What's Paris doing here?

Updated: 2013-07-26 12:12

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

In the late third century BCE, the first Chinese emperor Qin Shihuangdi celebrated the unification of China by constructing palace replicas from each of the six kingdoms he had conquered. Built to two-thirds scale and situated along the banks of the Wei River, each miniature fortress signified Qin's dominance and symbolic mastery of that culture's history.

That tradition is echoed today in the Chinese phenomenon of "duplitecture," in which large-scale suburban developments have replicated entire European towns, American landmarks and urban architecture on the suburban outskirts of cities, including Shanghai and Beijing.

Visitors to Hangzhou's Venice Water Town can enjoy a gondola tour on man-made canals inspired by Italy's "Floating City". In Beijing, real estate developer Zhang Yuchen spent $50 million replicating the 17th-century French castle Chateau Maisons-Laffitte, utilizing the same building materials and working from more than 10,000 photographs. A real estate project in Huizhou is home to a replica of the Austrian village of Hallstatt.

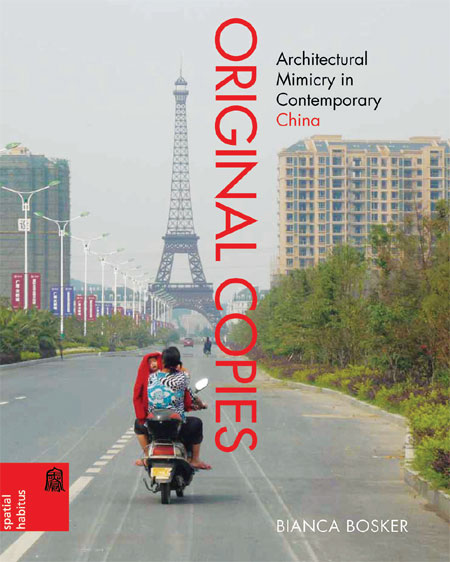

While Western audiences are quick to interpret China's obsession with aggressively copying the best of almost every culture as evidence of a lack of originality, or pure laziness, Bianca Bosker's new book Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China posits that the duplitecture phenomenon reveals otherwise.

China's fixation on replication is a deliberate cultural strategy rooted in a philosophical system that since ancient times has encouraged artists and writers to imitate and improve upon those who have come before, she says. The act is also an assertion of dominance, in a demonstration that another culture's achievements can be easily bested.

"This book proceeds from the paradoxical premise that in the way it copies the West, contemporary China manifests its tremendous originality," Bosker writes.

While Western culture has historically viewed a "copycat" as a thief, Chinese culture has no such tradition, she notes. When Chinese emperors built large garden monuments that paid homage to the gardens and cultures of other civilizations, the implied message was that the creator was powerful enough to literally move mountains and change the ordered world. That context serves as the backdrop against which architectural mimicry now flourishes, Bosker writes.

"Understanding the duplitecture phenomenon takes us directly into both Chinese history and the most pressing issues facing the country today - whether the real estate boom is sustainable, how the growing middle class is spending time and money, and what is driving china's ravenous appetite for copying," Bosker told China Daily.

Particularly noteworthy are the enormous scale and speed at which foreign architectural "simulacrascapes" are being constructed in China, fueled by ample financial resources, cutting-edge technology and a growing middle class that has demonstrated an appetite for Western-style homes. While the Chinese intelligentsia have been quick to denounce the phenomenon as a manifestation of "trash culture", the developments have been extremely popular with the general public, Bosker said.

"There is a huge gulf between the way in which these developments are reviled by architecture critics and intellectuals both in China and the West, and how beloved they are by the people building and living in them," Bosker said. "The families that live in these homes take so much pride in their ability to live in these beautiful Spanish villas, or English country houses. I wanted to understand why Chinese citizens were willing to live out their lives in these replicas, and what that might tell us about the contemporary Chinese dream."

The phenomenon first developed in the early 1990s, made possible by the investment of Taiwan and Hong Kong financiers in Southern China's special economic zones. As construction and development across China has steadily increased - in 2003 alone, the country built 28 billion square feet of new housing - the appetite for Western architecture has only grown, Bosker writes. She cites market research that in 2003 reported 70 percent of developments being built in Beijing at the time featured Western architecture.

For many Chinese, Western-style homes and lifestyles connote status, seizing upon "the iconography of Western architecture as a potent symbol for their ascension - and aspiration for - global supremacy and the middle-class comforts of the 'First World.'"

That wealthy Chinese citizens can indulge fantasies of any life they choose speaks to a new measure of choice for China's most recent generations, Bosker said. In this context, imitating the West isn't a demonstration of self-loathing, or an exaltation of other cultures above China.

"What may seem on the surface as a form of self-colonization or 'West Worship' is actually, to the Chinese, an assertion of China's supremacy," she writes. "They encapsulate a key cultural narrative: they signal China's phenomenal ability to catch up to and surpass the West and to establish itself as a First World power."

Many of these featured developments have been spearheaded by the Chinese government, and the use of Western architecture and building methods is a statement that "what the West can do, China can do too," Bosker said. The fact that most of the Western architecture China has embraced has come from historically powerful countries says much about the impulse that is driving the phenomenon.

In the 19th century, immigrants to the US also duplicated the architecture of England, France and the Roman Empire, but that was driven by a sense of nostalgia and a connection to the cultures from which they drew inspiration. Those buildings also tended to feature architecture that was modern at the time. While China's urban centers have also drawn heavily on cutting-edge Western contemporary architecture, the theme-park showcasing of architecture from eras past in residential developments is unique to China.

Regarding Western critics who have described the entire phenomenon as "terrifying," Bosker says that perhaps the buildings have served their purpose in not only lending credibility to the Chinese establishment among its own citizens, but on the world stage.

"Some people look at this phenomenon and they laugh, but others take note of China's ability to copy as big and bold and as quickly as it does, and there's a certain level of concern," she said. "Personally, I have a great amount of optimism that China's imitation will only lead to innovation in Chinese architecture as it masters the originals."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 07/26/2013 page11)

Top DPRK leader meets Chinese vice-president

Top DPRK leader meets Chinese vice-president

US does not plan decision on Egypt coup

US does not plan decision on Egypt coup

Bo Xilai indicted for corruption

Bo Xilai indicted for corruption

Korean War veterans return to peninsula

Korean War veterans return to peninsula

Tourist safety a priority in S China Sea

Tourist safety a priority in S China Sea

Death toll in Spain train crash rises to 77

Death toll in Spain train crash rises to 77

Royal baby named George Alexander Louis

Royal baby named George Alexander Louis

'The Grandmaster' takes center stage

'The Grandmaster' takes center stage

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Syrian rebels ask Kerry to send US arms quickly

Flights over sea 'routine training'

US does not plan decision on Egypt coup

Congress approves NSA spying program

Japanese PM unlikely to visit Yasukuni Shrine

Girl, 2, thrown to ground; suspect detained

Crackdown a bitter drug to herald changes

Indictment shows CPC's stance

US Weekly

|

|