Pumping up power of consumption

Updated: 2013-06-20 07:26

By Andrew Moody and Lyu Chang in Beijing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Top economist sounds alert on overspending, report Andrew Moody and Lyu Chang in Beijing.

Does China need to consume more?

Despite the Chinese being famous across the world for snapping up luxury goods, household consumption as a share of GDP was 37.7 percent in 2011, according to the latest World Bank figures.

That is far below the 65 to 75 percent in European countries and the United States.

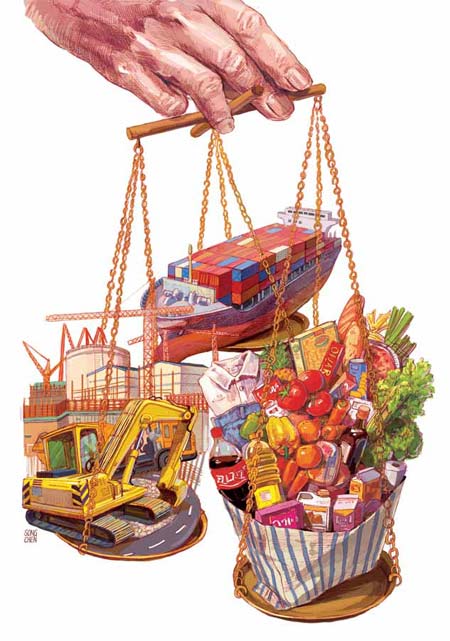

Transforming the economic model, from one driven by exports to one where domestic consumption is key, is a central aim of the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15).

Premier Li Keqiang declared this a central goal at a forum in Beijing in March. "China will expand its opening-up policy and the nation needs to promote domestic consumption by continuing to open up its markets," he said.

There have been fears that relying on investment - particularly after the 2008 global financial crisis and the government's 4 trillion yuan ($670 billion) stimulus package - could lead to a future investment bust, as happened in Japan two decades ago.

Therefore, it came as a surprise when one of China's most prominent and respected economists, Justin Yifu Lin, former chief economist at the World Bank, warned recently that China risked potential disaster if it makes a dash for consumption.

"Those who advocate that China's economy should rely on consumption are, in fact, pushing the country into a crisis. I've never seen any country fall into a crisis because of over-investment," he said.

Renewed debate

Lin's remarks prompted renewed debate about China's economic model and whether it is too reliant on fixed-asset investment and exports, so China Daily spoke to eight prominent economists and experts on China to discover if the preoccupation with driving up consumption levels has been overplayed.

Donna H. J. Kwok, Greater China economist for HSBC in Hong Kong, said the risks are far greater if China retains its current model without adopting measures to encourage consumption.

"The risks posed to China's long-term economic health if no measures are adopted to push the country toward a more consumption-driven model far outweigh those posed by the actual adoption of such measures.

"Relative to China's own history and other developed and developing countries across the world, China's private consumption-to-GDP ratio today is low. As such, China needs to, and in fact already has, started to adopt policies to reflate consumption as a key driver of economic growth."

Jian Chang, China economist and a director of Barclays in Hong Kong, said Lin's position is very much a minority view.

"I think the direction he is pointing to is somewhat against where we would like to see China develop and that is to a more market-orientated economy, one less led and directed by the central government.

"The current consumption level in China is lower than in any other developed economy or developing economies at a similar level of living standards."

Louis Kuijs, China economist at Royal Bank of Scotland in Hong Kong, who was a senior economist at the World Bank during Lin's period as chief economist, also said China has to change its growth model.

"I used to have these discussions at the World Bank. China cannot continue to increase its investment-to-GDP ratio. It is just not possible economically.

"I have sympathy with the argument also that it doesn't make sense to hand out credit cards to try to stimulate consumption, but China definitely needs a better-balanced pattern of growth."

However, Lin, who argues that sustainable consumption can only come from investment in upskilling the economy so workers have higher wages to spend, has his defenders.

