No longer at home in their hometowns

Updated: 2013-05-30 08:07

By He Dan and Xiang Mingchao in Xinyang, Henan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

A pupil at Wenxing School in Gushi county, Henan province, eats dinner. The school only accepts the children of migrant workers. Photos by Xiang Mingchao / China Daily |

|

Wang Tingting, 16, from Quanhe No 1 Middle School, prepares for a lesson. Wang lives with her 15-year-old brother while their parents work in Zhejiang province. |

Left-behind children make do without their parents

Gao Lili rarely goes home anymore. In fact, she rarely even refers to it as "home".

For the past three years, the 17-year-old has been the only person living in the shabby, two-story village house her parents own in Henan province.

"It's so deserted here," said Gao, explaining that only two other households - a couple in their 80s and a 73-year-old bachelor - still remain. Everyone else has gone, some temporarily for work, some for good.

This scene is fairly typical for a village in Gushi, a poor agricultural county. Its once-abundant labor force left for large cities when the wave of urbanization started in the 1990s. Roughly a third of its 1.7 million residents are now migrant workers.

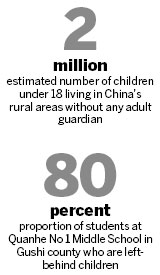

As a result, the county is home to 186,000 "left-behind children" under the age of 18, with either one or, in most cases, both parents working away from home. They account for half of all students in grades one to nine, according to research by the county branch of the All-China Women's Federation.

Gao was born in Qingdao, a developed coastal city in Shandong province, where her parents worked. She was sent home to the family's native Gushi to start school 10 years ago, along with her sister, who was 14 at the time.

Without hukou, or permanent residency, in the city in which they live, migrant workers must send their children home to take advantage of China's free nine-year compulsory education. Otherwise they need to pay high fees to a nearby private school.

Gao's parents both worked on construction sites and originally asked a neighbor in the village to take care of the two girls. Soon after, however, her mother was diagnosed with uremia and returned from Qingdao. She died in the summer of 2009, with the family steeped in massive debts from hospital treatment.

To help pay the bills, Gao's older sister dropped out of school and went in search of employment.

"All of a sudden, I was completely alone," Gao recalled. "It was hard for me to adapt. I was overwhelmed by sadness after losing my mother, and I couldn't sleep at night because I felt scared."

She said she prefers to stay in her school's dormitory than travel the two hours it takes to get to her village, even on weekends and holidays.

Living alone

When it comes to statistics, Gao is far from alone.

In May the All-China Women's Federation released a study - based on data from the 2010 census - that showed China has more than 61 million left-behind children under 18, about 38 percent of all minors in rural areas. The figure represents an increase of 2.4 million since 2005.

Arguably more worrying, the foundation estimated that 2 million of these children live alone without any adult guardian.

A survey of 1.26 million children left behind in rural areas found the older the child, the bigger the chance they live alone. Of those aged 15 to 17, about 6 percent are entirely self-sufficient, the foundation report said.

Wang Tingting, 16, lives in Gushi county with only her younger brother for company. Their parents work in Zhejiang province.

"We used to live with our grandmother in the village, but after we started middle school two years ago it became too far to travel," Wang said, explaining how the siblings came to share a two-bedroom apartment their parents bought near the campus. "She couldn't move with us because she had to feed her cattle and grow wheat," she said.

Wang and her brother receive a weekly allowance of 60 yuan ($10) from their grandmother, but she said her brother has sometimes spent all the money by midweek, leaving them without enough for meals.

Wang Binglin, 36, the sibling's father, later said in a phone interview that leaving his children alone in his hometown was "the only way".

"We're away so that we can provide a better life for our children, as growing crops can't guarantee that," said the decorator, who lives in Hangzhou with his wife, who works at a garment factory.

"We gave up the idea of bringing the children with us, because if we did all our earnings would be spent on fees to enroll them in school," he said.

The first concern many people will have about children being left home alone is safety, with youngsters vulnerable to accidents and criminals.

Gao said her home was broken into and ransacked while she was out, leaving a mass of broken furniture.

"My neighbor, who helps look after the house, told me about it, but I didn't call the police because these things happen a lot in villages," she said. "Besides, the thief took nothing because we have nothing of great value."

Children left home alone also face more long-term side effects, according to teachers and psychologists.

Gao, for example, is an academic achiever and ranks in the top 10 in her class. The principal at her school assures her she will have no problem getting into a key senior high school. Yet she is considering not going to college, as she has heard it costs at least 100,000 yuan for four years of undergraduate study.

"My dad is 60 now, and his health is ruined after years of hard work," she said. "I don't want to let him sacrifice too much."

For Wang Tingting and her brother, who are in the same class at Quanhe No 1 Middle School, their education may end even sooner. Li Li, a teacher at the school, said the duo show little interest in studying and are rarely punctual for class.

"Wang Tingting has even talked about dropping out," he said. "Since they are both going through puberty, I often see big emotional ups and downs."

Principal Wang Yingjun said about 80 percent of his students are left-behind children, and he warned that the absence of a parental figure creates problems for a child's growth.

Many become addicted to surfing the Internet on smartphones, he said, adding that while boys squander money on cigarettes and alcohol, girls are spending their allowance on junk food or make-up.

"School, parents and the surrounding environment are the three vital ingredients to a child's development," the principal said. "If parents are missing, teachers and school administrators bear more responsibility.

"Teachers now not only need to take care of education but also a students' living conditions and psychological state. That's too much to handle."

Tian Guoxiu, deputy dean of the Capital Normal University's Political Science and Law College and a specialist in child psychology, agreed. She said left-behind children who live without parents can easily feel neglected and suffer self-doubt.

"They will think that they were left behind because they are not important, and gradually they will struggle with confidence and lack a sense of security," she said. "All they have is an empty house, so they can also become silent and unsociable."

Although some people may sympathize with the difficulties migrant workers face in raising children in a city without a hukou, Sun Yunxiao is not one of them. The deputy director of the China Youth and Children Research Center said letting minors live alone is "dangerous and unacceptable" under any circumstances.

"The rules on guardianship for children are just useless words on paper if they are not enforced," he said.

Legal interpretation

The Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency, introduced in 1999, states parents or other legal guardians should not let minors aged 16 or younger live alone, while the Law on the Protection of Minors, effective since 2007, warns that parents who cannot fulfill their responsibilities should appoint a temporary guardian.

However, there is no legal interpretation about the punishment for those who break the law, experts say.

"Most migrant workers are from less developed areas, so the government needs to look at increasing investment and policies to boost the economy and create more jobs in the provinces that provide that labor force," Tian said.

Plus, authorities need to remove the barriers that prevent children of migrant workers from receiving an equal education in cities, she added.

Contact the writers at hedan@chinadaily.com.cn and xiangmingchao@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily USA 05/30/2013 page5)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|