A teacher for life

Updated: 2013-05-07 07:11

By Li Yang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

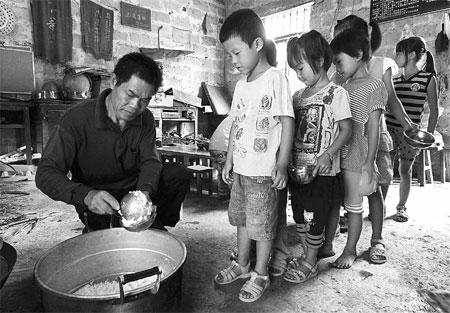

Pan Shanji fills the students' bowls with rice during lunch. Apart from teaching, Pan also cooks lunch for the students every day. Photos by Deng Keyi / for China Daily |

|

Pan Shanji teaches at Dayandong education point in Guzhai Mulam ethnic town in Liucheng of the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. |

Pan Shanji was the first high school graduate from the remote Dayandong village, and has spent the past 34 years as a committed educator, passing on his knowledge to children who have few other opportunities for schooling. Li Yang reports from Liucheng county, the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

Pan Shanji has taught about 200 students over his 34-year teaching career, and although not one of them made it to college, he is very proud of all of them.

"My students are the first batch of people from three local villages who have dared to leave the mountains to look for jobs," Pan, 53, says.

Pan, a member of the Mulam ethnic group, is the only teacher for 12 students aged from 6 to 9 years old at the education point in the mountainous Dayandong village in Guzhai Mulam ethnic group town in Liucheng county, the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. He teaches Chinese, math, sports, painting and music.

Education point refers to the grassroots education unit in villages.

The three villages, with about 70 families and 300 residents, are the most remote in Guzhai town. In the 1940s, their ancestors fled to the mountains to avoid the approaching Japanese invasion and settled there. The average annual income per family is less than 1,000 yuan ($159). They cultivate small patches of farmland in valleys and live a self-sufficient life.

Pan is the first high school graduate in Dayandong village, which makes him feel responsible for helping the illiterate villagers.

"I have four younger sisters who gave up their only chance of schooling for me. My father lost his chance to join the army because of illiteracy in the 1950s. He was so worried when he worked as a groom for a local production team in the 1960s because he could not even count. In the early 1970s, when he worked as temporary worker at local railway construction site, he often cried at night, silently, because he could not write home for three years and he was too shy to ask for help. So I tried my best at school."

Pan took corn and sweet potatoes with him to his high school in Luoya town where he was a boarder in 1977. He says his headmistress Mo Rongxuan encouraged his studies, telling him: "You are the student from the mountain. I hope you can focus all your energy on studying. Don't be distracted by other things."

The former village Party secretary convinced Pan to return to the mountains to teach after he graduated from high school.

But four years after Pan returned, the village Party secretary died, leaving his 8-year-old daughter and widow in miserable circumstances.

"I made up my mind that I must marry her (the daughter) when she grows up to take care of her. So I waited for that time and married her in 1988 when I was 28 years old, quite a late marriage age for men in the village."

His wife has been paralyzed by femoral head necrosis for 20 years. "We needed the money to take care of my sick father at that time. He died several years ago. Now my elderly mother is also ill in bed. My daughter and my son are very thoughtful. My older daughter works in Liuzhou after graduating from a vocational school. Her brother, now in junior middle school, has also decided to start working as soon as possible. I will try my best to take care of my wife. This is a promise I made to her when I married her," says Pan, beginning to get emotional.

"Let's talk about something happy." He changed the topic to his work. "When I hear the children say 'Good morning teacher' to me everyday, I forget all miseries of my life," he says, with a big smile on his face but with tears in his eyes.

Today, all of his 12 students are left-behind children. Their parents are former students of Pan's who now work in Guangdong as migrant workers.

Pan cooks the "free lunch" for the students at school every day, a project sponsored by the State that gives each student a 3-yuan lunch subsidy, making him more like a father than a teacher to the lonely kids.

Pan tries to inspire the students with awards, a pencil, a notebook or little snacks. "These children are very poor. I have to make up for their loss of family education and help them develop their character and sense of responsibility and teamwork," he says.

It takes the children an hour and a half to travel to school in the morning. Pan often returns home with them after school. To make sure they have enough strength to go home, Pan cooks porridge for them in the afternoon.

He refuses to be transferred to other schools, because the children in the three villages would have to go to the school in the center of town. It is too far to travel and too expensive for many of the children to board there. Pan says if he retires, some of these students will drop out of school.

"I never miss a class and will work here until the end of my life. This is a promise to my wife's father and my middle school headmaster. No soul deserves to be wasted."

In 2007, to avoid missing his classes and save money for his family, Pan treated his serious lumbar vertebrae hyperostosis with medicine, ignoring the doctor's advice to undergo an operation, resulting in serious damage to his right leg.

The interview is finished before noon. Pan hurriedly hobbled his way back home along the bumpy lane to feed his sick wife and mother.

Contact the writer at liyang@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 05/07/2013 page20)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|