Villagers draw inspiration from a former resident

Updated: 2013-03-15 07:17

By Cui Jia, Wei Tian and Xin Dingding (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Zhang Qiang (right) talks with a resident of Liangjiahe village in Shaanxi province. Zhang is one of 300,000 college graduates who have become village officials since China launched a nationwide program in 2009. He is now assistant to the village Party chief. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

NPC deputy Chang Haixia (right), an assistant to the village chief at Xusanwan village in Gansu province, discusses the government report with her colleague Ma Xuehua. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Contribution made decades ago still a source of pride, report Cui Jia, Wei Tian and Xin Dingding in Shaanxi and Beijing.

On a sunny afternoon, Zhang Qiang took a walk along the dirt road leading to the home of a villager who lives in a cave-house scooped out of the yellow hills of Liangjiahe village in Shaanxi province. "Xi Jinping probably walked along this same road when he was Party chief here," said Zhang, referring to the newly elected president, who took the reins of power on Thursday.

The village of just 360 residents gained national fame when Xi was appointed leader of the Communist Party of China last year. China's new president first arrived in Liangjiahe, which lies in a narrow 1.7-km-long valley surrounded by yellow cliffs, in 1969 as a 16-year-old "educated youth", one of the millions of young Chinese who followed Chairman Mao's call for them to live in the countryside and learn from the farmers. Later, Xi was elected village Party chief, an experience Vice-Premier Li Keqiang shared as a village leader in Anhui province.

"By working as a village official here, I'm following in Xi's footsteps, which puts a lot of pressure on me," Zhang admitted. Although he comes from a hamlet near Liangjiahe, Zhang sat the exam for village officials in Shaanxi province in 2009, following his graduation from Shaanxi Vocational Police Institute with a law degree.

Hard facts

"Officials need to learn the hard facts about rural China so they can formulate practical policies. I was shocked when some officials who came to visit didn't even recognize corn," said the 28-year-old, who signed a second three-year-contract as assistant to the village Party chief late last year.

"Villagers need a firm leader like Xi, and so does China. Zhang is too nice and a bit soft when dealing with village affairs," said Liang Yongcheng. Aged 54, Liang vividly remembers working with Xi when he was just 14. Many of the village's more-mature residents also worked alongside China's new President. "Xi asked us to stick to the jobs we'd been assigned. He didn't like us to pick and choose," said Liang.

Xi is on record as saying that the two groups of people who have helped him most are China's older revolutionary generation and people in this Shaanxi village, where he lived almost half a century ago.

Farming is now prohibited on the terraced land at the top of the mountain where Xi once worked. The ban was imposed to enable the plant life to recover and prevent soil erosion and water loss. It's Zhang's job to ensure village residents receive their subsidy for loss of income.

Nowadays, most villagers have traded their old cave- houses for brick dwellings, although the traditional arched doorways remain. The cave-houses have mostly fallen into disrepair, wild grass has flourished and the old house fronts, composed of dried mud, have collapsed. However, the cave-house in which Xi lived for three years has been carefully maintained and group photos of him with the villagers hang on the wall, indicating the villagers' pride in their adopted son.

While in Liangjiahe, Xi helped to construct Shaanxi's first biogas system. For his part, Zhang built an online learning system for the villagers, so they could acquire knowledge about cultivating apple trees from regular online tutorials hosted by agriculture experts.

"At first, I printed out the tips about taking care of apple trees and handed them out to the villagers, but they just ignored them. Later, I discovered that it was much easier to pass on the information by introducing it in casual conversation with them," he said.

New generation

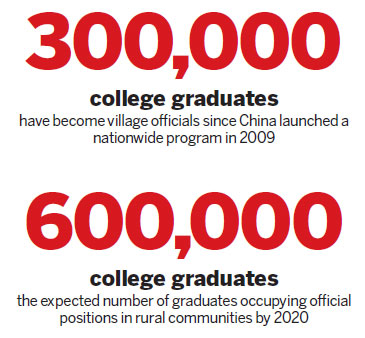

More than 300,000 college graduates have become village officials since China launched a nationwide program in 2009. The number of graduates occupying official positions in rural communities is expected to increase to 600,000 by 2020.

In a bid to encourage more students to work in rural communities after graduation, the central government has promised to recruit more graduates from among those who have taken on leadership roles in the countryside.

This year, 10 to 12 percent of newly recruited public servants will be graduates with experience of working as village officials, according to the State Administration of the Civil Service. In this way, a new crop of future leaders is being nurtured.

In addition to becoming public servants, the graduates, who are initially employed on three-year contracts as assistants to village heads or village Party chiefs, can become village leaders themselves, providing their work has been appreciated by the locals.

Eleven graduate village officials were elected as deputies to the 12th National People's Congress. Gui Qianjin is one of them. Sitting in front of a group of reporters, the 25-year-old looked like the typical "girl next door".

Her delicate fingers, with long nails, played with her white cell phone, while her ponytail and red-framed eyeglasses gave her the air of a recent graduate. However, Gui's youthful appearance hasn't disqualified her from becoming a grassroots village official, leading nearly 1,000 residents in Jiangxi province.

"Being a village official isn't just about planting crops; it's about being able to introduce new concepts to the villagers, and dealing with all kinds of guanxi (relationships)," she said.

Gui's village sits at the foot of Wuyi Mountain, where the rugged landscape is beautiful but makes road-building a difficult proposition. In 2011, Gui watched a group of school pupils struggling through the muddy ridges in the fields, and decided they needed a decent road.

However, dealing with the bureaucracy was dispiriting work. "I asked the town authorities for the money, but they told me to talk to the county government. When I did, I was told that I would have to apply for project funding."

Despite the red tape, the new road was constructed a year later after Gui obtained funding through a special fiscal-support program for public projects in rural areas. "Walking along the road, I feel a great sense of achievement," said Gui.

She later boosted her credentials as a village leader by introducing mushroom farming, which has become a more profitable enterprise than growing rice and is now a stable source of income for the residents. "Being a village official certainly provides a quick introduction to local society," said Gui.

The only downside for Gui is that the salary for such an arduous job is not attractive. "Many of my college friends applied for village-official posts to improve their chances of becoming civil servants," she said.

Country life

Chang Haixia, 26, said a lack of employment opportunities helped push her to apply for a post as a village official. Times were hard when she graduated from college in 2009. "It was during the global financial crisis. Jobs were hard to find and being a village official was a relatively easier option," she said.

Chang, who is assistant to the village chief at Xusanwan village in Gansu province, was two months pregnant when she arrived in Beijing for the annual NPC session and, unlike most of her former classmates, the Lanzhou University of Technology finance graduate dislikes city life, which is partly why she decided to work in a village.

Her teacher recommended that, after graduation, the entire class should work as interns at an insurance company for a month. "First, we received training on how to talk to people, and then we were sent into the streets to persuade passersby to buy insurance plans. Some of my classmates succeeded, but I didn't like it," she said.

Still, she would prefer to work as a civil servant, so as soon as she became a village official she unsuccessfully took two provincial exams for admission to the civil service,

The most difficult part of her routine in the village is persuading the residents to join the social insurance system for the aged in rural areas. "Some were worried that they wouldn't benefit from the system in later life. I went to their homes, even though some pretended not to be at home. I explained the policy to them and told them it was for their own good," she said.

"Sometimes this job can be really rewarding, but sometimes it's just frustrating."

Contact the writers at cuijia@chinadaily.com.cn, xindingding@chinadaily.com.cn and weitian@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 03/15/2013 page7)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|