China hands' first impressions often strongest

Updated: 2013-04-19 11:44

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

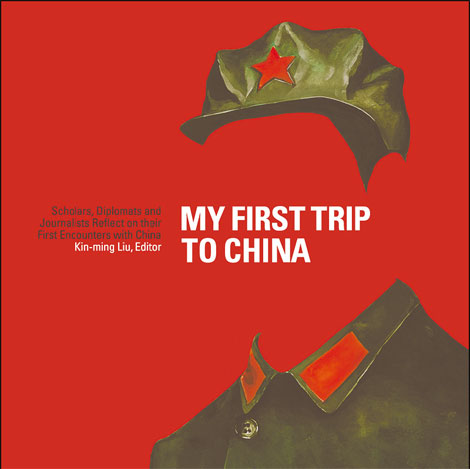

My First Trip To China is a book with accounts of 31 China-hands including Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Ian Johnson; Sidney Rittenberg, the only US citizen to join the Chinese Communist Party in the 1940s; historians Ezra Vogel and Simon Leys; Fortune China editor Thomas Gorman; and Lois Wheeler Snow, an actress and the widow of "Red Star Over China" author Edgar Snow, about their trips to China. |

When Kin-ming Liu read fellow journalist Richard Bernstein's 2010 farewell column in the International Herald Tribune, he was struck by Bernstein's recollection of his very first trip to China in 1972. As a native Chinese, Liu had long been interested in the way foreigners viewed his homeland, and Bernstein's column convincingly laid out the enduring power of a first impression, vivid even as he bid goodbye to China decades later.

Liu was startled to discover that several other journalist friends had accompanied Bernstein on that 1972 trip and shared strong feelings about the experience. He soon realized that the topic might encompass the first impressions of not only journalists, but diplomats, businessmen and other China hands. Through 2010 he published 51 accounts on the website of the Hong Kong Economic Journal, his employer at the time. Thirty of those stories appear in a new book, My First Trip To China, from noted China experts including Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Ian Johnson; Sidney Rittenberg, the only US citizen to join the Chinese Communist Party in the 1940s; historians Ezra Vogel and Simon Leys; Fortune China editor Thomas Gorman; and Lois Wheeler Snow, an actress and the widow of Red Star Over China author Edgar Snow.

"Even though I'm Chinese, I'm a student of China too," Liu said. "These are dramatic, compelling stories, and many of these contributors will be familiar names for China watchers, who have never sat down and told their own stories in a systematic, thoughtful way. China has changed so much, but it's a vast, complicated place, and to read about the first experiences of these longtime China experts is really fascinating and valuable for contemporary first-time visitors to China as well."

In the book's foreword, Asia Society Director Orville Schell writes that the early China explorers were of a certain breed, motivated by the powerful draw of a forbidden place.

"While so much of the rest of the world had been blurring its boundaries during the early stages of 20th-century globalization, here was China, defiantly maintaining its revolutionary identity and isolation, becoming not only a terra incognita for most of the world, but also conferring on it an air of mesmerizing impenetrability and unpossessability. Its haughty detachment, fierce dedication to self-reliance and abject refusal to surrender to the outside world's pressure paradoxically made it a strangely alluring place at least for some of us! This book chronicles the accounts of such people remembering their first passage to China. What I think drew us powerfully was China's apparent disinterest in us."

He compared these early outliers to explorers of earlier eras, unable to conquer unmapped territory and therefore drawn to a civilization that felt diametrically opposed to their own.

"I could go to the jungles of Burma, but I couldn't go to China," he said. "It was this great question mark: What were they really doing? And would it cohere?"

Due to the difficulty of visiting China at the time, the group was self-selecting, Liu said.

"Many of the early people who went were open to China's ideology," he said. "They liked the idea of China, and I would say that none of these early visitors had ill feelings. They went with good will, and while some of them experienced subsequent events that changed their minds, they all went with very open minds."

When Schell arrived for his first visit to China, in 1975, he found that his previous time in Hong Kong studying both the language and culture hadn't prepared him at all.

"When I finally got to China, I was so utterly shut out and excluded," he said. "I found interaction with ordinary Chinese almost impossible. I didn't know how to explain that. A lot has changed since then, obviously, but I think reading these accounts you can see what an immense gulf existed between China and the outside world - and in many ways, there continues to be a gulf. You also see exactly how much baggage we Westerners brought to our own interactions with China, our own pathologies in looking at and understanding the place. This book is an incredibly interesting slice of intellectual anthropology, and I do think that people who came into the story so early do perhaps have a better understanding of that part of China that to this day remains unchanged, even in the midst of extreme change."

For Edward Friedman, an author and political-science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, two months in 1978 studying what he believed to be an authentic Chinese village, proved how difficult it was for any outsider to observe the "true China," he said. After painstakingly gathering and documenting data, Friedman and his fellow researchers discovered after their departure that they had been observing a model village set up specifically for outside eyes, he recounts in his essay "Finding the truth about rural China."

"To me, the major takeaway is: Your eyes are pretty close to useless, in understanding how China actually works on a first-time visit," Friedman said. "What you think you see is a surface of things, and the only way you really learn about China is with your ears. If you don't have Chinese friends telling you what things really mean, your eyes are misleading.

"When I read reports of people who go to China for the first time today and then come back and tell you what the truth is about China, I can't help but feel that it's arrogance and stupidity. China is not a superficial place without depth or contradictions. I hope that this book makes clear to people that they should not ever think they're so clever that they can go to China once and truly understand."

In the essay "From Air Force One to Lao Gai," journalist James Mann writes about visiting China in 1984 aboard a press plane accompanying President Ronald Reagan. The highly choreographed political visit gave him only a sliver of the big picture, he recalls. He later wrote about that gap in his 1997 book Beijing Jeep: A Case Study of Western Business in China.

"Even after people have lived in China for a long time, it's still not the same as the understanding of an ordinary Chinese," he said.

"After all, the expats always know they can get on a plane and leave, and that will always be at the root of their interactions. Tracing that history and the individual experiences of many of the people included in this book gets at a sense of nostalgia for the early days of that relationship."

The scale of change that has occurred in the intervening decades provides a vastly altered context for the book, Liu said.

"If I had put this project together twenty years ago, it might have been a very different book," he said. "The experiences might have been the same, but their interpretation today as a result of the rise of China, might have been very different. It's an interesting way of looking at the history of an important relationship."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|