The big picture

Updated: 2013-02-25 16:08

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

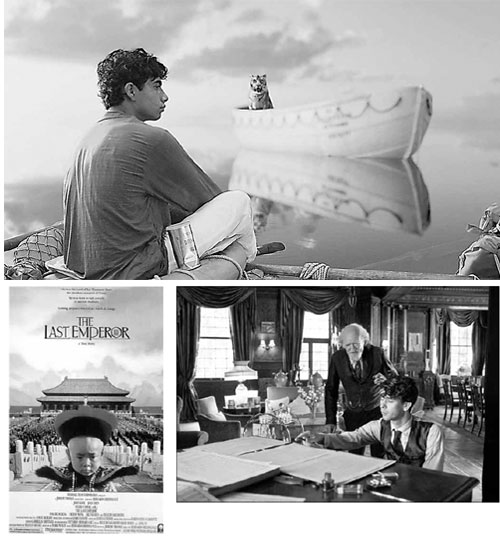

Movies like Life of Pi (top), Cloud Atlas (above) and The Last Emperor (left) sold well on their universal appeal. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Films attain universal appeal through many means, and one of them is a plot with multinational elements. It could be a cheap shot, but when it works, it transcends national boundaries just like the emotions and aspirations it embodies.

There are two general directions for either art or entertainment: One is to go for the specific, and the other for the broad-spectrum.

There are movies that are so personal that they resonate with only a few viewers who are among its target audience. On the other end of the scale, some movies can be understood and enjoyed by virtually everyone in the world.

By no means does this denote quality per se as both have their champions and masters - auteurs like Terrence Malick on one hand and Charlie Chaplin and James Cameron on the other.

Hollywood produces all kinds of movies, and many reach a global market. But little do we realize that many American films are limited in their appeal to domestic audiences, just like releases in most other countries. But, people outside the US equate Hollywood with pictures of global reach because those are the ones that they are exposed to and that speak to them.

China's film industry wants to be the next Hollywood. We want to create screen stories that can sell across the world. But we do not possess the secret formula. We invite Hollywood insiders to our forums and they politely dispense cliches that massage Chinese egos yet rarely shed light on practicalities.

Well, you cannot blame them. Sometimes even Hollywood cannot predict if what they have on hand is a hit or a dud. Before Life of Pi opened, I came upon a story in The Los Angeles Times, in which Fox executives displayed a mix of sacrifice for art's sake and a resignation to the worst possible fate to come.

It turned out the movie grossed $109.3 million in its domestic box-office, but garnered $461.6 million elsewhere, including $90.8 million in China, turning it into a surprise hit. There are many reasons why it made it big in overseas markets, and I would like to highlight one of them: The story and the way it is told is very international.

Yann Martel, the author of the novel from which the movie was adapted, is a Canadian who grew up in a diversity of cultures. Ang Lee, the director, is immersed simultaneously in Chinese and Western backgrounds. The story is mostly Indian, with a nod to the French. (Knowing the French word for "swimming pool" will give you much of the fun for the first 30 minutes.)

In other words, this film is not quintessentially American, which may account for its less-than-perfect critical reception in the US.

Another movie that got downright hostile feedback on its home turf is Cloud Atlas, directed by the Wachowski siblings and Tom Tykwer, a German. The original is by an English novelist, who set one of the six tales in Asia. The South Korea-related plot is not as location specific as San Francisco because it is set in the future and the use of "yellow face" for the male character drew criticism from Asian Americans. But the movie gives the impression it is not about one country, but about the future of mankind.

Like Life of Pi, Cloud Atlas was better embraced in China - mostly because the concept of reincarnation, which is embedded in the structure of the mammoth saga, went down smoothly with the Chinese.

Even though most Chinese filmgoers, who tend to be young, may not believe in Buddhism, the idea that a Caucasian man can be reborn as a black woman is not shocking at all. As a matter of fact, the central character in Mo Yan's novel Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out repeatedly finds another life as an animal, not even as a human.

For a film, going global can take many roads, and one of them is a global story. Of course, a geographically specific tale, say, set in a remote village where people speak a dialect nobody outside understands and customs are so esoteric as to clash with everything we know as acceptable, may also find wide resonance as basic emotions are universal.

Most Chinese movies that have so far gained a global, albeit limited, audience are sold on the strength of specificity and audiences outside China take to them because they are so different and, shall I say, exotic.

In an era of growing globalization, stories that involve more than one country are a natural outcome. If Pi's family did not travel outside India but ran into a boat accident on the Ganges, there would be no French chef, Chinese sailor or Mexican fishermen. It would be a purely Indian tale, at least on the surface, with a narrower appeal.

Now, global stories on screen are nothing new. Both Hollywood and European cinema actually excel in this. Gladiator, the 2000 Oscar winner, is about ancient Rome, but it stars an Australian actor and everyone in the movie speaks English.

The 1974 version of Zorro, which was imported into China and screened to great acclaim, is a French-Italian co-production, starring French heartthrob Alain Delon who speaks English in the version I saw. (It could have been dubbed into multiple languages, as was the norm with European co-productions of that time.) Unbeknownst to us, the story was set in California before it was part of the US. So, if you're a purist, you would agonize over such racially blind casting and myriad inaccurate details.

Chinese audiences experienced a similar agony when The Last Emperor, by Bernardo Bertolucci, an Italian, took the Western world by storm. True, it was shot on location in the Forbidden City and features a Chinese cast, but they spoke English - the version shown in China was dubbed - and there were glaring lapses of authenticity.

So, partly to set the record straight, people in China's showbiz made a television drama of the same story, which most in China felt was more historically truthful. But, unsurprisingly, it failed to gain the foothold so necessary to reach out overseas.

Right now, co-productions are used as a springboard for Chinese stories to travel to parts of the world previously inaccessible.

Sino-American co-productions usually have story components from both countries, as evident in The Karate Kid. These are usually orchestrated by Hollywood, with China playing wallflower.

China's own initial attempt at going global, Thru the Moebius Strip, was met with resounding boos when, in 2005, a Chinese company spent $20 million on a foreign story that was turned into 3D animation, with mostly foreign talents. Even the dialogue was in English.

When a global story falls short, people would say the blunder is lack of idiomaticity.

But Mulan or Kung Fu Panda is not idiomatic either, and that absence of authenticity is partly the reason it became a global sensation.

If we treat culture-specific stories as one genre and global ones as another, we should refrain from using the standard of one to judge the other.

When Weinstein's Shanghai or Warner's The Painted Veil, each with a stellar multinational cast, disappointed, it was not because of , but in spite of, their cross-cultural angle. Some of the stories may indeed fare better with a single, unadulterated culture, but often the story and the story-telling techniques do not jibe with each other. In other words, we have not mastered the art of telling stories to a global audience.

It is interesting to note that Fox considered several directors before Ang Lee, and none of them were ethnically or culturally American. So, deep down, the top brass had a hunch that an international story had better have a helmsman with international experiences.

We all know multinational corporations need business talents who straddle cultures, and obviously it is the same with creative minds.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 02/23/2013 page11)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|