Cosmic dream drama

Updated: 2013-04-15 12:48

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

If one can control one's dream, one can control one's destiny, runs a line in Stan Lai's A Dream Like a Dream. To those who stage this epic play, it is a fitting metaphor, while for theatergoers the work is so dense in texture, so exalted in wisdom, it demands absolute surrender.

There is no doubt in my mind that A Dream Like a Dream is a major milestone in Chinese theater, possibly the greatest Chinese-language play since time immemorial. It is just not the most accessible play from Stan Lai. The transcendent wisdom and innovation have combined to create a cultural event, as well as a viewing experience that is at once singularly challenging and endlessly rewarding.

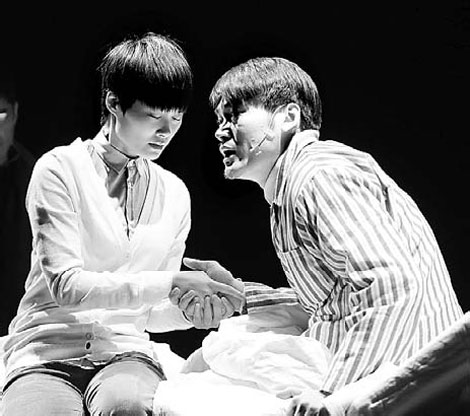

The first run of this new production in Beijing, which will end on Sunday, has opened a floodgate of responses, from amazement to bewilderment. The inclusion of pop stars in the cast, while bumping up attendance, may run the risk of skewing attention from the serious to the frivolous, as borne out by the paparazzi-like behavior of some audience members. Still, I could not help but marvel that such a monumental work has been produced at all, without any government or corporate sponsorship.

A Dream Like a Dream arrives on the heels of such instant classics as Secret Love for the Peach Blossom Spring, The Village, among others. Stan Lai, the Taiwan dramatist and impresario behind these masterworks, is praised for his uncanny ability to bring together the highbrow and the lowbrow - an almost impossible task in a market where what wows and what sells are often miles apart.

Lai has admitted that A Dream Like a Dream is his most personal work to date. At the prohibitive length of eight hours (including two 20-minute intermissions), plus the extra cost of revamping the theater to its requisite configuration, the play is such a big financial risk that kudos should be given to all those who are crazy enough to invest in it.

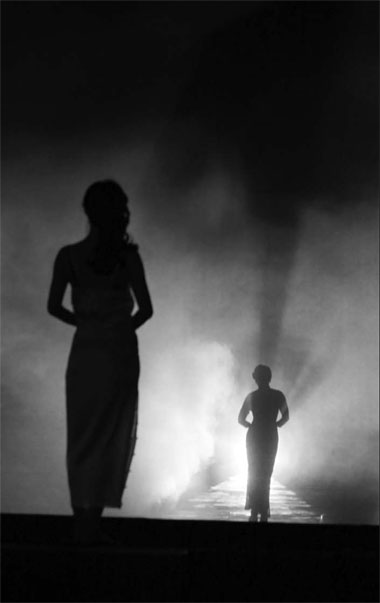

The play is built on a massive and intricate plot structure, but is seamlessly commensurate with its themes and staging. While the clockwise circumambulation is a constant visual motif, the story within another story (within a third story actually) goes backwards, each one more elaborate.

Doctor A's tale is set at the current time, and from her conversation with Patient No 5 we travel back to the 1990s. His story unfolds and traverses all the locations. In Paris, he falls in love with a Beijing woman whose traumatic escape from her hometown provides the first layer of historical texture. Later, the couple tour Normandy, where they chance upon a portrait of a French diplomat and his Chinese wife. The patient, whose is not given a name, tracks down the mystery Chinese woman, now on her deathbed, and coaxes out her colorful life story.

Life and death are obvious themes. So are holding on and letting go. Patient No 5 suffers an inexplicable illness and is therefore acutely aware of his mortality. In a sense, he finds a vicarious new life through someone else, someone he feels an immediate bond with, even though he does not know that person. The way the female doctor implores him for his story is very similar to the way he repeatedly beseeches Koo Hsiang Lan, the Chinese courtesan who marries into a French aristocratic family in the 1930s.

There are numerous parallels of this kind. Some stand on religious underpinnings, such as reincarnation, and others are more philosophical, as if life is a spiral - you encounter different people and happenings, yet the similarities are so eerie you are eventually faced with what's constant in life.

Koo Hsiang Lan holds on to her past just as Patient No 5 perseveres in his quest for truth. They form the central tango in the ensemble, which transcends the confines of time and space. Koo represents the female side, each generation shackled by traditions, such as serving male masters, kowtowing to a suffocating system, or simply following parental advice to date the right man.

Eventually, each finds herself on a mission to seek freedom from cages gilded or rusty. Even when Koo seems happy, as with her bohemian friends in Paris, she is still a slave of her husband, whose family fortune sustains her lifestyle. On the male part, Patient No 5 and the Count can be read as two phases of the same personality. Both are stricken by the enigmatic power exuded by a strong female figure rather than a flesh-and-blood woman. In a sense, they have fallen for the fantasy of a woman.

Noticeably absent from this equation are such melodramatic ploys as betrayal or reconciliation. Each character is essentially fighting a lifelong battle with himself or herself, trying to figure out one's own identity and, on top of that, one's past and future.

That, plus the unique seating arrangement, makes it easier for the audience to project themselves onto the rotating gallery of characters. For those sitting in the swiveling chairs in the "lotus pond" - the on-stage sunken area in the center - the proximity with actors, plus the ease with which the characters can be related to, facilitates an immersion, or "qi" in the Chinese scheme of things, something you can feel but is hard to describe. The opening scene of people walking in a circle, ritualistic as it is, induces an almost knee-jerk reaction because, as some reveal afterwards, they see their lives hurrying by, leaving little time for reflection.

Ultimately, it is an inner journey - a spiritual journey through time and conflicts - to reach the destination of a higher consciousness, a state of being at peace with both the outside world and with oneself.

Time is a concept ingeniously manipulated and masterfully presented in this play. The monotony of life is epitomized by the frying of eggs, each repetition with one more actress playing the role. But the most brilliant touch is the meeting of two actresses playing different phases of the same person. It is, literally, an out-of-body encounter.

Time may be cyclical, but the legacy of each generation exerts its impact on future generations. The final 10 minutes feature the deaths of all three main characters, each one bequeathing something positive or negative. Again, this can be called qi or energy. Abstractions so esoteric gain an emotional heft through the sheer force of Lai's imagination and the actors' total trust in the master and their commitment to the project.

A Dream Like a Dream may be the most cosmic piece of theater in the Chinese-language canon. While all plot points are time and location specific, they can be substituted without losing relevance. Neither does it require familiarity with Taoism or Buddhism to get to the heart of the work. However, it may yield to varying interpretations. Where one sees life as it inevitably can be, another may resonate with the efforts to steadfastly swerve from the pattern of vicious cycles, or to take a load off the historical baggage, and rise above the banality of life as it seems so preordained.

Such richness is rare except in a work of great scope and depth and crafted by someone who has reached an artistic height that may baffle many an ordinary viewer. Future generations may have a field day dissecting the minutiae of this piece, but some of us can proudly say we were there and we saw how the master worked his miracle. Like the Elia Kazan-directed version of A Streetcar Named Desire or Maria Callas' Lisbon Traviata, this Dream is going to stay with us for a long, long time.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

High-profile pop stars Li Yuchun (left) and Hu Ge give unexpectedly impressive performances that belie their inexperience in theater. Photos provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 04/13/2013 page11)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|