East meets West on drafting table

Updated: 2013-04-05 12:02

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Line and Space worked closely with Legend Company on "The Two", a sales office in Xiamen designed to eventually become a community art building. Provided to China Daily |

Western architectural firms in China find steady business, more leeway for creative design and challenges, reports Kelly Chung Dawson from New York.

When news broke in late 2012 that developers in Chongqing were building a near-exact duplicate of British architect Zaha Hadid's Wangjing Soho development in Beijing, her reaction was surprisingly magnanimous.

"That could be quite exciting," she said of the potential for another developer to add innovation or improve upon her work. Soon afterward, her firm issued a threat of litigation against the developer, Chongqing Meiquan, which denied the allegation and launched an advertising campaign proclaiming: "Never meant to copy, only want to surpass."

The Chongqing structure is scheduled to be completed in 2014, a deadline that has both the alleged copycat and its inspiration racing to finish construction first.

Hadid is one of a number of high-profile Western architects commissioned to work on splashy Chinese projects, including state-of-the-art entertainment and arts complexes, airports and luxury hotels across the country. Completed in 2010, Hadid's Guangzhou Opera House employs a revolutionary asymmetrical design. Rem Koolhaas' head-turning design for Beijing's CCTV building, completed in 2008, was labeled "maybe the greatest work of architecture built in this century" by the New York Times.

Less reported on has been the wave of small- to mid-size Western architectural firms that have found steady business designing less glamorous projects like multi-use retail and business centers, private residences and other structures, feeding a demand for growth and construction in lower-tier cities.

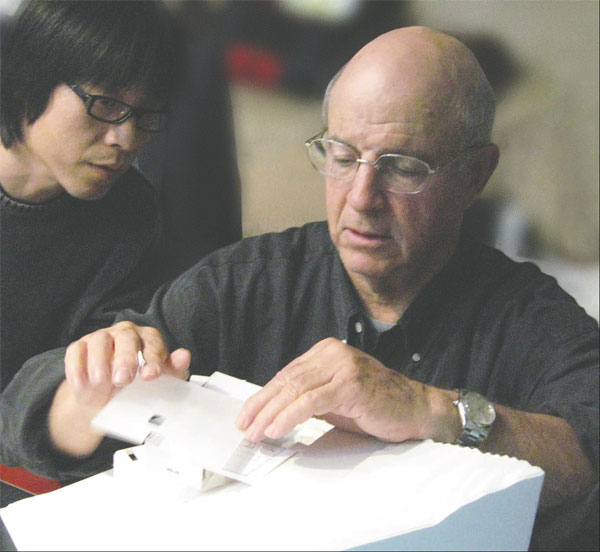

"It's about demand and supply, and everyone is trying to get a piece of the pie," said James Zheng, head of the China operation for Goettsch Partners, a mid-sized firm based in Chicago. "They're all in China now, because everyone wants to offset the lack of work in their domestic markets."

Many US firms also say that they have more leeway in China to experiment with creative design than in their risk-averse home market, which has been slow to recover from the economic recession. With that design freedom, some architects say, come challenges for US and Chinese companies, as well as local architectural firms employed to smooth such collaborations. Potential hurdles include cultural unawareness, occasionally unprofessional Chinese partners and major differences in local building practices and codes.

Chinese developers choose to contract Western architectural firms for a variety of reasons, most notably the prestige that a Western name can bring to a Chinese development. Developers are eager to publicly flaunt their ability to spend astronomical sums to entice Western companies, whose very participation can be seen to legitimize a Chinese project. For Western firms, high-paying splashy projects are also enticing.

"Obviously there's the market, and the prestige of doing work internationally," said Kevin Kudo-King of Olson Kundig Architects, a mid-sized firm based in Seattle. "We like being an international firm. And from a selfish point of view, we do feel that doing international work makes our work better. We want to learn about different cultures and incorporate local ideas of architecture into our work, and to be inspired to create something we wouldn't have created otherwise."

To Alexander Wong, a Hong Kong-born architect who studied at Princeton University and has worked with Western firms on several projects in China, the question should be, "Why do so many developers all over the world still turn to Western architecture and design firms?"

"Western civilization invented modern architecture, which made a tremendous impact on the course and history of modern civilization, particularly with respect to the development of global urbanism," said Wong, whose projects include the "avant garde cinema" UA Shenzhen, which received a USA International Design Award in 2010. "So perhaps it may not be that much of a surprise that the 'inventors' have at least a slight advantage."

More importantly, he said, the long standing tradition of Western architecture has resulted in a stronger educational infrastructure in Western countries.

Chinese culture has also lagged in "brand building," Wong said.

"One needs to study not just the history and developments of the country in terms of economics, culture, sociology but also governmental policies and design as a national investment. And without a doubt, architectural design is a brand! So [a government] must nurture such brands nationally or at least have a vested interest in doing so on that level before one will see any results at all."

Many of the higher-profile contracts with international architects were awarded by Chinese government agencies. Hadid, for example, won a regional government-sponsored competition to build the Guangzhou Opera House. She was the fourth "winner" after three previous selections had been discarded by local government for undisclosed reasons.

Designing in China

Designing for the Chinese market can feel liberating because in contrast to US conditions, the Chinese government seems determined to push construction growth, said Clark Manus, CEO of Heller Manus Architects in San Francisco and president of the American Institute of Architects.

"It has been extremely refreshing for us to explore new ideas in China that we would not have been able to do in San Francisco due to planning and zoning restrictions," he said. "They're able to be more forward thinking in some ways; simply put, the government is making things happen."

