Country living far from an easy stroll for nation's elderly

Updated: 2013-05-23 07:49

By Zhang Yuchen (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Shi Fuzhu and his wife Xie Taohua replace a damaged light at their home in Chongan village in Ningxia. All their three children work in big cities and rarely return home. Peng Zhaozhi / Xinhua |

Zhang Yuchen reports on the grim plight that faces 'left-behind seniors'.

Cheng Deguang often spends half his day sitting on the banks of the river that connects his village to the city of Jinan in Shandong province. Sometimes, Cheng stares at the water for hours, immobile as a statue. When the temperature begins to fall, he moves inside his house about 1 km from the riverbank.

The 82-year-old farmer and his wife, 72, live on a small piece of land in Huaerzhuang, a village close to the banks of the Yellow River. He can usually count on seeing his oldest son at least once a year, but his younger boy, who works in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, has not returned home for several years.

Although Cheng misses his sons and worries about their lives, his greatest concern these days is the safety of his wife and himself. Last winter, when Cheng was out selling peanuts he had harvested, his wife fell as she attempted to collect firewood near the riverbank.

The mishap occurred in the evening when most people had headed home for supper. With no one to lean on, Cheng's wife stumbled step by step to their house. The pain in her swollen ankle lasted until dawn next day.

Although the incident had no long-term ramifications, and could have happened to almost anyone, it highlights the plight of elderly people living in rural areas.

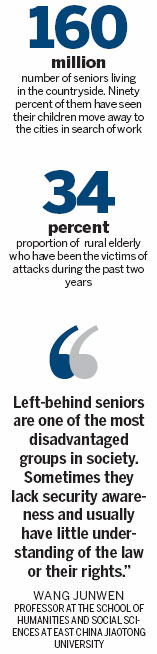

More than 160 million seniors live in the countryside and 90 percent of them have seen their children move to the big cities in search of work.

Of those 160 million, 34 percent have been the victims of attacks or have had accidents, large or small, during the past two years, according to a provincial aging bureau in Shaanxi province.

A sense of foreboding also hangs over the elderly rural poor. Last month, seven seniors were murdered within the space of two weeks in the backwoods of Shaanxi province. Some experts saw the tragedy as a warning of the serious security issues facing elderly people left to fend for themselves in the countryside.

In early April, Chen Jun, a 20-something who had just been released from prison, arrived at Heigou village in mountainous Shangnan county, an isolated spot in Shaanxi. Early in the evening, under the pretext of buying sheep, Chen knocked at the door of Sun Kaicheng, a 59-year-old who lived with his wife, 49.

Starved of company, having not seen their adult children for some time and with the nearest neighbor's house 50 meters away, the lonely couple, who apparently saw no reason to doubt Chen's story, cooked a large meal and invited him to eat with them.

Sun and his wife were robbed and murdered later that same evening, but their bodies went undiscovered for a day and a half. Sun's niece, Sun Rong, who also lives in the county received a call and rushed to her home village, where she discovered that her parents-in-law had also been murdered, according to Huashang, a local daily newspaper in Xi'an, the capital of Shaanxi province.

When Chen was apprehended, he confessed that he had killed the four seniors on the same day. He also admitted killing the three other elderly residents in a nearby village a week or so earlier.

Very few young people live in Heigou village, the population of which mainly consists of seniors and infants. The young have moved away in search of work and few of them can afford to provide food and lodging for their elderly parents in their adopted home towns, while the older children live in the local town where they attend school. That means approximately 30 households in the village consist exclusively of seniors, according to the village leader Weng Liancheng.

The case has highlighted the reality of life for "left-behind seniors" - a phrase used to describe rural dwellers aged around 60 or older, whose children have moved to the urban areas - many of whom live alone, eat alone and rarely receive phone calls or messages from their departed offspring.

Some have no idea where their children are. For example, Cheng Deguang, 80, only knows that his two sons are still alive. "They have their own lives and the burden has already been so heavy for them," he said. "I don't expect them to do more for me."

His younger son has not been home for spring festival for some years. Cheng's voice softened slightly on the other end of phone when he spoke about the boy, but still supports the idea that young people should go out to live their own lives.

Rural versus urban

There is an obvious disparity between the elderly in urban and rural areas. Those dwelling in urban areas can usually rely on their children for support, both in terms of finances and accommodation. The rural elderly are often not so fortunate. Some receive financial help from their children, but despite recent improvements in the social support system, some are struggling and live close to the poverty line, barely able to survive on an annual income of 2,300 yuan ($374).

"Left-behind seniors are one of the most disadvantaged groups in society. Sometimes they lack security awareness and usually have little understanding of the law or their rights," said Wang Junwen, a professor at the school of humanities and social sciences at East China Jiaotong University.

The left-behind seniors are usually poorly educated and reliant on handouts from their children. Moreover, the age demographic in many villages resembles an inverted pyramid, whereby the oldest residents are in the majority, according to Wang.

"Older people in the villages often have to face life's daily difficulties with little or no support. That is the key issue we should address," said Shi Renbing, a professor at Huazhong University of Science and Technology, who specializes in rural demographics.

"The rural culture needs to be rebuilt to foster a return to the traditional countryside culture, such as close family ties and traditional value systems, to strengthen the moral code and behavior patterns," said Wang.

A rising divorce rate, a rural welfare system still under construction and a rising dropout rate at primary and middle schools mean security is only one factor in the lives of the rural elderly. For example, 92 percent of elderly men dwelling in the countryside have to work in the fields to support themselves, even well into later life.

One solution may be the greater involvement of younger returnees, who, although getting on in years themselves, are still appreciably younger than many of their fellow residents and can offer a helping hand.

Warning systems

Meanwhile, local governments now seem to be responding, at least on the issue of security. Following the murders in Shangnan, the county government provided funding to enable isolated villages, where there are often large distances between the houses, to install warning sirens. When a siren is activated, a red light begins to flash, alerting those within a radius of several hundred meters of a possible threat to residents.

In addition, every elderly person in Heigou village has taken advantage of a registration scheme provided by local police, so their safety can be monitored and identification made easier in the event of accident or worse.

In addition, villages with a large number of left-behind seniors can help themselves. The "younger" villagers have been urged to organize patrols to identify problems and keep an eye on any strangers, who are easy to spot in rural communities where everybody knows everybody else, even if only by sight.

The children who have left to work in cities can also play a larger role in the lives of their elderly parents, according to Shi, who said that the young need to realize that simply sending money home is not enough. The young should maintain better contact with villagers to help monitor conditions and not just rely on the assurances provided by their uncomplaining parents.

One solution would be to introduce a number of support facilities to improve the quality of life and help the elderly to enjoy the time remaining to them. "Even though urbanization means rural depopulation, it does not necessarily mean that we should sacrifice the happiness of any particular group," said Wang Junwen.

Sitting on his riverbank, Cheng Deguang said he knows it would be unrealistic to expect to have his children around him, but the help he receives from neighbors is crucial and appreciated.

"Sometimes the younger villagers help me to carry the seeds and fertilizers I use for work on the land. They are really very helpful, almost like a family," he said.

Contact the writer at zhangyuchen@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 05/23/2013 page8)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|