Ci Xi's China

Updated: 2013-03-28 07:40

By Zhao Xu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

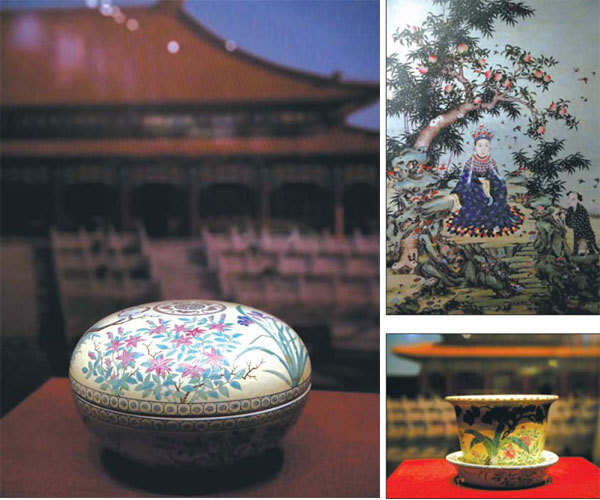

Ci Xi's China Exhibition held at Beijing's Capital Museum displays the Empress Dowager's good taste in her choice of porcelain. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

Porcelain exhibitions are a dime a dozen in China, but this one is bound to interest even the most jaded of museum-goers. Zhao Xu previews the Empress Dowager's china collection.

For 47 years from 1861 and 1908, she ruled China. Her power was envied, and in the seemingly unshakable tradition of male rule, the Empress Dowager Ci Xi of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was legendary, variously described as a combination of ambition, beauty and cold-blooded cunning.

She was loved and hated, having succeeded in seizing and holding onto power while the Qing Dynasty entered its twilight years amid social tumult and turbulence against a changing world.

The public fascination with Ci Xi had been fuelled by various accounts of what she was and how she lived, some more lurid fiction than proven fact. But there is one thing that is concrete and undeniable - the Empress had good taste.

This aesthetic appreciation is reflected in her choice of porcelain, for daily use in court, and now a collection that will be a testimony of her good taste.

A long-awaited exhibition at Beijing's Capital Museum is aiming to do just that. About 100 pieces now on show are all from the capital's Forbidden City Museum, the royal palace and seat of power in China between 1420 and 1912.

The collection starts not with Ci Xi, but with her son, the Emperor Tongzhi, whose birth in 1856 first placed the 22-year-old royal concubine on the competitive path to becoming the country's most powerful person.

A collection of bowls, spoons and teacups launches the exhibition, specially commissioned for the grand wedding of the young emperor in 1872. True to the occasion, coral red and imperial yellow are extensively used, while auspicious icons of bats and magpies adorn the collection. To the Chinese, the homophonic representations of these creatures are supposed to usher in harmony and good fortune.

Another recurring motif is the gourd vine-and-butterfly, symbolizing productivity. With the line of succession already being threatened, this was a priority with the royal family. Unfortunately, historic evidence showed that the wish was not granted.

Tongzhi was the only male heir from his father, Emperor Xianfeng, and he himself died young at the tender age of 19, and left no children. The same fate befell his cousin and successor, Emperor Guangxu, Ci Xi's nephew by her twin sister.

After this first interlude, the rest of the exhibition is devoted to the Empress Dowager, fuelled mainly by her birthday celebrations, which necessitated the production of large amounts of porcelain, at a huge expense and often taxing a cash-strapped treasury.

On these occasions, Ci Xi gave way to her feminine impulses with abandon, opting for the riotous and previously rarely used deep purple and turquoise green while replacing the conventional landscape-and-character motifs with an exuberance of flowers.

Two types of flowers became the darlings of the dowager, says Zhao Congyue, porcelain expert from the Forbidden City Museum.

One was the orchid, which was the name Ci Xi was known by when she was younger, at home. The other was the lotus, sacred to Guanyin, or the Goddess of Mercy, who is often depicted as sitting on an open lotus bloom.

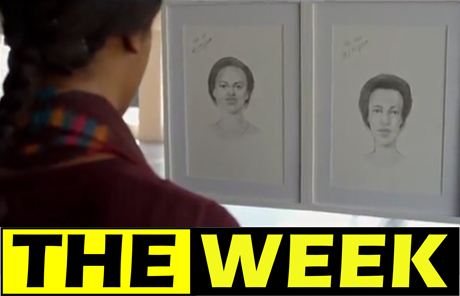

"As she grew older, Ci Xi started to imagine herself as the goddess," says Zhao, pointing to a black-and-white photograph hanging on the museum wall, in which the empress indulged herself in role play by getting up in the full regalia of the goddess.

"The fulfillment of this personal fantasy meant that lotus flowers had not only overtaken entire water surfaces in the royal gardens, but also found their way onto some of the finest china of the time," Zhao says.

The whole duration of Ci Xi's rule, spanning the nominal reign of both Emperor Tongzhi and Emperor Guangxu, coincided with the dramatic collapse of the Qing Dynasty, a process accelerated by her tyrannical, ineffectual and corrupt way of governance.

The inner upheaval and outer encroachment of that time came to be reflected in her own stories.

For the celebration of her 40th and 52nd birthdays, the production of two large batches of porcelain wares was commissioned. Both were delayed, probably due to the severe shortage of skilled artisans during times of unrest.

"In retrospect, the china belonging to Ci Xi represented the last rays of glory for the age-old art, before the fall of a long dark night," says Li Mei, the curator from the Capital Museum.

Empress Dowager Ci Xi died on Nov 15, 1908, after being the pinnacle of power for nearly half of century and spending a total of 300,000 taels of silver (about 344 million yuan, or $55 million in current value) on her insatiable taste for fine china. The end of the Qing Dynasty came three years later, in 1911.

But there is one final clue to who this strong woman was, and it comes from a few Chinese characters that form a seal which appears on everything from wash basins to flowerpots.

"Tiandi yijia chun" means "Heaven and Earth united in spring". According to Zhao, the words came from the name of a building inside the Old Summer Palace, which was burned down by the Anglo-French Allied Armies in 1860.

It was here, between 1855 and 1856, that a 21-year-old Ci Xi spent her pregnancy, basking in the love of her husband, the emperor.

"She remembered that period fondly and looked back on it often throughout her life," Zhao says. "Posterity has long painted her as an empress, a ruler and a villain. But they forgot she was also a woman."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Clockwise from left: Famille rose round box with flower design. A portrait of Ci Xi, dressed up as Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. Famille rose flowerpot and support with flower design on yellow ground. |

(China Daily 03/28/2013 page18)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|