Legacy of a railroad

Updated: 2013-05-27 13:49

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

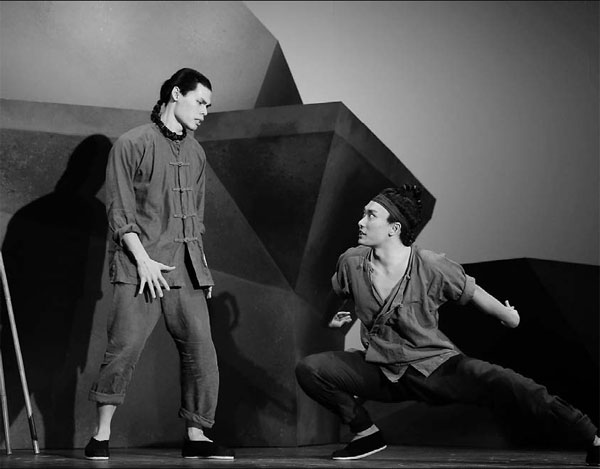

The Dance and the Railroad features two characters, Lone and Ma, Chinese laborers who built the Transcontinental Railroad in the US in the 19th century. |

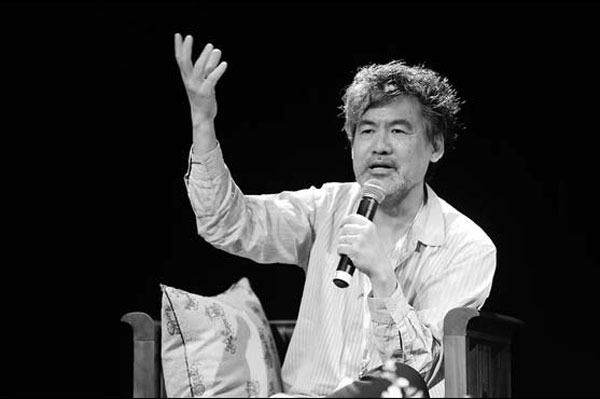

Prominent Chinese-American playwright David Henry Hwang makes his long-overdue debut in the Chinese mainland, presenting a snippet of immigrant history and a theme ready to resonate with an increasingly mobile population, writes Raymond Zhou.

David Henry Hwang was reticent about his expectations for his first outing in the Chinese mainland - for his plays, that is. The debut of The Dance and the Railroad at Wuzhen Theater Festival, which ran May 9-19, arrived with little fanfare, but theater professionals were reminded that the first Chinese-American winner of a Tony Award had actually never seen any of his works produced in a mainland venue - until now.

Set in 1867 when Chinese laborers were building the Transcontinental Railroad, the play features two characters on a California mountaintop. The elder one, Lone, practices his Chinese opera routine while the younger one, Ma, implores him to teach the skills for the role of Gwan Gung (or Guan Gong in standard pinyin). The two are opposites in more ways than age discrepancy. Ma starts as an optimist about the prospect of making money in the new world; Lone is not. Lone despises his co-workers, calling them "dead"; Ma tries to convince him to join them. Their attitudes towards the strike happening in the background are totally different, and that difference is reversed by the end of the play, with the younger Ma more cynical and the erstwhile cynical Lone more accepting of the resolution.

Hwang reveals that the strike as a plot element was inspired by a 1968 student strike at San Francisco State University to call for Asian-American studies, and some of the source materials came from projects that later evolved into New York's Museum of Chinese in America and the Asian-American Studies Department of the University of California at Los Angeles.

The Dance and the Railroad, Hwang's second play, premiered in 1981. For the revival, he incorporated research and discoveries made in the past 30 years. The shortening of the daily work hours from 10 to 8, as mentioned in the original version, turned out to be "not true". The subsequent raise of weekly wage by $5, which is still a crucial piece of information in the current version, was "not related to the strike" as the owners of the railroad insisted.

Hwang considers himself "part of the movement of the American culture of 1970s through 1990s" that is popularly known as "multiculturalism". He started his career with the "Trilogy of Chinese America" plays that depict the immigrant experience at various stages and facets. His mentor, Sam Shepard, encouraged him to "write for the subconscious and the unconscious", and immigration and assimilation as subject matters came naturally.

