Creative cowhide

Updated: 2013-05-13 07:20

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

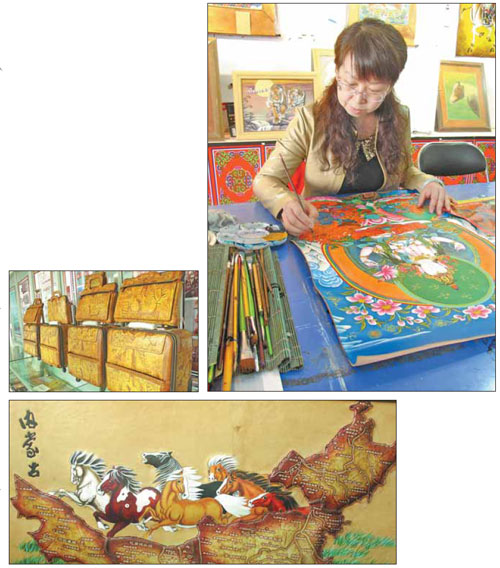

Clockwise from above right: Du Juan works on a cowhide thangka. A leather painting shows running horses and the map of Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Suitcases and bags with leather paintings. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

A studio in Hohhot is hoping to revive the tradition of leather paintings, a unique ancient art form of Inner Mongolia. Wang Kaihao visits the studio to find out more.

Various sizes of wine pots, penholders, and vases stand proudly on the shelves. A huge detailed map of Inner Mongolia autonomous region spreads across the wall. A punching bag containing leather fragments sways in the middle of the room.

These are among the items found in a studio called Suluding, named after an ancient Mongolian spear, located in the autonomous region's capital Hohhot.

At first glance, they may not look special. But with careful observation, visitors will discover that almost everything in Suluding is made of cowhide. And the most precious items in the studio are leather paintings.

At one corner, 37-year-old Dong Jianbin painstakingly polishes a leather painting of horses. The craftsman has been working on it for a few weeks now and says he's giving the painting its final touches.

"Well, I only have to punch holes on the edge of the painting, string hide ropes for decoration, and use another hide to cover its wooden frame," he explains nonchalantly, but to any layperson, the process sounds like a lot of work.

Dong has been in the business since 1998, but he still considers making a leather painting a tough job. For a start, selecting the right material is a major challenge. The surface of cowhide cannot have the slightest damage. The leather must be glossy, soft and of high tenacity.

"Each hide is unique," Dong says. "Depending on each piece's texture, I will need to use different strength to dye the painting and let the colorants filter into the leather at the right rate."

Dong says one will only be able to comprehend the subtleness of coloring after years of practice. To provide texture to the paintings' surface, he goes through an energy-consuming carving process.

Leather paintings were popular among Mongols for centuries. They originated from martial maps during the time of Genghis Khan (1162-1227), and were later used to record scenarios of daily life. But, as it lost practical function in modern times, the aureole of this tradition faded away.

Dong recalls it was difficult to find leather paintings in Hohhot in the 1990s except some small rough pieces in souvenir shops. He was then a designer and disappointed to find some people displaying leather paintings, which were dull in color. So, he gathered a few painters with the hope of creating better leather pictures. He met with more frustrations, having to face an uninterested market.

Their paintings were usually priced at 3,000 yuan ($485) each because of the tedious work involved and the fine materials, but the price was too high for locals whose average monthly income was only in the hundreds during that time. They moved to Beijing with the hope of a more positive response, but sales remained weak. In 2003, he joined Suluding.

"When the SARS scare subsided in 2003, there was an unprecedented golden season for tourism," says 50-year-old Hohhot-native Yun Chengyi of Mongolian ethnic group, who started the studio. "Many people were introduced to Mongolian leather paintings for the first time, and it was a good chance to promote this indigenous culture."

But the road to success has been challenging.

"The general public considers paintings on paper as fine arts, and treats our painters as folk artisans," he says, adding that he felt unfairly treated. "Cowhide was the paper during ancient times for people living on the grasslands."

Yun expresses his regrets for not bidding leather painting skill as an intangible cultural heritage item earlier but has applied recently to the local government, while he opines that it is also important to make sure the paintings leave the shelves of the studios.

"It is not right that only a few people are dedicated to preserving traditional culture behind closed doors," he says. "We must let the public know what we are protecting."

While selling leather paintings in Inner Mongolia, Yun confesses many people doubted the purity of the art, especially when he introduced modern machines and used metallic molds to produce decoration paintings. His sales volume has reached 10 million yuan a year, with 80 percent coming from his assembly lines in another 4,000-square-meter workshop.

Despite the challenges, Dong is pleased that more people have understood the value of the work and are willing to pay tens of thousands of yuan to buy a fine leather picture, while a small decoration painting produced by machine is sold at 100 to 200 yuan.

Yun adds preserving traditional arts and commercialization can coexist without contradiction.

"Traditions will easily disappear if they are not useful to modern people. Leather paintings originated from the daily life of ancient times, and they should continue to be in the lives of people again."

Yun says there are now more than 20 leather painting studios in Hohhot. Suluding, being the largest one, was listed as one of the autonomous region's 32 examples of cultural industry in 2012.

There are about 30 painters in Suluding, but in the recent years there hasn't been any new recruit. Some left the studio for better paying jobs.

Because of the lack of new blood, the paintings are limited to certain traditional themes. They include herding life on grasslands, Mongolian historic figures, and the legendary Wang Zhaojun, who married Huns' ruler in exchange for friendly relations with the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) and was later buried in Hohhot.

But some painters are exploring new themes. Du Juan, a 38-year-old painter has recently tried drawing thangka on leather to reflect Inner Mongolia's rich Tibetan Buddhism traditions. Dong has also experimented combining leather painting with Western oil painting styles.

"We will learn from the fashion industry to sign on contract designers to create more images that are suitable to be drawn on leather," Yun shares his vision. "There will also be more customized paintings. Maybe we can draw your photos on leather."

His ambitious dream also forces Yun to think more seriously about intellectual property rights.

"We can't revive leather painting through our own limited efforts. So, counterfeits are in someway considered a flattery. But, I will not hesitate to file lawsuits if the copycats are too reckless," Yun says with a smile.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 05/13/2013 page22)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|