'Flash-quitters' quick to make for the door

Updated: 2013-05-10 07:05

By Shi Jing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Teaching college graduates in Shandong province seek employment at a jobs fair hosted especially for them, which offered more than 10,000 posts. Zhang Zhenxiang / for China Daily |

Growing numbers ditch jobs early, reports Shi Jing in Shanghai.

Would you quit your job if the heavens opened and you didn't own an umbrella?

This isn't the opening line of a corny joke or a lame excuse to ask for a day off. It's a genuine question posed to Cherol Cheuk, a manager at human resources provider Hudson Shanghai.

Cheuk said the president of a company she doesn't want to name for reasons of client confidentiality, received a phone call from his assistant one morning. She cited the above excuse as her reason for quitting on only her third day on the job. Both Cheuk, a human resources professional for more than 20 years, and the company president described the move as "ridiculous".

The "no umbrella" story is highly unusual, of course, but young people quitting their jobs very shortly after starting - within three months or even three days - for reasons beyond the comprehension of older workers, is a relatively new phenomenon in China, and has spawned a new term, "flash quit".

After three rounds of interviews, Hu Xiao, a top student at Fudan Journalism School, was offered a position as a marketing trainee with Kimberly Clarke, the global health products provider on the Fortune 500 list of top companies. It's a job most of his peers would move heaven and Earth to get.

The prospects were enticing; although Hu did not divulge a specific figure, he claimed the salary on offer was "way higher than the monthly average of 4,500 yuan ($729) among Fudan graduates".

The daily commute posed few problems. After riding just nine stops on Line 8 of the Shanghai subway, Hu would arrive at his office, located in People's Square, right in the heart of the city. A ride of no more than 30 minutes and with no transitions is a blessing compared with the travails of most cosmopolitan dwellers. However, Hu still found it "a little bit troublesome to travel to and from work every day" because he "lives on the outskirts of the city", although in the eyes of many observers, his residential area is not on the outskirts at all.

Despite all these favorable conditions, 24-year-old Hu quit his job in October, three months after he started.

A failure to adapt

"My mother had anaphylactic shock at the time. I was terrified and at a loss and there was nothing to do but go back home to Kunming (in Yunnan province). I knew I could offer very little help, but I can't afford to lose my mom," he said.

His mother's ill health was the tipping point that prompted Hu to quit his job, but he didn't deny that his inability to adjust to the office atmosphere was another reason he handed in his notice.

"I didn't get on very well with my immediate boss. As I was a new graduate, I didn't adapt very well to the corporate culture there," he admitted.

In the eyes of many alumni and friends, voluntary rejection of the "perfect" job was a fall from grace for Hu. It took him a long time to adjust to a situation he had never experienced before as the top student at his school, the one who received the most job offers.

"But in retrospect, it did me a lot of good. People need setbacks to grow up," he said.

Hu's parents, who are mid-level bank executives, were quite content with his decision. Their only concern was that their son should be content, no matter what career path he chose.

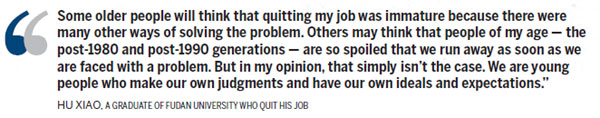

"Some older people will think that quitting my job was immature because there were many other ways of solving the problem. Others may think that people of - my age, the post-1980 and post-1990 generations - are so spoiled that we run away as soon as we are faced with a problem. But in my opinion, that simply isn't the case. We are young people who make our own judgments and have our own ideals and expectations," he said.

"Meanwhile, there are plenty of other opportunities. I have nothing to lose," he added.

'I wasn't happy'

Approximately 57 percent of respondents to a survey on the career adaptability of college graduates changed their job within three years of starting work, while 32 percent had worked for more than three employers, according to a report released by Beijing Municipal Commission of Education in late 2012.

The survey also discovered that the post-1990 generation accounted for the highest number of flash quitters, with 30.6 percent of respondents taking the controversial step, 5 percent higher than the national average.

"I wasn't happy," was the reason Li Yuchen gave four quitting her last job. Although she had been with her employer for almost three months, she had made the decision within four weeks of starting work for the company.

With a bachelor's degree from Nanjing University and a postgraduate degree from the London School of Economics, the 28 year old has had four jobs in her four-year working life.