At a forum of the Wuzhen Theater Festival, Hwang answered questions from the audience about whether his focus on Asian America helped perpetrate a stereotype. He acknowledged that he is familiar with this kind of criticism. "One person or a handful of people cannot represent a whole race, ethnicity or community," he emphasizes. "Only a rich diversity of writers can reflect the diversity of the society at large."

It used to be only Caucasian writers could get into the mainstream, but nowadays ethnic writers, especially the young generation, may no longer be constrained by their ethnicities. Instead of a "Chinese-American writer", one may be called an "avant-garde writer" by the press. "Everybody gets labeled now," Hwang laughs, but the label may not be one's ethnicity any more.

Hwang is acutely aware of the history of Asian-Americans' arduous rise on the theater stage and the resurfacing of the "yellow-face" phenomenon, that is, white actors taking on the roles of Asians. The 1958 staging of Flower Drum Song was the first time Asian-American actors appeared prominently on Broadway. When Jonathan Pryce rejoined the cast of Miss Saigon when it moved from London to New York in 1991, Hwang was one of many Asian-American artists who protested against the casting - for a role specified as Eurasian nonetheless.

"Artistic freedom is important," Hwang says. "People should be able to cast whoever they like. Likewise, people should also be able to express their feelings against such casting if they want to." He notes that a 2012 Royal Shakespeare Company production of The Orphan of Zhao cast only three East Asians, and those in somewhat degrading roles.

Ironically, a yellow face is hardly the kind of topic that provokes those inside China, who are so accustomed to Chinese actors dying their hair yellow and wearing fake noses to play Caucasian roles on stage that they would not raise an eyebrow but may burst into laughter when the makeup and mannerisms are so obviously non-Asian as to appear ludicrous. The concern of many Chinese is the lack of visibility of Asians in Hollywood blockbusters and the recent appearances of Chinese superstars in insultingly short roles.

As China takes a more central role on the global stage, China-related stories emerge with more frequency in the cultural landscape of Western countries. "There are some 30-40 Monkey King stories in production," he illustrates. Audience attitudes have also changed, notes Hwang, from curiosity to all kinds of reactions.

Hwang himself is developing a project based on the legendary kung fu master Bruce Lee, whom he views as "the first popular manifestation of new China". Hwang started that in the mid-1990s, but "just couldn't get the tone right." Two years ago, he settled on a play with dance but no songs. "Every time we made Bruce Lee sing, it came out sounding like South Park." Now, the "dancical" (in contrast to "musical") that incorporates martial-arts movements is set to open in New York at the beginning of 2014.

Hwang cautions that, despite his success on Broadway, especially for M Butterfly, "Broadway represents a tiny slice of American theater," and much of the country's theatrical excellence never heads for the Great White Way, for one reason or another. But he is very much resolved about the so-called conflicts between "universality" and "specificity". "A work becomes more universal by being more specific," he says.

This may be true, but a Chinese-American playwright, as an ethnic minority, is often judged by what he writes about rather than how he writes about it. If he settles for an ethnic story, he can be praised for promoting ethnic culture or lambasted for exploiting exoticness. If he chooses a non-ethnicity-specific story, he could be derided for forgetting his roots or lauded for attempting to break into the mainstream. In China, writers stand out more for their hometowns than for their ethnicities. People hardly noticed that Lao She was Manchurian and Shen Congwen an ethnic Miao, but we all know one created great stories set in old Beijing and the other posthumously turned the border town of Fenghuang (bordering Hunan and Guizhou provinces) into a wildly popular tourist destination.

Indeed, exoticness alone won't carry an artistic work very far. Beneath the glitz and mystique of Peking Opera and diplomatic life, M Butterfly espouses the politics of race and sex, which is universal. The two-hander Dance and the Railroad has at its core the dynamics of mind control. It is about the crossing of paths that many experience in less outlandish settings. I have encountered China's own migrant workers in places like Guangzhou and Beijing having similar generational clashes over an assortment of issues, including the prospect of staying on as urbanites.

What appears as exotic in the US, such as the operatic physical flourishes, merges into the cultural background once viewed in China, revealing the deeper essence of Hwang's play, which, as I interpret it, is conflicting attitudes when one is displaced from one's roots and is faced with an unknown future. You don't have to be a Chinese or an American to identify with that.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

David Henry Hwang talks about his play, which centers on the lives of Asian-Americans, at the Wuzhen Theater Festival in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province. Li Yan / For China Daily |

(China Daily USA 05/25/2013 page10)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|