Zhu Tian, professor of economics at China Europe International Business School, or CEIBS, in Shanghai, believes the former World Bank vice-president has made an important contribution to the debate.

"In economic theory there is actually no such thing as consumption-driven growth. No serious academic would ever use the term and you can't find it in any textbook. In theory, low consumption is not a bad but a good thing. When the IMF and the World Bank refer to African and Latin American countries, they are talking about the need for sustained investment growth.

"Most of sub-Saharan Africa is poor, not because they don't know how to consume but because they don't have the production capacity, both human and physical."

Tomas Sedlacek, the leading Czech economist and author of the best-selling book, Economics of Good and Evil, also warned of the dangers of going down the consumption-driven road.

"I actually believe it is fine that GDP is boosted by investment (in infrastructure) and by exports rather than driven by consumption as in China," he says.

He said that if China were to go on a spending spree, like that in the West before the financial crisis, it could end up in a similar mess with lower consumption than now.

"Consumption must not be fueled by credit. Historically, with previous global crises, there was nothing to eat as such after a bad harvest. It was a crisis of insufficient supply. Now in the Western world, there is a crisis of demand. There are enough cars and razor blades, but we don't have sufficient consumers."

Retracing steps

China's consumption hasn't always been low. In the 1950s and 1960s it averaged around 60 percent of GDP, hitting a peak of 71 percent in 1962.

Following reform and opening-up in the late 1970s, the government embarked on a program of unprecedented investment to modernize the economy, resulting in the current economic structure.

There is some evidence of that structure already changing. Domestic consumption was a bigger driver of economic growth than investment in the first quarter of this year, contributing 55.8 percent of the 7.7 percent total, compared with 29.8 percent from capital formation and 14.2 percent from exports.

Kwok at HSBC said the government faces the same risks as the early reform administrations when they attempted to alter the economic structure again toward higher levels of consumption.

"As with any structural reform policy, the risk is if the pace and intensity with which reforms are introduced are inappropriate.

"If too slow, structural adjustment fails to occur. If too fast, then new imbalances could be created in other aspects of the economy."

Hans Hendrischke, professor of Chinese business and management at the University of Sydney Business School, said there is a problem with the consumption debate when it ceases to become one between economists and involves the press and other commentators.

"This is what you have when you have a debate that starts off in strictly economic terms and then becomes translated into those who say we must have more consumption because we are against all these investment people. In reality, it is actually quite complex and the two alternatives - consumption and investment - are not actually mutually exclusive."

One significant argument obsessing many economists is whether China's consumption is weak at all.

Zhu at CEIBS pointed out that between 1990 and 2010 China's consumption grew by 8.6 percent per annum (adjusted for inflation), nearly three times the global average of 3 percent.

"In the US, consumption growth was less than 2 percent during this period and in Europe it was 2 percent. Nobody actually needs consumption. It is an outcome of economic growth and not a reason for it. A family cannot get rich by consuming."

It also seems something of a paradox to talk about a lack of consumption when people see nothing but conspicuous consumption by the Chinese, going around the world buying luxury handbags, vintage wines and art.

"For some it is something of a puzzle but that's because of the sheer size of the Chinese economy and its consumer market," said Chang at Barclays.

"It may only be a small percentage going to places like London and Milan but it is enough to make this big difference."

A number of economists also believe the official figures on Chinese consumption may underestimate spending.

These figures are based on household surveys, where a sample of the population completes questionnaires on their consumption patterns.

Zhu at CEIBS said they are weighted to the poorest sections of society who are keen to pick up the small payment made for completing the survey. He estimates that consumption in China could be between 60 and 65 percent, not far below Western levels.

"Poor people appreciate the (financial) compensation they receive for filling in the survey. As for rich people, they might be concerned that some of their income is not so legitimate," he said.

