Ancient art given new life

Updated: 2013-04-19 08:19

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

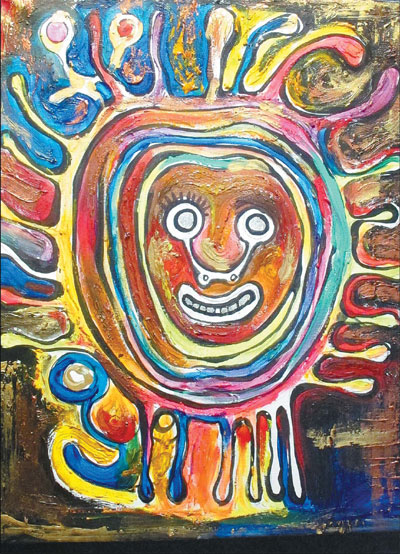

An oil painting displayed at the Grassland Culture Communication Center in Hohhot, the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

The cliff paintings of the Yinshan Mountains represent thousands of years of history, and now an antique collector turned gallery owner is on a mission to honor their artistic legacy. Wang Kaihao reports from Hohhot.

Pilgrims to the lama temple Ih Juu in Hohhot, capital of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, may not notice an old bookstore nestled in a corner of the square facing the place of worship. The bookstore's battered facade allows it to blend into the street, giving the impression it has stood there for many years. However, if visitors stumble upon the store and find their way up to the second floor, they will be amazed to discover a selection of fine arts.

Dozens of colorful, flamboyant paintings line the corridors making the space look like something conjured up by Salvador Dali. But the paintings have not been collected only for their aesthetic beauty, but to preserve an important cultural tradition.

Hohhot-native Zhang Haibo, a 43-year-old of the Hui ethnic group, established the Grassland Culture Communication Center before this year's Spring Festival. He launched the project in an effort to revitalize the tradition of the ancient paintings that can be seen on the cliffs of the Yinshan Mountains.

Thousands of cliff paintings in Inner Mongolia's Bayannur provide a glimpse of nomadic people's life in Northern China dating from 10,000 years ago to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), which was established by the Mongols.

Though they were first recorded in the 5th century, serious research on the paintings only began in the 1970s. Bayannur municipal government announced in late 2012 that the paintings are among China's new candidates for the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites.

"These cliff paintings are our lost collective memory," Zhang, once a successful antique collector, says. "The histories of Huns, Turks, Mongols and many other people are embedded there. As our country endeavors to make the cultural industry boom, I think it is time to do something more meaningful."

He gathered some local artists and asked them to use modern methods to create new works inspired by the simple lines and circles painted on the cliffs. He also invited about 10 artists from Mongolia and Russia to join his 30-strong artistic adventure squad, explaining the project "has to cross the national boundary for a creation that concerns the whole of the grassland".

When oil painter Khaimchig Zayat from Mongolia came to China six months ago and visited Yinshan for the first time, he was astonished by the cliff paintings.

"They look like aliens, but I immediately feel like I can communicate with the painters through time travel. The inspiration seems to have mixed with my blood," he says.

Zayat believes in shamanism. He says the cliff paintings become colorful when he closes his eyes. Shamanism is practiced by many ethnic groups in Northern Asia.

"It is art, but it is also a communication between me and gods," Zayat says.

Under his pen, the abstract lines change into colorful images with metaphysical themes to represent Mongolic philosophies and universal views.

"His heart is like a lens," says Zhao Shulin, a Beijing-based fine arts critic who has high praise for Zayat's work. "The world in his eyes is more harmonious and natural. His works have got rid of artificial vestiges and gone beyond space and time.

"Mongol culture greatly contributed to Western civilization during its expansion in the 13th century, and on the other hand it also absorbed Han people's philosophies during the Yuan Dynasty," he says. "The arts are deeply rooted in that cultural background and reveal many common human values and will be easily accepted by both the West and the East."

Zhang adds that only the artists who were born on the grassland are qualified to visually decipher the ancient code.

"It is not because others are not skillful enough, but some subtle emotions can only be felt by grassland inhabitants."

Traditional Chinese paintings portraying Inner Mongolia's magnificent grasslands have long been prevalent, but Zhang wants multiple art disciplines to depict the area.

"This is not a place to begin a school of painting and demand our newcomers follow certain disciplines. I don't want it academic. Independent artists have more freedom to express their thoughts and not be restricted by a certain style," Zhang says.

Bainbolg, a 33-year-old Chinese painter of the Mongolian ethnic group, agrees. After running an independent studio in Hohhot for several years and becoming fed up with art museums' rigid standards, he joined the center earlier this year. He relishes the opportunity to work with artists from abroad.

"Many domestic painters think too much about how to take part in art exhibitions and leave little time to reflect and draw something from the bottom of their heart, but I find the painters from Mongolia are the opposite," he says.

"I now place little restriction on ways to express myself through art and I freely convey my understanding of our traditions. That is the essence of arts, which is especially precious in this quick-fix society."

The artists also refer to the surrealist tradition to illustrate the Mongol people's totems. Bainbolg says they will use any form that reflects their spirits and beliefs.

Zhang plans to organize an exhibition of modern pieces of Yinshan cliff paintings in Bayannur in June, and is even considering touring the country.

Lhkagvadorj Sukhbaatar from Mongolia is a member of a national association of traditional Mongolic painting, which involves 250 top-level painters in that country. He is attracted to the atmosphere in Zhang's place and is looking for more inspiration in Inner Mongolia.

According to Sukhbaatar, his paintings using mineral dye on cloth have some similarities with thangka in Tibet, but also bear unique characteristics in images and styles. A painting will usually take half a year to finish.

Sukhbaatar says an arts academy in Mongolia produces 12 painters every year who can practice this kind of traditional painting, but it is not enough to keep the skill alive because fewer young people are interested in learning.

He therefore hopes to combine the efforts of China, Mongolia, and Russia to draw more international attention to better protect this traditional art, a campaign he is launching from Hohhot.

"Who knows what will happen? Though my energy is limited and I am devoted to my own work, maybe I can also have some Chinese students one day," he says.

The project has gotten off to a good start, and Zhang feels confident his ambition to gain international interest in the work will be a success.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Oil painter Khaimchig Zayat from Mongolia studies a rubbing piece of the Yinshan cliff paintings. |

(China Daily 04/19/2013 page18)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|