Taking a lead in fight against malaria

Updated: 2013-02-20 07:15

By Shan Juan in Beijing and Li Lianxing in Nairobi, Kenya (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Top: A patient receives medical treatment from a Chinese doctor in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. Chinese doctors often provide free services to local people. xinhua Above: A child (front) with malaria waits for treatment at a refugee camp in Abidjan, a port city in Cote d'Ivoire. One million people are killed by the disease in Africa every year. Ding Haitao / Xinhua |

Smear campaign against Chinese drug companies 'driven by market forces', report Shan Juan in Beijing and Li Lianxing in Nairobi, Kenya.

Despite a number of reports suggesting that legitimate Chinese pharmaceutical companies have been exporting counterfeit anti-malaria medicines to Africa, the country continues to provide aid in the fight against the mosquito-borne disease.

Malaria causes approximately 1 million deaths in Africa annually, many victims being children under the age of 5.

In January, China donated malaria treatments worth $720,000 to Chad, where the illness remains one of the major causes of death.

Chinese-made anti-malaria drugs containing artemisinin, which is derived from wormwood, are cheaper, more effective, and provoke fewer adverse reactions than other treatments, which usually have quinine as the main active ingredient, according to Huang Jianyin, deputy secretary-general of the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies.

Chinese anti-malarials are mainly exported to Africa through government assistance, international organization procurement and the continent's existing sales networks.

On Jan 16, a report in The Guardian newspaper in the UK claimed that large parts of Africa are under threat because of the distribution of fake and poor quality anti-malarial medicines made in China.

Michael O'Leary, the World Health Organization's representative in China, said the reports often fail to provide sufficient verifiable details on the country of origin of the counterfeit products.

"And sometimes, these counterfeits actually pass through several countries before the final packaging and sale in the target countries," he added.

Because the origins of the drugs are deliberately obscured by the producers, it is extremely difficult to trace the manufacturing and distribution channels, which are often coordinated by well-organized criminal syndicates, he explained.

But O'Leary admitted that fake anti-malarials and other counterfeit medicines have been detected in Africa over a long period and pose a threat to public health.

The question is: Where do the fakes originate and who is making them?

Cao Gang, vice-dean of the China Chamber of Commerce of Medicines & Health Products Importers & Exporters, said Chinese-made malaria treatments are popular in Africa because of their affordability and efficacy and are therefore likely to be targeted by counterfeiters.

Meanwhile, Yin Li, director of China's State Food and Drug Administration, suggested that market dynamics may be one motive behind the allegations.

Given increased competition in the pharmaceutical industry, and the rising global potential for drug production and supply, "the drug issue has become subtly subject to existing trade protectionism and the current economic recession," he told the administration's annual work meeting on Jan 10.

A report in People's Daily in late 2012 suggested that the accusations may be related to China's increasing share of the African pharmaceutical market.

Cheap, but effective

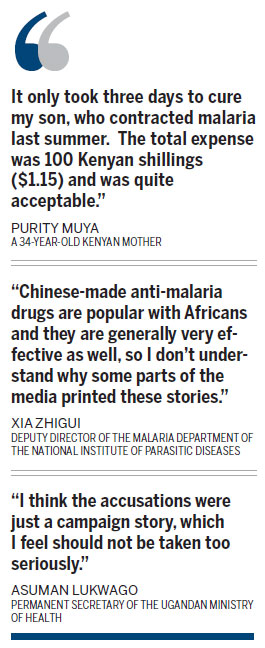

Purity Muya, a 34-year-old Kenyan, said her son was saved by Chinese anti-malaria medicines.

"It only took three days to cure my son, who contracted malaria last summer," she said. "The total expense was 100 Kenyan shillings ($1.15) and was quite acceptable."

Fayyaz Mohammedtaqi, chief of pharmacy and outpatient services at the Aga Khan Hospital in the Tanzanian capital, Dar es Salaam, told Xinhua News Agency the hospital uses two types of Chinese-made malaria treatments, Duo-Cotecxin and Artesun.

"They are as effective as those made by Western companies, such as Coartem by Novartis, which, however, is far more expensive," he said.

Stephen Kyebambe, a physician at China-Naguru Friendship Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, said an increasing number of patients in Africa choose cheap, but effective, Chinese drugs in preference to Western-made medicines.

Meanwhile, a number of industry experts dismissed the media reports.

Xia Zhigui, deputy director of the malaria department of the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, said he had never heard of counterfeit Chinese malaria treatments in Africa.

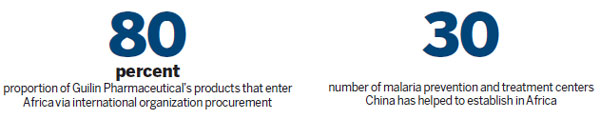

Xia traveled to Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2009 to set up anti-malaria centers under a program announced in 2006 that would see China help to establish 30 malaria prevention and treatment centers in Africa.

The centers benefit patients in Africa, improve the continent's malaria-intervention capacity and promote the transfer of knowledge between clinics and research institutes.

