Helping with heart

Updated: 2013-02-19 07:54

By Liu Xiangrui (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

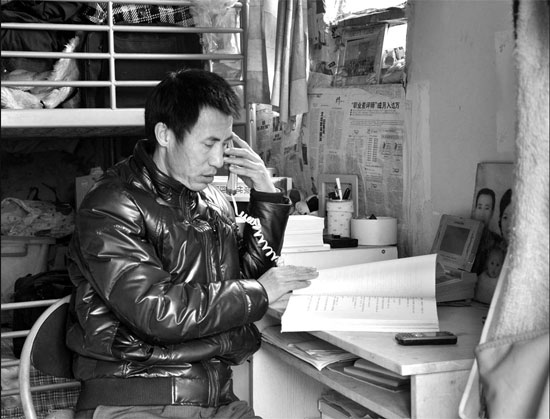

Chen Jun sits by his desk and answers phone calls from migrant workers who often pour out their woes while chatting with him. Photos by Liu Xiangrui / China Daily |

He's a simple man, but he has managed to lend a listening ear to those who are less fortunate. Liu Xiangrui finds out how a farmer in suburban Beijing has been reaching out to migrant workers in the capital.

For the last 10 years, it has been part of Chen Jun's daily routine to sit by his desk and wait for phone calls from total strangers. His home is a dilapidated three-room bungalow in suburban Beijing.

In a room that is just under 6 square meters, he has crammed a bunk bed piled high with hoarded possessions, a bookshelf he made himself that is stuffed with rows of psychology books and a desk with a telephone and thick copies of call records.

This is the 43-year-old farmer's bedroom and office.

Chen dropped out of school at 19, and left his rural home in Zhangjiakou, Hebei province, with his parents in 1997. He began growing vegetables on a rented piece of land on the outskirts of Beijing and ekes out a meager living.

While most vegetable farmers are more concerned with making a living, Chen has surprised many by starting a helpline for migrant workers in 2003.

Before that, he was actively volunteering with an NGO that offered free legal consultation, training, books, and so on for migrant workers. His honesty had won trust from many of these migrant workers, who often poured out their woes while chatting with him.

When a young man had complained about his boss deducting his wages without good reason, Chen comforted him as much as he could. The grateful worker thanked him repeatedly for just listening.

"His words reminded me of my own life as a migrant worker," Chen explains, and says he realized that the emotional needs of these migrant workers are often neglected.

"We work in a new city away from our family, and can't even find someone to talk to when we are distressed," Chen adds.

Chen spent 200 yuan ($34) and installed a telephone at home, and called it the "hotline for worries".

"I know I can't do much, but at least I am willing to listen to their troubles and worries. Sometimes it makes people feel better simply to talk it out."

Chen cycled around the area where he lived and handed out hand-written flyers to the thousands of migrant workers also living there. The flyer explained the helpline idea and also gave the telephone number.

"It was a long wait for the first call," Chen remembers. The first few callers were reluctant to talk and some even hung up without speaking a word. To make the callers more relaxed, he promised total confidentiality, and even assured them they could sue him if he broke their trust.

Also, he had to contend with mockery about his intentions, and his qualifications, and he admits that this put him under great pressure.

"Some keep reminding me that I am just a farmer, while others asked: 'Do you understand psychology at all?'" Chen recalls.

Chen admits it was hard during the early months, and he had thought about giving up.

"While others could confide their doubts in me, I had no one to turn to. Gradually, their burdens became mine." As a result, he himself became depressed for a time and was easily agitated by the little things in life.

The media picked up Chen's story in 2004 and he received professional advice from some psychologists, who helped him both with his own problems and his consulting skills.

According to Chen, the helpline calls surged after that.

Many even called from other cities, and so that he would not miss any calls, he opened two extensions, one with a recording function.

Since Chen has to work his farm during the day, he says he can only manage the helpline at night, and he often stays up late. But he enjoys what he is doing and would carefully take notes of every call.

His hard work paid off, and he successfully talked a girl out of committing suicide in 2006.

"I might not have been able to do that without some knowledge of psychology," he says.

In the six years since it started, Chen's helpline has served more than 11,000 people.

Li Xue, 27, a native from Hebei province, is grateful that Chen pulled her out of her days of despair six years ago. A garment factory worker then, Li was having trouble with her boyfriend and an equally hard time with her dormitory room mates and her colleagues.

When she learned about Chen's helpline on radio, she called him and was immediately impressed by his patience and affability.

"In the end, even I got bored with my stupid questions but he still comforted me patiently," she says. Li is now a good friend and still calls him often for help.

Chen also does his best to help migrant workers in other ways.

In 2006, he started a children's center at his already crowded home, after he realized that many worker neighbors' children had no place to stay while they worked. Thanks to volunteers and donations, the center has helped nearly 1,000 children and more than 1,500 migrant worker families with preschool education.

His charitable efforts won him respect from many, including his wife, who gave up her job as a high school teacher in her hometown and married him in 2007.

"He is brave enough to do what he wants," his wife Li Xiaofeng says, and so she supports him in all he does.

Their rented land was taken back in 2009 for a construction project, and Chen's family had to stop growing vegetables. The family, the last household left on the land, will have to move away soon.

The number of calls on the hotline has dropped now as media coverage cooled in recent years, but Chen insists he will continue the service wherever he moves. Life is worth living as long as he can help someone, he says.

As a sum of all the years manning the helpline, Chen has written a book, based on all he has observed. The most common problems among migrant workers, he says, are all about marriage, salaries, human relations, future development and the education of their children.

The first draft of the book, with about 200,000 words, is ready. "I want to publish it in the future so society can understand more about the conditions of the migrant workers' lives and care more about their problems," he says.

Contact the writer at liuxiangrui@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Chen Jun also runs a childcare center at his already crowded home to help neighbors who have to work and have no time to look after their young. |

(China Daily 02/19/2013 page20)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|