Medical care comes to religious groups

Updated: 2013-02-05 07:45

By An Baijie in Dengfeng, Henan province and Shan Juan in Beijing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

A doctor at a hospital in Shenmu county, Shaanxi province, performs a checkup on an elderly woman with pleural effusion, an accumulation of excess fluid surrounding the lungs. Health insurance covered more than 99 percent of the inpatient's medical fees. In 2009, the remote county launched a program which reimburses about 90 percent of inpatient expenses for its residents. Tao Ming / Xinhua |

|

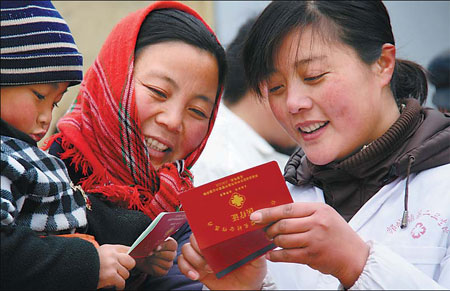

A staff member (right) at a village clinic in Shandong province explains the rural cooperative medical program to a resident. The program now covers 900 million people across the country. Zhang Chunlei / for China Daily |

Universal policy funded by government subsidies extends coverage to communities including monks, nuns, report An Baijie in Dengfeng, Henan province and Shan Juan in Beijing.

Shi Yanlin was taken aback five years ago when some monks asked him how to get coverage under the country's health insurance policies.

Shi, 52, executive director of Shaolin Temple, China's most famous Buddhist monastery, with a history of more than 1,500 years, is in charge of the temple's health and medical issues.

Since 2003, when the country began establishing universal healthcare, religious groups, including Shaolin monks, began to get coverage.

So far, more than 1.3 billion people on the Chinese mainland have joined one of the three basic medical insurance policies that cover either urban or rural residents.

Government subsidies, not mandates, led to that high coverage, said Gordon Liu, a professor of economics at Guanghua School of Management of Peking University.

In the case of Shaolin, to find out how to buy health insurance for the temple's monks, Shi submitted a proposal to the local government during the annual session of the Henan provincial political advisory body in 2008.

He said health insurance should cover the monks even though there were no regulations on religious groups' health insurance at that time.

Jing Shuzhen, director of Dengfeng city's health bureau, said that the government started to plan for the monks' health insurance after receiving Shi's proposals.

"There are many Buddhist and Taoist temples in Dengfeng in Henan, and their demand for medical health must be met by the government," she said.

According to Shi, Shaolin Temple's executive director, the temple spent less than 30,000 yuan ($4,800) buying the government-held public health insurance for its staff members last year, but they finally got a reimbursement of more than 90,000 yuan in hospital costs.

Residency confusion

However, participating in the policy was not easy and confusing at first, Shi recalled.

The primary problem originated from the country's existing policies. For example, a person's health insurance is attached to their hukou (household registration) status. There are two kinds of hukou status, rural and urban, and health insurance for rural residents costs less than it does for urban dwellers.

However, most of the temple's 267 monks were not sure whether their hukou was rural or urban, Shi said.

The current law rules that people with rural hukou have the use rights of farmland, but all of the monks with rural hukou gave up their farmland. As a result, identifying their hukou statuses was difficult.

"Buddhist doctrine says all human beings are equal, and we have no idea about the hukou differences, particularly here within the temple," Shi said.

Because Shaolin Temple is in the rural area of Henan province, the local government enrolled the monks there into the rural health insurance system rather than the urban system in late 2008, said Jing of the Dengfeng health bureau.

"There were no such regulations on religious people's health insurance until 2011, so we kept low profile on this issue at that time," she said.

China launched the new rural cooperative medical care system in 2003 in a bid to ensure that the country's vast number of rural residents have access to affordable medical treatment and to reduce disease-triggered poverty. Under the policy, both the government and individual contribute.

