Benefits of banking in the shadows

Updated: 2013-06-11 14:19

By Jason Bedford (China Daily)

|

||||||||

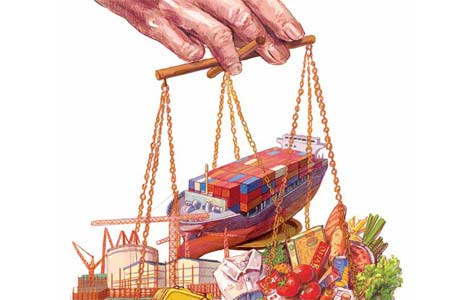

There is nothing to be feared in having a well-managed parallel lending sector

Despite the mixed headlines shadow banking generates, it plays a significant role in the sustainable growth of China's economy.

When the country's shadow banking is discussed it is most commonly equated with trusts, which had total assets under management of 7.5 trillion yuan ($1.2 trillion; 952 billion euros) at the end of last year, but estimates of the size of the shadow banking sector vary widely, ranging from 14 trillion yuan to 30 trillion yuan.

The huge disparity is due to the lack of a firm consensus on what constitutes shadow banking. The narrowest definition encompasses opaque, untracked financing flows, such as underground banking and lending clubs. A more firmly established definition is that of the Financial Stability Board, based in Basel, Switzerland, which refers to "the network of financial intermediaries that conduct maturity, credit, and liquidity transformation without being subject to banking regulation and do not have formal access to central bank liquidity or public sector credit guarantees".

According to the definition by the China Banking Regulatory Commission, shadow banking would be limited to underground banking, entrusted lending by banks, lending by non-CBRC regulated entities and some bank-sold wealth management products. Nonetheless, most market watchers include activities by non-bank financial institutions when referring to shadow banking in China. These non-bank financial institutions include trust companies, leasing companies, credit guarantee companies, securities house firms, micro finance companies and pawn shops, the first three of which are CBRC-regulated entities. Off-balance sheet lending through wealth management products, entrusted loans (lending between enterprises that is facilitated by a bank or trust company) and informal lending networks are also viewed as shadow banking.

Regardless of what definition you adopt, shadow banking often lends itself to negative connotations. Nonetheless, virtually every country in the world has a shadow banking sector - and the lack of one more often than not equates to a less efficient allocation of capital to finance the economy. So while shadow banking can pose risks to an economy, most clearly illustrated by financial crises in the United States in the 1990s and 2007, it is important to understand that the nature of shadow banking is different in China and is very much aligned to the country's current level of economic development.

For example, shadow banking in the US is much more closely linked to financing activities by the banks themselves, particularly in relation to the development of complex structured products, securitization and collateralized debt obligations. In China, shadow banking occurs largely outside of the banking sector and, in fact, growth of this space is directly correlated to periods of credit tightening by the banks.

The existence of a shadow banking sector is in some ways a key element in the sustainable growth of China's economy because it increases the efficient allocation of capital. China's capital markets are still heavily dominated by bank financing, although the rapid growth of the equity and bond markets in recent years is offsetting this.

Nonetheless, many areas of the economy still struggle to secure finance, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises. While access to bank funding for smaller enterprises has risen dramatically over the past few years, it still remains a challenge, particularly for privately-owned small and medium-sized enterprises.

Still, these companies have managed to overcome this challenge in large part because they were able to access funding through the shadow banking sector. The demand for capital in this space is fierce, which is why growth in non-bank lending has outstripped that of the formal banking sector.

However, this situation is changing. Over the past decade banks have faced a difficult transition from financing state-owned enterprises to financing the private sector, which has grown at breakneck speed and now accounts for more than half the economy. However, a great deal of progress has been made, so much so that the term SME has increasingly been replaced with MSE, or micro and small-sized enterprises, by regulators, indicating that the challenge is moving from medium-sized companies to smaller companies.

According to KPMG's annual Chinese mainland banking surveys from 2010 to 2012, net interest margin variance in the sector increased significantly, indicative of the entrenchment of smaller banks in small and medium-sized financing, in which bank loan rates have reached 15 percent. This has led to bank net interest margins ranging from 2.12 percent to 4.87 percent.

On the liability side, the artificially low deposit rates at banks in China have also given rise to a type of shadow banking as well as in the form of wealth management products. While banks do issue genuine wealth management products, some offering yields of 10 to 15 percent, many of the bank-issued wealth management products are simply a way for banks to compete on deposit rates in a market regulated rate environment that restricts deposit rate competition.

These products are generally low risk in nature and offer deposit competitive rates typically between 4.2 percent and 5 percent. Principal guaranteed products, which account for about a third of wealth management products, are on balance sheet, meaning they cannot be deemed a type of shadow banking activity, and the remainder are off-balance sheet products. Again, as with the non-bank lenders, this type of shadow banking in this case is very much prompted by dynamics peculiar to China's banking sector and the lack of market-determined rates.

By no means is the shadow banking sector in China small, but many market watchers often significantly over-estimate its size. For example, the size of the bank wealth management product market is often exaggerated because analysts include in that calculation equity products, private equity funds and other third-party funds distributed by banks.

However, the most misunderstood institutions are the trust companies. It is a mistake to treat the whole of trust assets under management as shadow banking activity. At their core, trust companies are wealth management institutions with lending capabilities, so only a portion of their assets under management could be deemed shadow banking.

Trust products are divided into three categories: single unit-trust products, combined unit-trust products and property management products, the last of which accounts for less than 6 percent of total trust sector assets under management. Single unit-trust products are normally financial intermediary type products and, by definition, only have one investor. Examples of single unit-trust products would be entrustment of a loan between two parties (for example a manufacturing firm directly extending a loan to one of its suppliers) or the purchase and entrustment of an equity stake in one company by another company.

More topical though is the rapid growth of the combined unit-trust products, which are defined as having more than one investor. These products are the wealth-management offerings of trust companies and, despite accounting for only 26 percent of total assets under management at the end of last year, are the key profit drivers for the sector.

In addition to debt products, the range of products within combined unit-trust products is vast, and covers everything from private-equity funds, funds investing in the appreciation of Chinese tea, Chinese white wine and even capital appreciation of graveyards through to sunshine funds (the public equity fund offerings of trust companies) and commodity funds. So while a great deal of the combined unit-trust products are fixed-income debt products, which are normally loans to a single borrower financed by investors, a vast array of different products is on offer by trust companies that do represent a type of shadow banking activity.

The coming years are likely to see a moderation in the growth of the shadow banking sector driven by non-bank lenders as the banking sector and these institutions come to loggerheads and begin to target the same higher-risk borrowers. However, bank-linked shadow banking activities are likely to increase, particularly with the relaunch of securitization in June last year.

This is not a negative development and it should be encouraged. A well-managed shadow banking sector offers many benefits to developing a growing, diversified economy. Moreover, given the level of oversight the CBRC is exercising over this area, and other areas of shadow banking, it is unlikely to lead to the same type of financial crises that have been seen in other countries.

The author is senior manager, KPMG China. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily USA 06/11/2013 page13)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|