He noted that talk of building a US high-speed rail has been going on for 10-15 years. "In China, they're able to put their money where their mouths are and deliver things we should do in the US but don't have the money or the political cohesiveness to deliver."

Line and Space, a small Tucson, Arizona-based firm that has done 79 projects in China, is working on two with Legend, a Chinese development company.

"They give us an exceptional amount of time to develop our design ideas, have provided strong critiques and supported our investigations and studies of site situations and program considerations," said firm founder Les Wallach. "I can say without reservation that our clients understand and respond to abstract conceptual ideas better than any client we have had previously."

In 2006, ZK Real Estate Development Co hired 10 Western architectural firms to design 78 unique residences for a 46-acre luxury villa development outside Shanghai called the Zhongkai Sheshan Villa project. Stuart Silk, head of a 21-person firm based in Seattle, was commissioned to create nine residences. The Chinese developer hired a Harvard University-educated architecture consultant, Wang Qian, who encouraged the Western firms to run free with their ideas. The project was an opportunity to go big, Silk said.

"They really encouraged us to use our best judgment," he said. "They felt they had hired talented architects, and they made it clear that they didn't want us to feel hindered aesthetically."

But as the process continued, the developer and the consultant Wang began to clash, Silk said. Wang and other local architects who had helped oil the early days of the project seemed to lose control, which became "driven by people who didn't know what they were doing," he said.

"There were too many moving parts. They did everything an American developer would not have done; their original aspiration to do all these unique designs was enlightened, but no Western developer would have done this project, which was a recipe to lose millions of dollars," Silk said. "In the end, I was disappointed. It took a few years more than we thought it would for them to complete the buildings, and they only kind of look like what we designed."

Olson Kundig was also hired to design eight residences for the project. Kudo-King, who served as project manager for Olson Kundig's portion of the development, also believes that the developers began with the intention of nurturing strong design.

"The developer was still learning the process," he said. "Part of it was that the project began in 2004, and everyone in China is on a learning curve. There was a loss of focus."

Wang Qian and ZK Real Estate Development didn't respond to requests for comment.

Fearless about risk taking

Zhonggui Zhao, a Yale University-educated partner at Zephyr Architects in Beijing, said such clashes with Chinese developers and the government aren't isolated.

"On the one hand, you can say that the Chinese developer/government agencies respect the architects," he said. "They are fearless about risk taking. They have helped many Western architects to realize their dream [designs], which would never have been built in their home countries. On the other hand, they are very unprofessional. Most of them don't care about craftsmanship and building quality. That change will take years."

But Goettsch Partners' Zheng notes that there has been a dramatic improvement in the sophistication of developers and clients in the last 10 years.

"They've seen more projects outside China, and these days they're talking in the same language about efficiency and sustainability," he said. "They're quickly picking up speed about what makes design good or bad. The changes have been drastic, and the gap is shrinking in terms of both clients and the skill level of local Chinese design firms."

While developers remain a wild card in some respects, local Chinese design institutes (LDI) and architectural firms have also improved significantly through collaborations with Western firms, Zhao said. The local design institutes are employed for their expertise of local codes, engineering expertise and to translate both language and cultural differences.

Bridging trust issues

Sern Hong Yu, China regional manager for California-based 5+designs, which was recently commissioned to design the expansion of the China World Trade Center, said local firms are often used to bridge trust issues between the developers and the designers.

"It is very difficult to have the client approve of having a foreign firm work on [anything beyond the design], as the client very often thinks the foreign designers do not understand the local culture and habits of its target consumers," he said. "As such, the foreign firm more often than not, loses control of the project and the end result is a project which ends up nothing like what was envisioned during the early concept stages. However, LDIs are now more competent and giving foreign firms a run for their fees. This provides us with better quality support in ensuring that the project will be properly built."

Wong said that Chinese developers are often subject to rapidly fluctuating market conditions.

"Due to forever changing conditions in the market [which are highly volatile and in constant flux] that are beyond the control of the Chinese clients, Western architects do have to adapt and even drastically change their designs, perhaps considerably more so than if they were designing in other less volatile markets," he said. "[As a result], US firms may find their clients extremely difficult to work with. But without making this sound like I'm conjuring up any excuses, almost any Chinese person will tell Western friends that the cultural differences between East and West are considerable."

Notable differences that have posed problems for Western designers in China include the requirement of feng shui-friendly design, a reliance on native building materials, far less rigid safety standards, and varying electrical, plumbing and structural systems, Kudo-King said. But many of the differences simply require Western designers to adapt to new ways of thinking about things, he said.

Some cultural differences have proved insurmountable, said Li Xiangning, a professor at Tongji University's College of Architecture and Urban Planning in Shanghai.

"Chinese developers seldom work with US firms to develop residential buildings because people in the two countries have different taste and living habits," he said. "US architects do not understand the layout of China's houses, nor the building codes. For example, they do not understand why Chinese people require the houses to face the south. As a result, in the field of residential design, there are few architects from West, and almost no foreign firms specializing in large-scale residential building design."

Chinese architectural firms still dominate the market in lower profile projects and smaller cities, Li said.

But as Western firms continue to stream into the Chinese market, the field will only benefit from the creativity that such collaborations inspire, Kudo-King said.

"There's this cross-pollination of ideas, where ideas that originate in both cultures come together to create something unique and truly special. I think there's a realization today that there needs to be a clear, shared vision. We're seeing that more and more."

Contact the writer at kdawson@chinadailyusas.com

Yang Yang, Chen Nan and Gan Tian in Beijing contributed to the story.

|

Line and Space's design of "The Two" sales office. Provided to China Daily |

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|