The annual government subsidy for each participant has increased from 20 yuan in the starting year, 2003, to 280 yuan in 2013, statistics from the Ministry of Health showed.

Matching that, individuals under the policy each paid 10 yuan in 2003 and 60 yuan this year.

In return, participants have 75 percent of their inpatient expenses reimbursed under the rural cooperative medical program, and coverage for outpatient costs are further boosted, Health Minister Chen Zhu said at the national health work conference held early last month.

In Henan, rural participants can have at most 90 percent of their medical expenses reimbursed, Jing said.

At Shaolin Temple, in 2012, a total of 415 people, including monks and more than 130 children in the temple's orphanage, participated in the policy, according to the local health bureau.

One of the temple's monks was diagnosed with cancer and died last year. He had about 60 percent of his medical cost reimbursed under the insurance, and the temple paid the rest, Shi said.

"A 78-year-old monk named Shi Xingzhou in Shaolin Temple suffered from heart disease and went to the hospital at least twice a year for surgeries," he said. "An average of 10,000 yuan of his medical expenses was covered by the health insurance every year."

Preventive care

"Even in developed economies like the United States, health insurance is a heavy financial burden for the government," Shi said. "So we encourage the temple's people to protect themselves from getting sick by doing physical exercises as often as possible."

Most of the monks in Shaolin Temple are younger than 40 years old, so their medical expenses are not large, Shi noted.

Also, Shaolin Temple has a public-funded medicine bureau, where the monks and the tourists can get medicinal herbs free of charge to treat some minor diseases.

To date, the number of people covered by the new rural cooperative medical care system has surged from 80 million in 2003 to 900 million nationwide now.

"The coverage has kept growing though it's not so generous," said Wu Ming, assistant director of the Peking University's Health Science Center.

Also, as an important part of the ongoing medical reform in China, the system helped the country edge much closer to universal healthcare, she said.

By the end of 2015, basic health insurance coverage is expected to rise to about 98 percent from the current 95 percent, according to the Ministry of Health.

This is despite the fact that the coverage is not mandatory, said Liu, the economics professor.

Wang Yuliang, a resident of Sanyao village in Xi'an, Shaanxi province, said he joined the policy in 2004.

"I only paid 10 yuan as the annual premium and got a reimbursement of more than 2,000 yuan that year," he said, adding that the policy is not as good for outpatient care as it is for inpatient services.

"But given the quite low premium, I will constantly participate," said the 54-year-old man, who has diabetes and high blood pressure.

Some, however, thought otherwise about the policy.

Jing, the health bureau official, said that the monks and nuns at Sanhuangzhai Buddhist Hall turned her down when she asked if they would like to buy the health insurance.

"A 92-year-old nun told me that she has gotten used to the traditional herbal therapy self-provided at the Buddhist hall, and she doesn't want to go to a hospital," Jing said.

Besides, the Buddhist hall is on top of a 900-meter mountain, and it's difficult for the elderly nuns and monks to go down to get to the hospital, she added.

Shi, the Shaolin Temple executive director, suggested that the government should attach more importance to public education of basic health.

"If 30 percent of the government's medical cost could be used to educate the people about how to prevent diseases, there will be fewer patients, and the government's health insurance burden will be eased," he said.

Famous for its kung fu performance, Shaolin Temple has a higher income from ticket sales than many other temples, and it can afford to pay the monks' medical expenses.

"For many less famous temples, where there are not as many tourists, health insurance might help more to ease the monks' financial burden," Shi said.

Nationwide, local governments issued rules in recent years concerning health insurance coverage of religious groups.

In general, they can choose to participate in the policies according to the location of their religious institutions like temples, Jing said.

Wu added, "No one should be left out if they were willing to join."

Contact the writers at anbaijie@chinadaily.com.cn and shanjuan@chinadaily.com.cn

Xiang Mingchao in Zhengzhou contributed to this story.

(China Daily 02/05/2013 page7)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|