A royal encyclopedia

Updated: 2013-04-02 07:50

By Zhu Yuan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

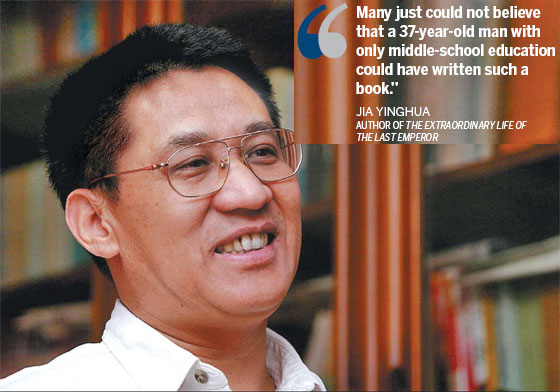

Beijing author Jia Yinghua is still immersed in his studies of the country's last royal family, after four decades of exploration. Provided to China Daily |

|

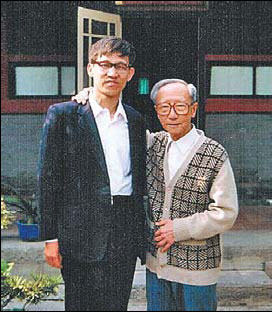

Jia has interviewed royal family members like Pu Yi's younger sister Yun He (above) and younger brother Pu Jie (below right). His prize-winning work, The Extraordinary Life of the Last Emperor. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Jia Yinghua has dedicated more than 40 years of research to China's last emperor. Based on his efforts, he has written about a dozen books related to the final imperial family. Zhu Yuan reports.

With a dozen books about the last royal family under his name, Jia Yinghua is known as a living encyclopedia of the imperial court.

What is particularly noteworthy about his achievements are the efforts he has made in the past 40 years to interview scores of people related to the royal family and collect records and relics.

His book The Extraordinary Life of the Last Emperor was awarded the country's top prize for biographies this year.

Based on his interviews with more than 300 people - either members of the royal family or related to it in one way or another - and based on hundreds of photos and documents, files or other relevant objects, he unraveled one mystery after another about Pu Yi, the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and his family.

His interest started with his childhood relationship with Li Shuxian, Pu Yi's last wife, in 1970. It was three years after Pu Yi's death and Li moved to Dongsi Batiao in east Beijing and became Jia's neighbor.

The widow seldom talked to anyone, Jia recalls. But she was close to Jia's mother, who was one of the more educated women in the neighborhood. Li took Jia to see a traditional Chinese medicine doctor when he suffered from a kidney ailment.

It was at Li's home that Jia first came into contact with Pu Yi's diaries, which were in poor condition. Jia offered to sort out the diaries and mend the manuscripts' worn pages.

In 1976, when Beijing residents put up makeshift tents on the streets as shelters from a possible earthquake, Li stayed with Jia's family in the same tent and told stories about Pu Yi.

"That marked the start of my interest into the lives of the country's last royal family," Jia recalls.

Interest is one thing, writing a book about the latter half of Pu Yi's life is another.

What ignited Jia's interest in writing a book was the request from the editors of a magazine for a story about Pu Yi's life in 1979.

But he did not have the confidence to finish a book until a research fellow from Jilin Academy of Social Sciences cajoled him into handing over the more than 100 pages Jia had spent his spare time writing.

Based on the material, the fellow published a book. This research fellow had humiliated him by saying that Jia was not competent enough to write the book.

"I was enraged," Jia recalls. "I just wanted to let him know that I not only could write the book, but could also produce an excellent one."

That was the turning point. Jia decided to work harder.

In 1981, on his honeymoon leave, he visited Liu Bao'an, a retired man who had once lived in the same room with Pu Yi in Beijing's Botanical Garden.

The nursing home where Liu was staying at the time was in the suburb of Penglai, Shandong province. Both of them clicked like old friends as soon as they met.

The old man gave Jia all the letters Pu Yi had written to him and told him a lot of anecdotes about the last emperor.

His book was finally published in 1989. But the author who had cajoled Jia out of his manuscripts a decade ago sued him for plagiarizing.

Jia faced a lot of pressure at the time.

"Many just could not believe that a 37-year-old man with only middle-school education could have written such a book," Jia says.

He began a tedious process of contacting each and every person he had interviewed to give him a testimony.

With more than 30 such testimonies, Jia won the case after almost two years of court battles.

If his interviews of more than 300 people in a decade taught him how hard it was to write a book, his victory in the marathon copyright trial boosted his self-confidence and made him realize the importance of getting hold of exclusive material and historical records.

The interviews Jia conducted and the first-hand historical documents, facts and relics he has collected in the past four decades made him an expert on the country's last royal family.

In his own archives, he keeps nearly 1,000 photos related to the last emperor's family, hundreds of hours of discs about his interviews with family members and documentaries he made about some historical figures of the late Qing Dynasty.

With these, he has uncovered some stories that were never known before and also rectified some hearsay.

Pu Yi was born on Jan 14 of the lunar calendar in 1906, while Emperor Daoguang died on the same day in 1850. To avoid bad luck and also show respect for the late emperor, his birthday was said to be one day earlier. So his birthday was celebrated on Jan 13 every year.

There was a saying that Pu Yi's father said "kuai wan le (almost finished)" when young Pu Yi cried at the ceremony to crown him emperor. Even Pu Yi himself wrote in his biography that his father said "kuai wan le". The Chinese character "wan" was later interpreted as portending the end of the Qing Dynasty.

But, Pu Yi's younger sister told Jia that her father never said that. What he said was kuai hao le which also means "finish soon". But the character "hao" does not carry the ominous meaning.

Retired, Jia is still immersed in the study of the royal family. He says that he doesn't consider himself talented but he is obstinate in pursuing what he believes is worth his effort.

Contact the writer at zhuyuan@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 04/02/2013 page19)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|