"Chinese-made anti-malaria drugs are popular with Africans and they are generally very effective as well, so I don't understand why some parts of the media printed these stories," said Xia.

"I think the accusations were just a campaign story, which I feel should not be taken too seriously," said Asuman Lukwago, permanent secretary of the Ugandan Ministry of Health.

Kate Kikule, chief drug inspector at Uganda's National Drug Authority, said so far no survey has been conducted to establish that the counterfeits originated in China.

Yu Zhemin, chairman of Guilin Pharmaceutical Co, said his company has not detected any counterfeits of the anti-malaria drugs it markets in Africa.

According to Yu, 80 percent of Guilin's products enter Africa through international organization procurement, and the remaining 20 percent is moved through partnerships with local sales networks.

"The medicines have to pass tests conducted by the local drug authorities and must be registered before hitting the market," he said.

But he conceded that sales channels in Africa are not well regulated. "Some qualified grocery stores also sell anti-malarials," he said.

In the meantime, African governments are taking steps to control counterfeit medicines. The regulatory bodies in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria and a number of other countries are making contracts with companies to supply the drugs or sending their own employees to India and China to assess the efficiency of the quality control process.

Yu said his company's production facilities in China have been visited and assessed by inspectors from countries such as Sudan, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

SMS validation

"While legitimate companies will submit to such processes, shady companies can simply hide and smuggle their fake versions of registered or unregistered medicines into Africa," said Bright Simons, president of the mPedigree Network, a nonprofit organization based in Ghana that provides and aids strategies that focus on combating fake medicines and serialization, or identification codes.

Serialization works by embossing a unique code on each product pack, and mass serialization often involves the cryptographic randomization of these codes to prevent them being guessed or generated by unauthorized people.

Given the prevalence of mobile phone use in Africa, a serialization check via SMS message could be a key method in preventing the sale and use of fake medicines, according to Simons.

He said China has become a major supplier of pharmaceutical products to African countries, especially the anti-malaria treatments that have become increasingly familiar in local pharmacies, and that companies such as Tongmei Laboritoire, a Chinese-invested pharmaceutical company based in Togo, have established manufacturing plants on the continent.

Because many developing countries have weak or poorly functioning national regulatory authorities that are unable to ensure the quality of medicines, the WHO established its Pre-qualification of Medicines Programme in 2001 as a unique initiative to evaluate and monitor the quality of medicines used to treat priority diseases in developing countries in Africa and elsewhere.

"However, although China has begun to use the pre-qualification program as a means of bolstering the reputation of its products, there is a lack of strong programs in African countries to support the anti-counterfeiting efforts of the public health and safety authorities in those countries," Simons added.

The WHO's PQP has pre-qualified 29 anti-malarial medicines and roughly one-third of them are manufactured in China, according to O'Leary.

"The WHO ensures that the medicines procured through the scheme are safe and effective," he added.

However, he said the WHO PQP doesn't cover all anti-malarials produced in, and exported by, China, and the organization couldn't comment on the quality of such medicines.

Also, the WHO has organized training for Chinese manufacturers and regulatory authorities to strengthen production and regulatory practices and ensure that Chinese-made medicines meet international standards.

The responsibility for regulating the pharmaceutical sector remains with the national health authorities of each country, said O'Leary.

"In Africa, as well as in Asia, there is a need for major investment in strengthening the capacities of national health authorities," he said.

Increased collaboration

Kikule urged greater collaboration between the regulatory agencies and governments to ensure drug safety and combat counterfeiting.

Meanwhile, Chinese producers have begun to form partnerships with African pharmaceutical authorities and distributors to facilitate the tracking of their medicines. Anti-counterfeit labels have now been added to drug packaging, making illegal production even more difficult, according to Yu.

The Chinese authorities attach great importance to drug safety, and the regulations concerning exported drugs are in line with international practice, said Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, who refuted the foreign media reports.

Moreover, no efforts have been spared in cracking down on fake drugs.

In June, the authorities in China and the United States launched a joint campaign to close 18 Chinese-language websites selling counterfeit drugs in the US.

Christopher Hickey, director of the US Food and Drug Administration's China office, said the administration hopes for continued collaboration with China in the global fight against counterfeit drugs.

However, investigators were unable to establish where the counterfeits were produced, said Hickey.

In 2007, Chinese police uncovered a massive counterfeit-drug syndicate based in south China, which sold fake anti-malaria drugs in Southeast Asia.

During the probe, conducted jointly with Interpol and the WHO, 24,000 packs of counterfeit Artesunate were seized, according to Chinese media reports.

The drugs were sold mainly in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, according to a suspect arrested during the operation. Malaria remains an endemic problem in those countries.

Ultimately though, concerted multinational action is required to ensure that counterfeit medicines, whatever their origin, are eradicated.

"China is a very important manufacturer of quality anti-malarial medicines and can play a substantial role to help secure safe and quality drug provision in Africa by closely cooperating with global stakeholders," said O'Leary.

Contact the writers at shanjuan@chinadaily.com.cn and lilianxing@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 02/20/2013 page6)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|