"It was a global consulting firm and they offered me about 20,000 yuan per month. But I didn't like it, anyway. The management mechanism wasn't transparent," said Li, who now works for an advertising company in Shanghai, earning 8,000 yuan a month.

Her parents are university professors. Neither understood what was happening with their daughter and they never asked.

"I understand that future employers will see frequent job-hopping as a big negative, but, you know, a lot of things in life can't be planned or foreseen," said Li.

Self-fulfillment

Despite this, it would be unfair to assume that young people have no career goals.

In a survey released at the beginning of the year by 51job, China's leading employment website, human resources professionals explained that younger job hunters, especially those born after 1985, are less loyal to their employers because "they are more concerned with self-fulfillment".

Wu Yizhong, 27, spent two months working for a well-known Spanish fast-fashion brand as a supervisor. Wu's degree in administrative management prompted the company to offer her a monthly salary of around 7,000 yuan. Although the remuneration was good, Wu said she could not work with her boss because she felt his management practices lacked consistency.

"What I care about most is teamwork. It matters so much to me that everyone has the same goal. I can't stand it when people reset goals within a very short time period. It means that all the previous efforts are wasted," she said.

She gave herself a month to adjust to the working environment, but when the second month rolled around and she realized she would never embrace the company's ethos and methods, she stopped trying and quit, even though her boss tried to persuade her to stay.

"My parents both work at the hospital. Of course they were worried when they first heard the news. But they are quite open-minded and said they would respect whatever decision I made," said Wu.

Many younger people with college degrees, especially the post-'90 generation, quit because they feel the job fails to match their expectations. At least, that's the experience of Liu Lei, human resources manager at Sensata Technologies of Jiangsu province, which manufactures sensors and control equipment.

"Most of the graduates we recruit have an engineering background. They want to be challenged by their job. If they find the job too easy, with few problems to solve, they will simply quit," said Liu.

"Vocational school graduates are another group prone to flash quitting. If they feel the job is demanding, boring, dull and poorly paid, they stop showing up. But at a company with very strict rules, such as this one, anyone who is absent for three days without good reason will be fired," she said.

High mobility

Meanwhile, it's not just young people from higher academic backgrounds who quit their jobs more frequently than previous generations. Young migrant workers also seem to be adopting a more open attitude toward frequent job changes.

Migrant workers aged 24 or under are now highly mobile, according to a survey conducted by daguu, one of the largest websites providing job information to migrant workers in the weeks following Spring Festival, or Lunar New Year, a traditional time of change.

About 30 percent of the 13,500 respondents said they would not return to the city where they worked before Spring Festival. In addition, 63 percent said they would not return to their pre-holiday employer.

Liu Yiwei works for a government department that helps younger migrant workers find work in Shanghai. In the past three years, she has witnessed an indifference to work and career paths among the young, especially the post-'90 generation.

"Most of the jobs we introduce them to are in the service industry. But they cannot endure the work and quit very quickly, maybe within three to five days. If we ask 20 people to come in for an interview, only 10 of them will actually show up and of those 10, only seven will be recruited. Finally, only three will make it through the probationary period and get the job," she said.

It seems that people are obsessively concerned with "their own age", which may explain why one hears things such as "the post-1980 generation is fallen" or "the post-1990s are decadent".

Zhou Lian, associate professor at the School of Philosophy at Renmin University of China, has examined the reasons behind this apparent fixation.

In his latest book, You Can Never Wake Someone Who Pretends To Be Asleep, Zhou wrote, "The age we live in is especially demanding, because we live in an age where we are so closely related that we cannot be separated for a second. We are loaded down with worries, not because it is the worst of times but because we place all our hopes and despair on the times in which we live."

Cheuk of Hudson has concluded that the same logic should be applied to the jobs market.

"People born in the 1970s used to say that those born in the 1980s are hopeless and now the post-1980 people say those born after 1990 are the 'beat generation'. There is wide discussion on many platforms - Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn - revolving around finding a solution to this frequent, even frantic, job-hopping. Well, it's probably a process whereby employers and younger employees will have to learn to adjust to each other. These times are different; there are so many opportunities outside, after all," she said.

Contact the writer at shijing@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 05/10/2013 page6)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|