The government has so far attempted to boost consumption by focusing on education and welfare, particularly a universal pensions system, which have been the traditional barriers to consumption, forcing people to save.

It has also increased the minimum wage across the country. Future reforms across the banking system are also likely to make consumer credit more widely available.

The government would also like to see migrant workers settle in new cities with their families as part of the country's urbanization program. They are then likely to spend more, rather than remitting nearly all their wages to families in their hometowns and villages.

Kuijs at Royal Bank of Scotland believes the government has put in place many of the right measures to boost consumption.

"Since 2005, the Chinese government under the previous administration - which is sometimes criticized for the pace of its reforms - has done an impressive job in putting in place many of the measures necessary."

Chang at Barclays said there is no need for the government to "drop money from a helicopter" to boost consumption by such measures as tax cuts or creating the conditions for a credit boom.

"Maybe in a crisis period like a recession, you might need some emergency kind of tool, but what China needs is some deepening of the so-called structural reforms. It also needs to focus on income distribution and improving the social safety net."

She believes that Chinese people will naturally consume more when they reach a higher average income level, particularly on service goods in such areas as recreation, tourism and cultural pursuits.

Younger spenders

The Barclays economist also said younger Chinese already show a higher propensity to consume than their parents and this trend will raise consumption levels over time.

"When I take the high-speed train from Shanghai to Beijing, I often see younger people in first class. The younger generations, born in the 1980s and 1990s, want the best things now."

Zhu at CEIBS argued that it is important for China to get the balance right and have a level of consumption appropriate to its stage of development to avoid the problems faced by other developing countries such as Brazil.

"Brazil has a consumption-to-GDP ratio of around 80 percent, similar to a European country, but the problem is that it is not sustainable, and they are becoming indebted."

He said that the experiences of Singapore proves that to have fast consumption growth a country does not have to have a high consumption-to-GDP ratio, since Singapore's stands at around 50 percent.

"Singapore's annual consumption is growing faster than that of Japan, where consumption is 80 percent of GDP, and that's because it has a higher growth rate than Japan which therefore drives consumption," he said.

Kuijs at Royal Bank of Scotland does not believe that Singapore is a good role model for China, since the city-state is not really comparable with the world's second-largest economy.

"Singapore is a bit like London in that it has a lot of foreign company headquarters and a big professional population that is very rich. It is not an example China can really follow."

Junheng Li, founder of the New York-based equity analyst J.L. Warren Capital, and author of the recently published Tiger Woman on Wall Street - Winning Strategy from Shanghai to New York, said it is not that China has to stop investing and start consuming but about achieving greater balance.

"Investment versus consumption-led growth should not be treated as a binary, all-or-nothing thing, but as a matter of proportion.

"At this moment, domestic consumption is certainly too low but there are issues too about the quality of investment. Much of it is wasted, with too much directed to State-owned enterprises and not enough to the true private sector. The Chinese economy has become increasingly inefficient."

Michael Spence, a Nobel prize winner and now professor of economics at the Leonard N. Stern School of Business at New York University, is one who believes Lin is wrong to downplay the importance of domestic consumption.

"The supply-side shifts are important and necessary, but, for China, not sufficient. The demand- and income-side restructuring is also a key component," he says.

He agreed that there should not be major credit expansion to fuel consumption, but higher domestic consumption is a fundamental part of the rebalancing of the economy.

"The demand side is also critical. Without it, the non-tradable sectors (such as professional services and other activities associated with a developed economy) will be slow to develop and that will get in the way of growth."

Kwok at HSBC, however, said the government has a major challenge on its hands to boost domestic consumption, and it will take time.

"It has already started to adopt policies to reflate consumption as a key driver of economic growth. That said, not only will the delivery of any meaningful result likely take at least another five to 10 years - and need at least another Five-Year Plan - but the process has to unfold gradually," she said.

"The criteria that have to be ticked along this process are not ones that can be completed overnight."

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|