paleoanthropologists extracted DNA from ancient humans who lived more than 10,000 years ago."

Previously, scientists examined human fossil morphologies and cultural remains on a site to conjecture about the life of the ancient humans living there.

"Traditionally, we infer by observing the fossils and tools on the site, but molecular biology has opened a new door for us," Gao explains.

"For example, based on isotope analysis of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, we found that the Tianyuan Cave man ate freshwater fish, which we had no way to find out from studying fossil morphology, and there is no tool left in the cave for such analysis."

But buried in the cave for tens of thousands of years, most DNA contained in the bone had been destroyed. Bacterial contamination has made it even more difficult to extract the DNA.

"Only 0.3 to 0.4 percent of the DNA belonged to humans. The rest was bacteria," says Fu Qiaomei, primary author of the research paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

"Finding the human DNA is like looking for a needle in a haystack. It needs strong technical support," Fu says.

The Max Planck Institute, as the industry leader in this field, provided technical support for the research.

As early as 2009, the Max Planck Institute and Chinese Academy of Sciences jointly built a laboratory to study the evolution of humanity.

"China has abundant research materials for paleoanthropologists, and that's a major reason that foreign institutes are attracted to China," says IVPP deputy director Gao Xing.

He says that now paleoanthropologists are quite certain about the human evolutionary pathway in Africa and Europe, but there is still a research gap in East Asia.

"East Asia and Africa are the two most promising regions for paleoanthropology research, and the jigsaw will not be completed without figuring out the situation in China," he adds.

As for the theories of the origins of modern human beings, there are two popular explanations: one is that modern humans are descendants of regional archaic-type human groups in Africa and Eurasia about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago; the other is that modern humans thrived about 200,000 years ago in Africa and later migrated elsewhere.

Gao says the latest breakthrough shows that 40,000 years ago, Asians and Native Americans were still related by blood, but their DNA had divided since the time of modern Europeans. Those discoveries are still not enough to give a full picture of human evolution.

"We won't be able to find the answer on our own. Only by gathering the information across the globe will you be able to piece the puzzle of human evolution together," Gao says.

Contact the writer at chengyingqi@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences excavated Tianyuan Cave man in 2003. Photos provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 01/31/2013 page18)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|